3-22-13

A Mind of Her Own: Mrs. Warren’s Profession

By Diane Sippl

Ramón de Ocampo as Frank Gardner, Rebecca Mozo as Vivie Warren

Shaw:

“Dear Mr. Churchill —

Enclosed are two tickets for my opening night, one for you and one for a friend, if you have one.”

Churchill:

“Dear Mr. Shaw —

Unfortunately I cannot attend your opening night. Please send tickets for your second night, if you have one.”

How talky, that man, who never stopped spewing out his ideas through the mouths of actors who sat on a bench, stood by a gate, leaned on a fence, or at best, lit a fine cigar or took a swig of whisky, as Vivie Warren does when she finally settles down for a moment of relief. No tarantellas danced nor doors to the home closed behind nor letters tossed into the fire as in Ibsen, no plays within a play nor gunshots fired as in Chekhov; instead, political stances espoused as in The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism, Capitalism, Sovietism and Fascism. No action. Nothing happens. No one moves. Except that by the final curtain, everything we might have known has changed. Is Shaw didactic? Pedantic? Hardly. Clear-headed, shrewd, witty — yes. A man of words, when “the play’s the thing” because spoken words bring not only knowledge and humor but a humane world. This is the Shaw I know.

And this Shaw, at least in Mrs. Warren’s Profession as presented by the Antaeus Company in North Hollywood, straddles two spheres at once: the broad network of continental Europe — Paris, Brussels, Vienna — where Mrs. Kitty Warren oversees her enterprises, and the quaint cottages and gardens of Haslemere in Surrey, England, where Vivie Warren is receiving her mother’s visit. After an entire childhood and youth of boarding schools, Vivie, a third-year scholar at Cambridge (women weren’t allowed to graduate with a degree) will read law and do actuary calculations with an eye to the stock market. She hates holidays but likes working and getting paid for it, yet thanks to her mother, there’s always been “a good bit of money to make things smooth.” Neither Kitty nor Vivie is a conventional woman in Victorian England, though each will label the other as such, with a good dose of animosity, while they grudgingly work out the proper place of women in the society.

Bill Brochtrup as Mr. Praed, Rebecca Mozo as Vivie Warren

So it’s not just the two women as individuals who are unconventional, but their whole family configuration — that is, until they start talking, or at least until Shaw starts talking, in his most astounding but persuasive way, about the economic and human realities behind the social hypocrisies of all classes in European capitalism. Through Vivie’s confrontations with her mother we learn, little by little, as she peels off the layers of Kitty’s not-so-well-polished veneer, that many families, maybe most, have gone awry of the Queen’s virtues and the hearth’s values in order to survive, each at their own levels.

George Bernard Shaw wrote at least sixty plays, six novels, and countless reviews of music, literature, and theatre as well as political pamphlets and lengthy essays that sometimes served a prefaces to his plays; Mrs. Warren’s Profession was his third play, written in 1893 when he was 37. Owing to its subject matter, it was immediately banned from public production by Britain’s Lord Chamberlain and was not presented on London’s public stages until 1925; it took the upheavals of three decades for people to become more aware of its themes. The attempt to present it to Americans actually came earlier, in 1905, but the New York Police Department literally raided the theater mid-performance and pulled the actors off the stage, citing the entire company for disorderly conduct. Why all the uproar?

Rebecca Mozo as Vivie

Warren, Anne Gee Byrd as Kitty Warren

Each will also consider the other a hypocrite, not that our stage isn’t full of them — starting with Mr. Praed, a genteel fellow who can’t bring it upon himself to speak directly of Mrs. Warren’s true profession with her daughter. Sir George Crofts is more direct: he simply wants Vivie’s hand in marriage, offering his with a handsome bundle of monetary compensation, for Vivie and for his business partner, Mrs. Warren. Never mind that he is twice her age; there is worse to worry about, as Vivie will discover. As in many a Shaw play, a clergyman neighbor is the shadiest fellow: what will the Reverend Samuel Gardner do with that whole box of letters between himself and his one-time liaison, Kitty Warren? The most up-front, yet the dodgiest in terms of a suitable marriage partner for Vivie in her mother’s eyes even though he looks the most compatible, is the Reverend’s son, Frank Gardner. Note that while Frank is the only one of the two who lets on about the matter, it appears that both Gardners have already sown their seeds with the Warrens, age-appropriately. Just the same, Vivie’s father is out of the picture, so it seems, and at least by the end of the play, once Crofts convinces her who has really paid for her college education, Vivie wants neither a husband nor a mother — nor a father.

