1-29-17

Asghar Farhadi’s The Salesman:

Linda Loman Is Alive and Well in Tehran

By Diane Sippl

He is a performer, a confidence man who must never lack confidence. His error is to confuse the role he plays with the person he wishes to be. The irony is that he, a salesman, has bought the pitch made to him by his society.

Christopher Bigsby, Introduction to Death of a Salesman

Student: Is it a true story?

Teacher: Not really. But in Saedi’s writing, the atmosphere and character are realistic.

Student: A man turning into a cow! How can you turn into a cow?

Teacher: Gradually…

Asghar Farhadi, The Salesman

What holds (it) together is not this thin narrative thread but the thickening cloud of a fearful, relentlessly worrisome, and inexplicable apprehension that hovers over these characters. There is an inarticulate uneasiness that never dissipates, an anxious concern for something that is never exactly known. The characters are in a constant state of doubt, second thoughts, hallucinations about everything… (a) presentiment of… affliction somehow threatens the entire family with a sinister event that may or may not really happen, though it manages to strain the whole story and generates a collective and sustained state of neurosis… (These) poltergeists regularly trespass into the characters’ otherwise perfectly boring lives.

Hamid Dabashi, Masters and Masterpieces of Iranian Cinema, regarding “Calm in the Presence of Others” by Gholamhossein Saedi in Neurotic Anxieties

Contrary to what the literary canon and the Broadway stage tell us, Death of a Salesman is not the best American play – of the 1940s or the 20th century or any era. It’s not a great play, but it has been translated into many languages and performed around the world, including in Iran, especially if we consider Asghar Farhadi’s recent staging of it for his masterful film, The Salesman, even if, strictly speaking, we see only a few of the play’s scenes there as Arthur Miller wrote them.

Nonetheless, Death of a Salesman made history as an “expressionistic” experiment for which Jo Mielziner created sets and lights that allowed the drama to emerge as a “memory play” in which Willy Loman’s confused present, his fairly distorted recent past, his re-imagined distant past, his long-held dreams, and his puffed-up ego (occasionally pierced by his sons) all crash against each other intermittently within the twenty-four hours that contain this American classic. In other words, this is a play that transpires in time. And here time is fluid: Willy’s mercurial mood can shift instantaneously as he and other characters emerge from the darkness of his mind under the klieg lights or pass through the walls of his home that become porous as time permits, chambers designated mostly by separate horizontal layers on a skeletal scaffold.

For the sake of contrast, we could say that The Salesman is a film that happens in space – or particular spaces: the theater, the classroom, and especially the apartment, both the original one, its window panes imploding before our eyes, its walls so damaged that the tenants are forced to evacuate, and the second one, into which the protagonists (an actor-teacher, Emad, and his actress-wife, Rana) re-locate, and most abruptly, at that, as a temporary solution. It’s a space with cracking plaster, sparking electrical sockets, and dripping ceilings, but it also seems to be haunted by its previous occupant who doesn’t quite depart – at least she doesn’t move her belongings because, she says, her new place doesn’t work out.

This prerogative leaves the new renters in a precarious position, to say the least. Not only is this home a “suspended” space, somewhere between old and new occupants, but it becomes an increasingly uncomfortable habitat as the behavior of the past tenant fuels the neighbors’ gossip. Now realize, this woman is truly a ghost because we never see her, but worse, she (or at least her reputation for receiving too many male guests) hovers over the home of the husband and wife as if an angel of death, not unlike The Woman in Miller’s play who joins Willy in his hotel room. In fact, in the play she slinks out of the bathroom in nothing but a black slip, compromising Willy’s surprise visit from his son; hence the bathroom becomes a key location in the temporary home of Farhadi’s protagonists, as does the staircase (in many of his films) and the concrete jungle surrounding the apartment. Even the basement garage becomes an ominous “cell” or “tomb” where a mysterious truck is held captive and the camera, as in most scenes, is “on guard” as if it were another inhabitant. All of these spaces are both physical and symbolic in a film for which the mise-en-scène unspools the story – or at least, what there is of it.

