7-14-10

By Diane Sippl

I’m here waiting To get on this boat, I’m going to the sea, Even if it means I have to go walking.

Woa-oaaaa, walking there Woa-oaaaa, walking there There’s no hurry, no hurry to get there…

“Caminando,” Salvador Zepeda Mendoza, performed by Ganja in Alamar

Slowly, son. You have to be gentle… It’s a bird. She is a wild bird, who lives among other birds. We are too big for her. Slowly, slowly. That’s right — like that.

Jorge Machado to his son, Natan, in Alamar

I'd like to visit a place other than mine, get to know other people different from us.

Matraca to Jorge, his "son," in Alamar

When I moved to Playa del Carmen some years ago, probably driven by my childhood experience, many things had changed. What once used to be a fishermen’s village now was the epicenter of the fastest growing urbanization in Mexico. At this tourist-oriented development area, I’ve witnessed the lack of environmental awareness, the destruction of an extensive coral reef to make a long dock for cruise ships, the destruction of hectares of mangrove along the coastline to build big chain hotels, polluting the sea with sewage water, hence affecting the whole ecosystem of the area and pushing many of its species to an ill-fated future… By photographing and developing a story based on the current relation between man and his habitat in Chinchorro, I intend to portray my love for this region and the admiration and respect I have toward the lives of its fishermen.

Pedro González-Rubio is a Mexican

filmmaker born in Brussels who was initiated

into the visual arts as a teenager when he lived in New Delhi.

He studied media in Mexico

and also attended the London

Film School

before working as a cinematographer, making short documentaries for an ecology center in the Yucatán, and co-directing his debut, Toro Negro, in 2005. Both that film and Alamar, his own feature film debut, have won numerous top awards at

international festivals in Morelia,

Rotterdam, Buenos Aires,

San Francisco, and San Sebastian. As Alamar travels to festivals around the world (in Japan, Paris, and Edinburgh, for example),

González-Rubio has attended the 56th Robert Flaherty Film Seminar, where Alamar was screened. He wrote, directed, co-produced,

photographed, edited, and designed Alamar. We met to speak about his film last May when it played at UCLA's Melnitz Movies.

Filmmaker Pedro González-Rubio

A dream in a bottle tossed into the waves. A child's drawings of stingrays, barracudas, crocodile teeth, a bird — and a camera — signed, folded, and pushed through the neck of a clear gallon jug with a red blossom already there. In his uniquely intimate song to the sea where the imaginary is a fact of the real, Pedro González-Rubio approaches

the lyrical narrative as no other filmmaker does. This is a bold statement considering the comparisons that abound: the first decade of this century sparkles with hybrid works from Mongolia to Argentina, Kazakhstan to Colombia — just to hint at the many gems of the “real” that have been recorded

yet enacted for the screen and that finally forced many film festivals to eliminate

sections entitled “Documentaries.” The ethnographic "home movie" is no stranger to Mexico: Dariela Ludlow Deloya films her elderly grandparents in Acapulco in One Day Less while Carlos Hagerman and Juan Rulfo travel from family to family, from Zacateca to Mérida, in the talking tales of Those Who Remain. Carlos Reygadas’ metaphysical allegories enlist non-actors from the locations. His company, Mantarraya, produced Alamar, and his regular cinematographer, Alexis Zabé, shot the underwater footage with David Torres while González-Rubio shot the entire balance of the film with a single HD camera.

Still, Pedro González-Rubio has made a new mark: with stringent means and radiant simplicity, he has created an epic coming-of-age tale with a five-year old boy. (Another critic mentioned that when this protagonist was introduced in the theater at the Toronto Film Festival, his pastime during the whole documentary-fiction dispute was to “run wind sprints up and down the aisles.”) What’s astonishing is how this other-worldly adventure, introduced symbolically by a window we see built on-screen in real time, serves as concrete aural-visual testimony of Natan Machado Palombini’s own life, catching a moment in time that might be the biggest transition a child can make yet presenting it as one he can value forever, because he has had a taste of how it all works.