Bill Brochtrup as Mr. Praed, Ramón de Ocampo as Frank Gardner

John-David Keller as Reverend Samuel Gardner, Ramón de Ocampo as Frank Gardner

There had certainly been plays about prostitutes staged before this (although in England and America, also with their fair share of trouble), yet Shaw ups the anti here. Mrs. Warren has not only worked as a prostitute but also as a madam, and not only as a madam but as a procuress — an entrepreneur of establishments across all of Europe with the “traffic” that was in many ways the most lucrative because it was the most widely supported. That women were punished and scorned for laboring as prostitutes was one thing and Shaw addresses it along with the hypocrisy, but characteristically, he needed to get to the root of it. He tells us he wrote the play

…to draw attention to the truth that prostitution is caused, not by female depravity and male licentiousness, but simply by underpaying, undervaluing and overworking women so shamefully that the very poorest of them are forced to resort to prostitution to keep body and soul together.

It’s difficult not to question his basic premises today with regard to women’s leverage for earning income, waging political power, expressing themselves candidly, and commanding social respect. How all of these challenges

play out between mothers and daughters — across not only generations but sometimes social classes and nationalities or cultures — is another drama: Shaw was ahead of his time in looking not only at the personal psychodynamics in the family but also at the global picture of this unregimented trade in Mrs. Warren’s Profession. How to write astutely from these two seemingly opposite poles?

The relatively young playwright in Shaw let a bit of darkness out in his original version of the play that goes beyond what was generally published thereafter. A keen example is Croft’s exchange with Mrs. Warren in Act I, Scene 2 as Antaeus stages it (or Act II of four in Shaw’s script). Crofts proposes to his partner, Kitty, that if he married Vivie, he’d settle the whole property on her and even hand Kitty her own check on the wedding day. “Why shouldn’t she marry me?” he presses Kitty.

“You!” retorts Kitty in the published edition. And the Antaeus production adds, from Kitty, “How do you know she’s not your daughter?”

“That’s part of the fascination…” replies Crofts. The sexual innuendo, restored to the dialogue by director Robin Larsen upon consultation with dramaturg Christopher Breyer, echoes a gesture moments earlier in that scene when Kitty Warren takes Frank’s flirtatious face into her hands and gives him a full-fledged kiss on the lips.

“There! I shouldn’t have done that. I am wicked,” she states. “Never mind, my dear: it’s only a motherly kiss. Go and make love to Vivie.”

“So I have,” retorts Frank, “Vivie and I are ever such chums.” When Frank claims honorable intentions, she tells him he has a “nice healthy two inches of cheek” all over him. Yet, beside the fact that Frank taunts her (and his father) as if he is well aware of their past, who is it has “cheek” here? Neither Kitty nor Crofts seems to be able to contain their incestuous urges. Such tendencies attracted Shaw’s attention just as prostitution and eugenics did as social and political practices that anchored themselves in family relations.

George Bernard Shaw’s dialogue is already devilishly witty in Mrs. Warren’s Profession, yet the performances in the Antaeus production animate his cerebral play. The most singular impression is the tenderness expressed on the part of both Rebecca Mozo as Vivie and Anne Gee Byrd as Kitty. Shaw’s written play ends with Kitty washing her hands of all the “dirty work” of her mother and Crofts with more or less a sigh of relief. Robin Larsen’s direction has Rebecca Mozo heaving with a momentary anxiety attack, undoing the top of her buttoned-up blouse as she gasps for air. Larsen’s thought is that Kitty has to endure some amount of emotional loss upon getting to know her mother, or worse, getting to know that she will never quite understand or communicate with Kitty Warren as she might once have wanted. The finale belongs to Mozo, as does the play.