Compared to some of Farhadi’s other films, such as A Separation (2011) with its linear, twisty, quizzical plot, About Elly (2009) with its lyrical parallel track for the mysterious eponymous character, and Fireworks Wednesday (2006) with its effervescent satire of social stratification and domestic hypocrisy, the storyline of The Salesman (2016) is actually quite simple. Yet there are at least three layers of Death of a Salesman in Farhadi’s film: the one written by Arthur Miller that the theatre group is staging, the one that happens to the cast of the play behind the scenes, and the one that emerges by the end of the film when another character, a salesman, enters the story. But this play-within-a-life-within-a-film is not all. There are also the “blurred” moments – the experiences “between” realities: between the stage and the screen (as at least three females in the film suffer the projection of “The Woman” from the play upon themselves by others), between the play as it is written and as it is performed (when it slides off the rails into desperate improvisation and comes to a crashing halt), and between the actor playing Willy Loman and the real-life salesman, elderly and should-be-retired, who lives the role.

This last distended space sets up a volley between two ways of reading the overall film: as a revenge drama or as a story of lost honor. As Farhadi puts it, the film could be considered “…a social commentary or a moral tale….” Yet there is another way of seeing it all come together, and this is as a critique of sexual politics in Iran today via a transformative rendering of Linda Loman that lifts her from the status of a devout, abject, co-dependent doormat for Willy and his sons to that of a sensitive, vocal, decision-making woman who commands the respect of her actor husband. Ellipses, gaps, and overlaps arouse us via the film’s editing to look for clues and answers, not so much to discover what happens as to note what doesn’t happen, and to see how it all works – theatre, film, life, and all the messiness in-between. How do ego and entitlement adulterate admiration and affection, and how does love sour into contempt?

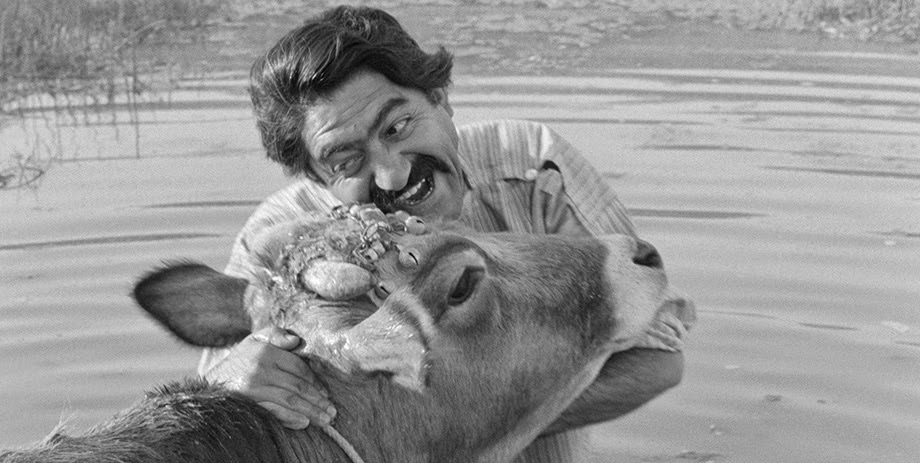

Perhaps, having considered all the rich complexity of The Salesman (which is not yet to have mined it in the least), there is still one more facet to this jewel that glistens, and it may well be the most clairvoyant. However insightfully Farhadi maneuvers between Miller’s play and his own film – between Willy and Emad, between Linda and Rana, between Charlie and Babak, between Biff and Sanam, and between The Woman and Kati, not to mention their off-screen counterpart, the “former” phantom tenant – one more aspect adds light to the entire edifice that Farhadi holds suspended in space and time. That edifice is the old and shaky social construction of gender known as patriarchy, and in The Salesman, Farhadi’s shooting arrow to this house of cards, one that will topple the balance and friction that sustain it, is the short story-turned-film, The Cow, the work by which the prolific Saedi/Mehrjui partnership commenced in Iran. Emad has assigned the story to the all-boy high school class he teaches, and he promises that once they’ve read it, he will show his students the film as a reward.