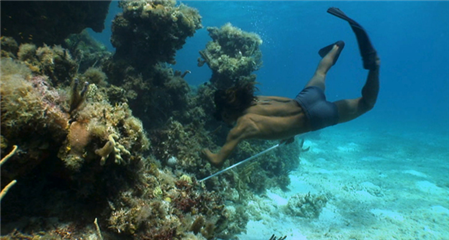

Natan’s Mexican father, Jorge Machado, and his Italian mother, Roberta Palombini, are splitting up. Their love affair was heaven — it begot Natan. But now Roberta tells Jorge, over a montage of their own romantic sight-seeing images, “I’m unhappy with your reality, and you are with mine.” She and Natan live in Rome, and Jorge, as she sees it, “in the middle of the jungle at the sea, in the middle of nowhere.” Before parting with his child, Jorge wants to show him his origins. By bus, foot, and boat, they arrive at a house on stilts in Banco Chinchorro. González-Rubio lets the water take us there — to a mystical-real coral reef where time moves in waves like the sea and this boy, little by little, discovers the world of men. Buoyed in paradise, suspended in space, swaddled in a blue mesh hammock like a tiny fish in a net, Natan awakens to a speechless peek-a-boo with his father, who over the days includes the boy in painting their palafitte, pulling the catch, scaling the fish, sorting the lobsters, cleaning the boat, dodging the crocodile, befriending the bird.

“Ready, my love? You want to see the corals and the fish down there? Do you want to see the stars and the snails? You want to see the sharks? Well then you have to use this, so you can stay longer under the water…” the father says, letting go of the boy’s hand from the boat as Natan plops frog-like in the sea, face down, snorkel up. It’s his first time.

In large part, it is learning to value labor itself that structures Alamar as an odyssey from mother to father, Italy to Mexico, urban life today to the natural world of ancient ancestors — and back again — but it is also learning to dream. Whether snorkeling with his dad in the Caribbean or perched on a hillside overlooking Rome at the film's end with his mom and a jar of liquid soap, Natan is able to claim, “I can blow big bubbles.” And no matter that they drift off or even burst — he has also learned to let go. At the same time, he has learned to live in the moment and to respect the past.

With its subjects of

father, son, and grandfather (lay actor, Néstor “Matraca” Marín), Alamar might well be one of

the most beautiful documents of male bonding you will ever experience. The film's metaphors creep up on you as if no one had ever coined the word. Taking this journey with Natan imparts a feeling so pure

you want to bathe yourself in it forever more.

You hold onto it as you would a deep, clean breath. You want no intrusions into the lull of its

rhythms, the harmony of its elements, its gracious space. Is it fiction? Is it fact?

It is life — and thanks to Pedro González-Rubio, it is cinema. In the end credits, the filmmaker thanks Mother

Nature and dedicates his work to his grandfather.

Diane Sippl: Banco Chinchorro, the location you chose for Alamar, the richest coral reef in Mexico and part of the second-largest of the planet, was designated in 1996 as a Natural Reserve of the Biosphere by UNESCO and may soon be declared a World Heritage Site, with its thousands of species of unique wildlife. Correspondingly, your themes in Alamar are deeply resonant — so local and specific to individual lives and yet so universal across eras and cultures. How did you choose your subject matter?

Pedro González-Rubio: I’ve been living at Playa del Carmen, which is on the Mexican Caribbean, for seven years. It’s where I developed Toro Negro that I made five years ago. I followed that character with the goal of going to the deepest core of his inner life and his surroundings, and I discovered a very tormented guy and very dark story. So after that I wanted to do something that could restore the balance for me, like the ying and yang.

It would be another family story, but portrayed from a different point of view — how love is pure and unconditional. For me it’s a very honest picture. It reflects a lot of independence, which is something I look for as well, because that’s my idea of filmmaking — a lot of freedom, and independence from a huge crew. When I shot Alamar there were only two of us, myself and a good friend of mine who did the sound, so there’s a strong relation between the filmmaking style and the lifestyle inside the film.

In the beginning it was a story about a man who was going to spend his last days in the place of his origin. When I met Jorge — he works as a tour guide one hour from where I live — his personality attracted me; I was instantly fascinated with him. But then I said, well he’s too young to be a man in his last days of life. So then it came to me why I wanted to do a story there, at this specific location, with this specific character. It was a story that could portray a love for nature, but nature also being ourselves, and ourselves being our siblings. So that’s how I discovered Natan, Jorge’s little son. He came to me — he was a continuation of life.

It’s a voyage of initiation, basically. As I got to know Jorge’s life, I tweaked some of my story. I said, okay, we’re going to do it in Banco Chinchorro, with this fisherman, Matraca. I was location scouting, and I was just “cooking,” like a chef, mixing all the elements. I had some ideas before the trip that I wanted to explore. The most basic was work — how through work, the bond between father and son grows. This included some activities besides fishing, such as cleaning the boat with natural sand and painting the palafitte, his house, but from the inside, bringing the sun inside, into the soul.

But it doesn’t really matter, because the film can work on many levels, and what I wanted to focus on was letting people feel all the sensations that Natan feels. I wanted to bring people to the location.