Anne Gee Byrd as Kitty Warren, Rebecca Mozo as Vivie Warren

A. Jeffrey Schoenberg’s costumes make just the right statements. Kitty’s red moiré taffeta frock with its ivory voile bodice might seem obviously garish but it works perfectly with Vivie’s peach and russet pinstripe muslin — for is she not a softer version of Kitty and, like-mother-like-daughter, fighting her own way through the given social mire of a world hardly improved since Kitty’s youth? Anne Gee Byrd as Kitty refrains from donning a sizable flowered and feathered hat as Shaw recommends in his stage directions, but (at least at my performance) she struts a coiffed wig of flaming red hair that brings out her rouged cheeks and turquoise-powdered eyelids in true form. Vivie simply wears her dimples, whether she’s puffing out her cheeks in a rare smile or, more often, dropping her jaws in judgment as she purses her lips discerningly. For example, when Crofts presses her with his desire to settle down with a lady Crofts (and that would be Vivie), he reduces her to a nonplus. Her expression transpires with half a dozen variations of dimples, from discovery to shock to dismay. The brown wool vest she wears in her office reminds us of the “manliness” of her pursuits and her style as Victorians perceived her.

Jeremy Pivnick’s lighting is particularly effective. At the end of the first scene, rather than the “fade-to-black” closures of subsequent scenes, a surprise arrives with a brilliant full-stage flash as if the powder strip on an old, large-plate 19th-century camera has gone off. That split second of illumination fixes the actors on the stage, posing in character, for us to contemplate as the lights dim and the same actors rearrange the stage for Scene 2. The flash also reminds us that Shaw was an avid photographer all of his adult life and ardently supported the then new technology as an art form by serving as a critic while he experimented with his own cameras and processing.

François-Pierre Couture’s scenic design is spare and lovely, with airy picket fences and gates that work as subtle conceptual boundaries for the characters yet let the play breathe at the same time. A simple wood slat wall and an ethereal tree lend a wistful feeling to this “unpleasant” play (in Shaw’s terms). We get to peek through the slats in that wall in the final moments of the play as its backlighting discloses the shadowy figure of a young woman — Kitty in her youth, perhaps, in our imaginations, or one of the madam’s cadre who has replaced Vivie as an “adopted” daughter as Mrs. Warren continues to “mother” in her own very professional way.

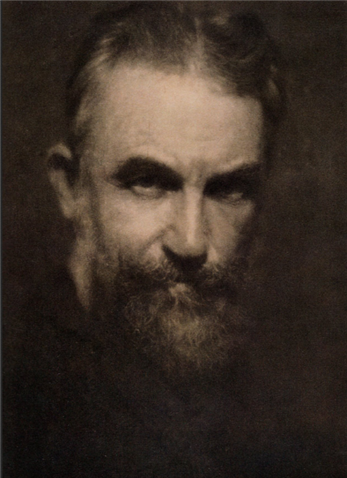

George Bernard Shaw photographed by his friend, Alvin Langdon Coburn, in 1908

In 1891, Shaw’s

groundbreaking essay, The Quintessence of

Ibsenism included a section called “The Two Pioneers”

that pre-figured the heroines in Shaw’s plays just as it painted a portrait of

the Norwegian “founder of modern drama.” Now, some sixty years after

the Irish bard’s long life, we can see it as

Shaw in the mirror. He begins: “That is,

pioneers on the march to the plains of heaven (so to speak)...

The second, whose eyes are in the back of his head, is the man who declares that it is wrong to do something that no one has hitherto seen any harm in.

The first, whose eyes are very long-sighted and in the usual place, is the man who declares that it is right to do something hitherto regarded as infamous.

The second is treated with great respect by the army. They give him testimonials; name him the Good Man; and hate him like the devil.

The first is stoned and shrieked at by the whole army. They call him all manner of opprobrious names; grudge him his bare bread and water; and secretly adore him as their savior from utter despair.”

A mere two years later, Shaw would end Mrs. Warren’s Profession by giving Kitty Warren his characteristic note of irony in her penultimate line: “But Lord help the world if everybody took to doing the right thing!”

Mrs. Warren’s Profession

Playwright: George Bernard Shaw; Director: Robin Larsen; Producers: The Antaeus Company; Scenic Design: François-Pierre Couture; Lighting Design: Jeremy Pivnick; Costume Design: A. Jeffrey Schoenberg; Sound Design: John Zalewski; Dramaturg: Christopher Breyer; Stage Manager: Deirdre Murphy.

Cast: Tony Amendola, Anne Gee Byrd, Daniel Bess, Bill Brochtrup, Ramon de Ocampo, Arye Gross, John-David Keller, Robert Machray, Rebecca Mozo, Linda Park, Kurtwood Smith.

The Antaeus Company, 5112 Lankershim Blvd., North Hollywood, CA 91601

Tickets: (818) 506-1983 or www.Antaeus.org March 14-April 21.