Dariush Mehrjui directed the film, The Cow (1969) from a script by Gholamhossein Saedi based on Saedi’s short story of the same title in The Mourners of Bayal (1964). Saedi was already by then a renowned dramatist who earned a reputation in Iran for an unprecedented brand of realism that hinged on a nearly clinical psychopathology of the uncanny. His depiction of neurotic anxiety drew from superstition, hallucination, and delusions. At once a writer and a political activist whose career blossomed under Mohammad Mosaddeq in the 1960s, Saedi also earned a doctorate in psychiatry and practiced the profession up until the Islamic Revolution in 1979. Early on he had helped establish the Association of Iranian Writers in order to fight censorship.

In “The Cow,” as throughout Saedi’s output of nearly fifty plays, novels, novellas, short stories, and ethnographies, routine rituals are drained of all meaning, yet a pervasive sense of despair hovers over them. Bayal is a fictitious rural village, deprived and abandoned, yet brimming with fear of known and unknown threats, phantasmagoric nightmares, plagues real and imaginary, and a basic dread of the ordinary, which becomes mysterious when fact and fantasy overlap and merge. In a subsequent short story, “Calm in the Presence of Others,” Saedi shifted this world of looming danger to a middle-class urban environment to present a retired man slowly going mad. Again, every important detail about the man is held back, yet his inexplicable behavior generates a feeling of ritualized terror, an uncanny anxiety.

If we consider the uncanny to be an accidental form of self-exposure, a revelation of what is meant to be private and hidden, we can take it one step further in Saedi and look at the return of the repressed (both in the psychodynamics of the individual and in the politics of a tyrannical society). In “The Cow,” the story of an extremely poor man, Masht Hassan, and his intense love of his animal, when his cow dies, the man, so to speak “ingests” its soul (much the way Emad would take on a role in theatre acting). The man then appears mentally deranged because he feels he is his cow. Yet Saedi is not commenting on this man’s psychotic distortion of reality in Bayal (just as Farhadi here is beyond Emad’s extreme introjection of Willy Loman’s persona), but on the reality the village wants to hide or evade (call it the betrayal, or nature, of the American Dream for Willy and of patriarchy for Emad); Saedi and Mehrjui seek to expose an illusion of reality that is clearly fabricated. To do so, they build the condition of the uncanny within a context of quotidian conformity, opening the door to the return of the repressed. The Salesman does it via Willy’s haunted memory of “The Woman” and Emad’s dark fantasy of the female “ghost” tenant who won’t leave. Both “femme fatales” seem to do remarkable damage, considering they never appear as alive in the setting of the play or the film.

Farhadi renders The Woman in the real-life crisis of Rana and Emad as absent (from the building) but present (as she haunts the building), whereas The Woman as rehearsed by the real-life actress for the play, Kati, comes off as a sad, unintentional parody of Miller’s character as written, in a red trench coat and hat (thanks to the censor’s code) when she’s supposed to be running half-naked from the bathroom, and thus Kati is mocked by her male colleague. In “The Cow,” the Porussis, the menaces from the neighboring village, are looking for the chance to “steal” something from the Bayalis; in The Salesman it would be Willy’s integrity, Babak’s fidelity, or the money the old salesman leaves out for the “phantom” woman’s child. And both “phantom” women, the former tenant and the actress Kati who plays The Woman, are single mothers in life, each trying to raise a son on her own. And both Babak and the real-life elderly salesman appear to be fond of and generous with the former tenant, trying to help her with money and favors. Could it be that in the harshly judgmental community of Teheran – traditional, bigoted, and fearful – Babak’s and the elderly salesman’s taboo behavior is actually a genuinely loving relation with the woman, just as is Masht Hassan’s relation with his cow in Saedi’s story and Mehrjui’s film, where out of the profoundest love, he actually becomes the cow in a Bayal bereft of humanity and feeling?