DS More often than not, Alamar is a like a textbook example of what I’d call “pure cinema”: the movement of images and sound through time and space — in this case, poetry-in-motion. Yet with very few words you are literally documenting an important real event in the lives of the people we see on the screen in a place that means the world to them. How do you reconcile this approach with theatrical filmmaking, in which you direct actors and set up particular shots in staged scenes? Were Jorge and Natan, father and son, equally comfortable with the camera? Did they rehearse lines or actions? Did you direct them?

PGR The easiest to work with was Blanquita (the bird) and then Natan. For Natan, I went with him to his kindergarten with a camera, because I wanted to have a knowledge of his personality, and also for him to get used to the camera and to have confidence. But working with Jorge was different. He was more conscious of his appearance. Even during the shooting, even after the first week, I was still telling Jorge to bring down certain aspects, that he didn’t need to act. So finally I put him to work, and his best moments were those when he was focused on scaling fish, or painting, or doing something with the boat. Every time he had another activity that didn’t involve talking and he could just concentrate on work, he was good.

DS Is the older fisherman, Matraca, really Jorge’s father and Natan’s grandfather?

PGR He has no blood relation to them. I found Matraca at the site. As I was scouting various locations in the Mexican Caribbean, most of them were very close to hotels or tourist developments. A friend of mine who’s a biologist kept telling me about a place where people lived on wooden sticks — whew — so when I was able to get there (because it’s very difficult to get the tourist visa, but with him I was able to go) I was definite. Inside a house was the location where I wanted to film, and I asked which one I could use. One of the managers told me, “The fisherman who lives in this one is my friend.” So we talked. And then I met him. He was sitting there cooking bananas. Yes, he smiled, and his laughter was so beautiful. It wasn’t really just casting characters; it was, “Oh yea, this one” — you know, as if you have a botanical garden and you’re a cook and you say, okay, now I’m going to add some of this plant, and you start building up the idea of going back to the origins, and what is important for the world. For me, it’s going back to very basic activities and discovering the simplicity of happiness — just having coffee, watching the stars.

That’s why the music in the beginning of the film says, “There’s no hurry to get there.” So little by little, it works unconsciously. I wanted to get the audience into this rhythm of the sea, of the lifestyle of the fishermen, to be totally relaxed, as if being massaged.

DS How big is the fishing community that actually lives like this?

PGR There are forty fishermen living there, and all their families live on the coast in various villages and cities and also in the city of Chetumal The men spend between two and three weeks in Banco Chinchorro fishing. Every day they take the lobsters and fish to the ship, and once the ship gets loaded with fish, the captain takes it to the coast and they sell all the fish to the distributors. But the fishermen really love their independence, so they’d rather stay a longer time in Chinchorro than on the coast with their families. They are organized in three unions there, and they get a lot of help from organizations that protect and support their activities. These fishermen and the way they fish are part of the heritage of this place.

DS Where, exactly, is the fishing location?

PGR This is a coral reef, Banco Chinchorro, and it’s twenty miles

from the coast. The nearest village on

the coast is Mahahual, which is almost between the reef and Chetumal, which is just

north of Belize. From Mahahual we went by boat for almost two

hours to arrive at this reef and those houses, called “palafittes.” This setting, so minimal, was the ideal place to see the people and their relationships grow.

We made two trips in total to the

location, and on the second trip a particular bird arrived, a cattle egret,

because there were a lot of cockroaches in the shack and she spotted them from

the air. (Cattle egrets eat bugs from

the cattle.) Jorge is self-taught in

ornithology, the art and science of bird-watching. And he also has a very mystical quality to

him. So when you combine this scientific

passion for birds with that mystical quality, you have somebody who had a very

special relation to this egret, and I used this as a parallel with Natan’s own

learning experience.

When I was a child, we had frogs in the garden, and I remember thinking, “Oh, I want to have this frog.” But you can’t have the frog — it’s too wild. So it’s a learning experience of letting go — and also of continuing on with one’s own destiny. When the cattle egret came back twice, it was almost a miracle. I really believe in signs, and for me it was a very strong sign. And even though I don’t think of myself as some mystical filmmaker, sometimes I have to believe that only that one reality can happen. And if I had arrived with a very structured script, I would never have watched the bird. I would have said, “Ah, the bird — it’s going to land. Okay, let’s go to the scene.” No, I was really paying attention to every single motivation that nature was bringing to me. When the bird left, I thought, this is perfect. It’s perfect to go and search for Blanquita and actually not be able to find her. I knew that we were not going to find her, but Natan didn’t know that. So I said, “Natan, we should go look for Blanquita,” and he was really into it.

