11-22-09

The World Inside La Danse: Wiseman’s Latest Reality Fiction

By Diane Sippl

Isabelle Ciaravola in The Nutcracker

From the grand and stately streets of Paris that deliver us to the front door of the Palais Garnier, we go far below to its dark and seemingly endless catacombs, roaming through them to a room of coiled ropes and pulleys that appear to be part of the stagecraft of the Paris Opera House. Then climbing the stairways of empty halls, we suddenly hear music and the sound of feet landing on floors to the commands of an international coterie of voices: “Head looking there… Plié, hold it — … Bend and show the foot and piqué… Stay in line… Turn the leg out a bit more, no, just a bit … Relevé… Glissade, jeté, now on the floor, plié… You imagine an arabesque and it’s not there!” And then, one soft and meager retort from a rehearsing ballerina, “You blame me too much.”

The last remark is a bit of precious little dissent that will arrive in the next 150 odd minutes of Frederick Wiseman’s latest venture in exposing the institutions of our era, La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet. Like the 37 feature-length documentaries he has already given us since 1967 (which have won ceaseless awards and given rise to 53 retrospectives of his work around the world from 1972 to 2006, with a lengthy one coming up at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art in 2010), La Danse bears the Wiseman ethic and aesthetic of “observational cinema.” That is to say, he uses film (still 16mm, after all these years) to investigate and reveal the structure and function of an organization “in the raw,” so to speak, without the spoon-feeding conventions of the commercial documentary that range from talking heads and voice-over narrators to on-camera interviews and intertitles identifying the speakers and “witnesses.” There are no speeches, no graphics and charts, no found footage or compiled documents, no eye-popping effects or animation sequences — and often, it seems, no linear thread or (real-life) story to follow. What, then, do we have?

The Theater of the Palais Garnier

The Wiseman way is to draw a circle around a particular social space: whatever transpires within it qualifies as possible content for the film, and whatever lies outside will stay there, even if shown minimally to establish the frame of reference. The camera, then, becomes our seeing eye, and we trust it to convey life as it happens, in its own time and rhythms, its unfiltered impact. And what we see might seem real, but obscure or elusive at the same time. For example in La Danse, we see the troupe of the Paris Opera Ballet rehearse and perform parts of seven ballets — Paquita by Pierre Lacotte, The Nutcracker by Rudolf Nureev, Genus by Wayne McGregor, Medea by Angelin Preljocaj, The House of Bernarda Alba by Mats Ek, Romeo and Juliet by Sasha Waltz, and Orpheus and Eurydyce by Pina Bausch — yet we might not be able to tell who is dancing or what is being danced until the end credits. The ability to name it is not the point; the chance to discover and appreciate it is. Regarding dance itself, Wiseman has returned to it after exploring the very different structure and function of the American Ballet Theatre (Ballet, 1995) because he finds the art inherently cinematic:

“Since movies are about movement, I wanted to make a movie about a group of dancers and choreographers who represent the highest level of achievement in the conscious use of the body to express feeling and thought. I have great admiration for the dancers, choreographers, administrators, and technicians of the Paris Opera Ballet and welcomed this opportunity to film them at work.” And their work is exactly what we get — most of the time, the painstaking, repetitive labor of dancers rehearsing with each other and with choreographers and ballet masters who will determine the result.

Marie-Agnès Gillot in Genus

True enough, not only is there

talent on tap, and not only are we ourselves patiently learning to stop, look,

and listen, as we never have before, to exactly how that talent is honed into

the breath-taking beauty of performance, but there is something else at stake,

both within the organization of the ballet company and also between the

filmmaker and us — and that is collaboration.

For though Brigitte Lefèvre, Artistic Director (and administrative

manager) of the Paris Opera Ballet might appear autonomous with her off-handed

airs and fountain of brittle banter (she could talk the stripes off a tiger),

she is no more the troupe’s grand dame than is Frederick Wiseman (or cinematographer John Davey) our purveyor of direct observation of the company's activities. Their roles are both smaller and greater than these.

For example, Brigitte Lefèvre explains in a phone call at the outset of the film a clear notion of the coordinated effort for the functioning of the ballet troupe:

How much input do the dancers themselves have? The choreographer asks one dancer to imagine the evolution of the entire piece, not each step, which she must perform as choreographed but with her own motivation. Another listens to the psychology of Medea compared to that of the X-Men or Edward Scissorhands — “They all want to be in love but have dangerous gifts…” Soon the question arises: Can the choreographers, most of them a generation or two older than the dancers, perform the steps themselves, even to illustrate? Some do. But consider the plasticity of Marie-Agnès Gillot and her “splits” en pointe. “Try to do that at age 45,” remarks the Artistic Director. Or take one look at Gillot as she flawlessly turns twenty-eight pirouettes in a row, the first seven of them double ones. Then a pair of young women does a complex routine in unison and we overhear the male teachers commenting, “These two are incredible: you just have to plug them in, they’ve done it so many times.”