Then perhaps Rana, Emad’s wife in The Salesman, joins their lonely ranks as the film closes. When Saedi’s Masht Hassan psychotically becomes his deceased cow, in a perversion of the surrounding community’s value system, he turns the cow’s tragic death into a celebration of life. Likewise in Farhadi’s film, Rana exits the tragic death of an elderly salesman with her own self-rescue into a new life. The death is not simply the death of the elderly salesman – is it? Perhaps the real salesman, who finally comes to sell himself ever as much as Willy Loman did, is Emad, the one who dies, symbolically, along with all that propped him up, in a role that now gives up the ghost.

When Rana ultimately defends her “enemy” against Emad’s attack on him, Farhadi suggests that the real enemy is not simply Rana’s attacker but the system that, in an uncanny way, may well now punish Emad, its very emissary. Emad is a progressive Iranian actor playing a liberal American role as a critique of a modernizing society that leaves the “low man” in the dust. In the context of the play, Linda Loman remains a martyr for the dream, but in The Salesman, Rana becomes much more – the vehicle for the return of the repressed in Emad when what has been repressed is not the myth of popularity, success, and class mobility in a developing Iran so much as the myth of male superiority, authority, and ownership – of patriarchy, a construction perhaps older and deeper than the Puritan ethic of capitalism Miller seeks to expose. If Willy’s selfish and clumsy behavior gets him caught in his own lie by his son’s visit, Farhadi, in the footsteps of Saedi and Mehrjui, takes it a notch further: Emad gets caught in a could-be-murder, which is no longer the ordinary predicament of duplicity but, in essence, the extraordinary situation of the uncanny. Emad “goes off the rails,” so to speak, shoring up the very codes of patriarchal entitlement as an age-old construction that the society does all it can to keep under wraps. What is repressed by patriarchs and so-called progressives alike, including “forward-thinking” actors in the cultural sector of the society, is unleashed not so much upon an elderly salesman (the occasion for Emad’s seemingly psychopathic behavior), as upon Emad himself, an actor who is revealed as an uncanny posturer of avant-garde values just as the society is exposed as a screen for moral hypocrisy.

To his credit, Farhadi gives us not an ogre of oppression in Emad, but an earnest husband, teacher, and would-be father who most likely takes on acting as the very step-in-the-right-direction of changing the tyranny of the society, taking for granted the patriarchal order as part and parcel of the regime. In this sense Farhadi shadows his predecessors, Saedi and Mehrjui, in his capacity to see truth through a distorted lens. He posits manly come-uppance as not so much immoral as absurd, alienating it from the logical sequence of events within Teheran’s middle-class neighborhood today – not as evil but as an entire socio-political belief system that Emad (unknowingly) represents.

In this sense Emad, the “low man” (Loman) but good man, the fallible husband, embodies his love-object – we could say Rana, his wife – in a perverse metempsychosis in which her “spirit” (which seems to have left her in the aftermath of her tragedy) is reincarnated in Emad when he introjects what he perceives to be her emotional needs (as if she weren’t capable of possessing and processing them herself) and projects them upon the elderly salesman and his family, as they become Emad’s screen – or stage – for vengeance. So is The Salesman a revenge drama? In any event, it is a film that speaks of lost honor; however, it is Emad, not Rana, who loses the honor – it is the “salesman,” who sells himself.

The Salesman

Director: Asghar Farhadi; Producers: Alexandre Mallet-Guy, Asghar Farhadi; Screenplay: Asghar Farhadi; Cinematographer: Hossein Jafarian; Editor: Hayedeh Safiyari; Sound: in memory of Yadollah Najafi, Hossein Bashash; Music: Sattar Oraki; Art Director: Keyvan Moghadam; Costumes: Sara Samiee; Make-Up: Mehrdad Mirkiani.

Cast: Shahab Hosseini, Taraneh Alidoosti, Babak Karimi, Farid Sajjadi Hosseini, Mina Sadati, Maral Bani Adam, Mehdi Kooshki, Emad Emami, Shirin Aghakashi, Mojtaba Pirzadeh, Sahra Asadollahe, Ehteram Borourmand, Sam Valipour .

Color, 125 min. In Farsi with English subtitles.