DS Were his tears about not finding her?

PGR No, the tears were entirely about the fact that it was our last day in Chinchorro, and I was telling Natan to pay attention to what his dad was going to tell him. I was very confident of Natan’s intelligence, and that he would listen to Jorge’s words, and I gave Jorge a lot of time to say whatever he wanted to tell Natan. And I told Jorge, “We’re here for you to say good-bye to your son because he’s leaving.” And Natan just really got into it.

DS You shot the film

yourself. Did you go about it in any

special way? Are your scenes captured, or composed?

PGR As for the camera set-ups, once we had the scene — let’s say the father and son taking a bus from Playa del Carmen to Mahahual — then I started covering, taking different shots, in order to use them in the editing. But in the end I had only 35 hours.

We began with a discussion with the whole community before-hand. When I first arrived and decided on the location, I had a meeting with all the fishermen there and told them I was going to come with my camera and another friend, with his boom, and that we were going to make a film and that Natan was going to be in it. I explained what the film was about. They were all very conscious of what we were doing, and very helpful as well.

I’ve seen other film production teams that come to these locations and they just interfere with everything. They impose on everyone, saying, “So now, lady, you’re gonna live here,” and “We’re going to take this from that house and this other thing from here,” and “Can you please — we’ll rent you a hotel room for three weeks in another place, and put the catering in another house.” And I thought, my God! No. I’m going to live the life Matraca lives. I told him we were going to make this film, but little by little, and the main thing was to accompany him during his work and for me to try to do what he was doing as well. So I learned to fish. I cooked with them. It took about a month and a half of being there, but most of the time, my sound recordist and I were doing the activities that you see in front of the camera. So we were not in a hurry. We were really getting integrated with the time and space instead of imposing on the system — like sending out “wake-up calls,” or yelling, “Cut!” because one union or another has used up its time.

DS You are quite self-effacing in your camera style, yet the end of the film, Natan is reflecting on what he has seen on his trip, and he mentions the camera. Did he see the finished film? What about the others — did they?

PGR The whole family came with me to a film festival in Mexico called Morelia Film Festival, and after that I showed it to Matraca. He was supposed to come to Morelia, but when he went to catch the airplane, he arrived late at the coast. But he had seen it already. In Banco Chinchorro, we had a screening with the fishermen there, and they were surprised to see it — because they are used to watching what you see on the TV monitors in the local taverns. Alamar was very emotional for them to see. It gave them a lot of self-awareness.

DS Is Matraca speaking Nahuatl? Or Spanish? Is anyone speaking Mayan?

PGR This region of Mexico

is Mayan, and Jorge is of Mayan origin but from

DS How much of a script did you have going into it? Did you have any dialogue at all? How did you break down the outline of what you would shoot? Was it more of a shooting script? Was there any narrative outline?

PGR Basically there was a treatment that I had before going to shoot in the first days in Banco Chinchorro, and this treatment talked about how going to the location was a painful process for the boy because he was being taken away from his mother, and then how, by the day-to-day activities, the bond between father and son would grow and grow and grow. And then I asked myself, what else beside the separation and the trip should I focus on? Oh, painting the palafitte from the inside, because that would be bringing the sun into your own soul. And then, after watching what Matraca and the fishermen do there, I said, okay, I’m going to do underwater shots while they fish for lobsters. I’ll shoot this fishing outside, and then going to the mother ship to deliver the goods, and then some very intimate scenes of father and son bonding together, along with having dinner and having lunch. But all the dialogues and all the ways of resolving the scenes were decided on location, on the spot.

What I had was this: Point A. Introduction: mother and father meet, they break up, but they have a child. Next point: Mother is going to Italy, but father decides to take his son on a last trip. The father-and-son bond grows and grows and grows on this trip. And then, father has to say good-bye to his son. Point C would be: mother and son in Italy.

DS So you started with just that sketch. But you said there was also a lot of writing.

PGR And then there was a lot that came up during the filming. Blanquita turned up, which struck me as completely out of reality — how to deal with this element? I would say it’s very intuitive: if I were Natan, maybe I would go and look for Blanquita. So I actually created a lot of the scenes. They were like guidance.

DS So this is what you mean by writing.

PGR Yes, on the spot.

DS It’s what makes your film fundamentally lyrical — its own organic stretch to reach for something “more,” that is at once elusive and attainable, temporal and timeless, documentary and fiction. You’ve said there’s a lot of painting in the film. Of all the arts, which one do you think most inspired or influenced Alamar?