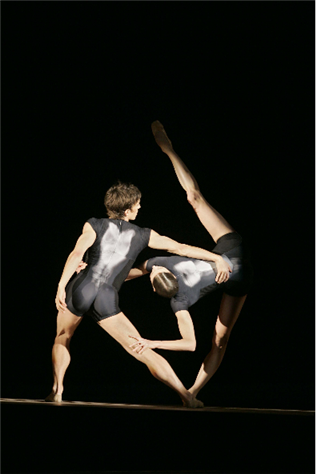

Marie-Agnès Gillot and Benjamin Pech in Genus

“It takes time, a lot of time… So it’s also a transmission of knowledge from the ballet masters… there will be a lot of dedication and teamwork within a cadre of ballet masters and their assistants who will make it happen. This task must bring people together. It’s not about having different views. Everybody must unite around the work. I find it very important to collaborate in order to achieve the best possible result. To me, the final result has to be a gift to the public that they can feel without any explanation.”

The Costume Workroom of the Paris Opera Ballet

Characteristically, Wiseman is interested in revealing all the workers of the operation and not just the most visible ones, the “prima” dancers, and the most powerful ones, such as Lefèvre or the millionaire patrons who attend her black-tie fundraiser. So we see here, with some detachment and irony, kitchen workers in hair nets and white smocks outside the door for a smoke at dawn, men stitching appliqués to costumes, a woman dying fabric and spray-painting soft ballet slippers, make-up artists for the ballerinas, and a hair stylist at work (the counterpoint is stunning) who herself is sporting multicolored, jumbo-yarn “dreds” in a loosely braided pony-tail. All alone in the dark theater a man mops the marble floors of the balcony boxes and vacuums (some) of the 2,200 velvet seats in the plush old venue. Up on the roof a beekeeper tends to the production of honey by the swarms around his veiled face. Plasterers and painters restore the offices the building houses. Meanwhile, meetings are held, both in these offices and on the studio floor, where Lefèvre discusses the “Special Retirement Systems” for the Opera, the Comédie Française, Gaz de France, the National Railways, and, of course, the Paris Opera Ballet: dancers have a special position even within this special set, with pensions available at age 40. In other words, she explains, “The dancers need to become aware of what it means to belong to the Paris Opera Ballet, of the reputation, quality, and integrity of the troupe.” She notes that she is speaking not as an administrative manager but as an artistic director who serves an audience of 300,000.

The Entire Company of the Paris Opera Ballet

So back to her claim of dance as a gift to the public that can be “felt without explanation,” because it’s one she shares with Frederick Wiseman. Cinema, also, must be felt without explanation; and here again, the director’s role is both less and more. We will never see him within the frame of the film, nor hear his voice, nor even know that he is behind the scenes, but his so-called “direct observations” are carefully thought-out and orchestrated choices as deliberate as those in a theatrical film. The distance of the camera (so as to include the full body of the dancer in motion and in relation to the others) and its placement (so as to avoid reflection in the hall of mirrors that is this dance studio or to play up the refracted images of an individual body in a half-dozen separately angled, adjacent mirror panels), the ambient sound that Wiseman records himself and chooses to use or not, and certainly the editing scheme employing fades to black and static shots of the cityscape at varying times of day to open the film out from its enclosure and point to a context — all are fundamental to the vision and voice of this documentary.

It’s often the associative editing within the designated space of the Palais Garnier that delivers the feelings of the dancers. A montage from stage lights to four different shots of natural light humanizes the dancer’s world: soft daylight falls into the dome-shaped rehearsal studio through deeply recessed arched windows that surround the floor like so many eyes, and this daylight finally frames the silhouette of a dancer standing before a window looking out — another kind of “spotlight” entirely. In Wiseman’s hands the 19th-century neo-Baroque edifice of the opera house becomes an intuitive analog for the dance the actors learn and perform. With Lefèvre on the phone vocalizing her worries about harmony and “the fear that nothing connects,” what we see is cinematographer Davey’s exquisite play with shadows in a sequence of shots of the configurations cast by the iron grillwork of the windows in astute juxtaposition with the geometry of forms the dancers are creating. Like the subterranean labyrinths that circle the Palais Garnier (and in the end become waterways with fish and lilies!), the dancers glide, leap and twirl, and the architectural and human images revolve in association with each other. The building and the camera — the geometry and play of light of the edifice and the dancers alike — speak a thousand words to show us that Wiseman’s “vérité” is neither random nor objective, but a passionately felt, selectively and subjectively structured reality fiction of the process that is dance for the Paris Opera Ballet.

La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet

Director: Frederick Wiseman; Producers: Pierre-Olivier Bardet with Idéale Audience and Frederick Wiseman with Zipporah Films; Cinematography: John Davey;

Editor: Frederick Wiseman.

Dancers: The Stars — Émilie Cozette, Aurélie Dupont, Dorothée Gilbert, Marie-Agnès Gillot, Agnès Letestu, Delphine Moussin, Clairemarie Osta, Laetitia Pujol, Kader Belarbi, Jérémie Belingard, Mathieu Ganio, Manuel Legris, Nicolas Le Riche, José Martinez, Hervé Moreau, Benjamin Pech, Wilfried Romoli, Isabelle Ciaravola, Mathias Heymann. The First Dancers — Nolwenn Daniel, Ève Grinsztajn, Mélanie Hurel, Myriam Ould-Braham, Stéphanie Romberg, Muriel Zusperreguy, Yann Bridard, Stéphane Bullion, Christophe Duquenne, Karl Paquette, Stéphane Phavorin, Emmanuel Thibault.

Color, 16mm, 158 minutes. In French with English subtitles.

Photos courtesy of Zipporah Films, Inc. www.zipporah.com