PGR Oh definitely music.

DS Really? Tell me about that.

PGR Yes, music is very present in my everyday life, and it was also present when I filmed. Usually with an iPod I’m listening to guitar music by someone like Agustín Barrios Mangoré (from Paraguay) or very Berber music from the North of Africa. I like Moroccan, but I like all types of music. It has inspired me a lot. It gets me the tempo. Even gospel.

During the editing I use a lot of music. And then I take it out. And then what stays is the rhythm. So when they are crossing on the big boat, father and son, and father is holding his child in front of him with one arm wrapped around him, and we’re all feeling very seasick, well all of that scene is made with a song from Sweet Honey In The Rock, which is an acapella gospel-soul, all-woman group. I edited that scene with their song, “Wade in the Water.” I remember that scene was so powerful for me with that song, its rhythm, and then I took the music out. Just the spirit remains there.

DS I think you’re right about that rhythm being really felt, present, without being conspicuous, and it leads to another one of my questions. In the film itself, the final product, either from the beginning or in the end when you edited, how did you decide how to use music — how much to keep in the film and where to use it?

PGR I wanted to use just one theme. The film begins with this theme and it ends with the same theme, to make a circle, the cycle of life. It was composed for the guitar, but then I invited a friend who plays the oud, Fausto Palma, to interpret it, because the oud is more ancient than the guitar, and I wanted that sound of an ancestral instrument for this ancestral film.

DS And how did you decide how much dialogue to keep in the film? There is very little spoken in those 73 minutes. Was that your idea from the beginning, or did you keep taking it out when you found you didn’t need it?

PGR No, from the beginning I wanted little dialogue.

DS So you even taped very little dialogue during the shooting?

PGR Yes. The same as the rhythm there. Actually the grandfather talks a lot, but I was trying to be very contemplative. I believe I kept the power of silence. Many silent moments are much, much more powerful than those with sound. Even when they are sleeping there is a beautiful gesture in which the father puts his hand on the son’s chest. With just that, you don’t need to have a dialogue saying how much he loves his son. Just that gesture. It says, I love you, and I know that you’re leaving, and I want to protect you and I don’t want anything to happen to you — just that gesture — all of it is there in that gesture.

DS That was an incredible scene. That image is unforgettable. It says even so much more than that. And, about images, I’m wondering how you decided to open the film with the black-and-white family photos and home movie.

PGR It’s their own footage. It’s photographs and a video from their own archive, because I tried another beginning. We did a beautiful scene of Roberta and Jorge. It started with a farewell between mother and father. But it didn’t introduce the characters properly. So I really needed something very short, and real, in order to engage the audience with the story of their lives, to give the audience enough information so that then I could start writing poetry. The mother understood that when she was getting Natan his shower; there is enough information already to know who is who.

DS That opening is very immediate.

PGR It means, “We met like this. It was beautiful.” Then it’s like ping pong: Roberta says this, Jorge says the opposite… Jorge’s more of an idealist, the same as me. And the mother’s more a rationalist, saying, “Well, Jorge, we just don’t work together. It’s as simple as that. We’re not together because our realities don’t match.”

DS Alamar often seems to work in trinities.

PGR Yes, there are often three layers in the film. The grandfather is knowledge, ancient knowledge that is still capable of controlling lots of skills. And there is the young man who has forgotten his skills, because he’s already living as a bartender or tour guide. He has a visa to go back, and he’s saying good-bye to his son. And there’s the son, the boy who has to discover; he’s initiated. So we have three different levels, or stages, of a man. That’s why I think the flag for the palafitte, with three dots, is a representation of the film, because there’s also a mother, father, and son; there’s sky, ground, and sea. But I’m not a Catholic or anything like that….

Alamar

Director: Pedro González-Rubio; Producers: Jaime Romandía, Pedro González-Rubio; Screenplay: Pedro González-Rubio; Cinematographer: Pedro González-Rubio, (underwater photography by Alexis Zabé and David Torres); Editor: Pedro González-Rubio; Production Designer: Pedro González-Rubio; Sound: Manuel Carranza; Music: Fausto Palma, Juan Andrés Vergara, Diego Bellinure, Uriel Esquenazi, Salvador Zepeda Mendoza.

Cast: Jorge Machado, Roberta Palombini, Natan Machado Palombini, Néstor Marín “Matraca,” Garza silvestre (wild egret “Blanquita”).

Color, widescreen HD-to-35mm, 73 minutes. In Spanish and Italian with English subtitles.