6-12-20

Yourself and Yours: Hong Sangsoo Angles in on a New Frame of Mind

By Diane Sippl

Well, no one told me about her

The way she lied

Well, no one told me about her

How many people cried

But it's too late to say you're sorry

How would I know, why should I care?

Please don't bother trying to find her

She's not there

Well, let me tell you 'bout the way she looked

The way she acts and the color of her hair

Her voice was soft and cool, her eyes were clear and bright

But she's not there

The Zombies

“Haven’t we met somewhere before?” It’s a pick-up line if you ever heard one. And you hear it more than once in Hong Sangsoo’s latest dramedy of errors. The fact is, Minjung has gone missing. She’s had enough of Youngsoo’s accusations and insults, so she gets up from his bed, gets dressed, and walks out the door. The next day her woe-begotten beau tries desperately to find her.

How much you like Yourself and Yours might depend on how much you like to view a film twice, even if it’s only 86 minutes long but if it also happens in homely settings—an artist’s cluttered studio, his makeshift bedroom (or just his mattress with a pile of books beside it on the floor), casual neighborhood bars, a roadside bench—you get the picture. Your patience might also be tested by repeated dialogue of the most banal sort: rumors, gossip, attributions, denials, flirtations, all in several cycles. Then your tolerance level for drinkers might come to the fore. “Only five drinks? Give me a break!” taunts Youngsoo. “Alcohol is dangerous” claims a young woman who is inscribed with innocence. But there is also the remark, “Don’t we drink to get drunk?” from the same character—or is it? And this is one of the most perplexing reasons you might want to give up on the film: you might never find out! But does that mean you’ll quit, or you’ll simply watch it again, seeking to find out why you don’t know and what you missed.

Hong Sangsoo is a brain teaser, and one of the most philosophical sorts. Since 1996, he’s made 25 feature films (that’s a film a year, if you count his new one coming up), and they each bear his mark as an auteur in the footsteps of Eric Rohmer, for example, relying often on his small cadre of actors in everyday situations that offer moral commentary on South Korean life, yet it often arrives in the most oblique way. His humor is strange; sometimes it doesn’t feel funny at all, and maybe it’s not, but the irony lingers. In fact, his latest handful of works have often transpired in the midst of grave situations—the illness of a mother or the death of a father or the loss of a loved one—opening to ponderous soul-searching on the part of his male characters. Can it be that these days it’s still unusual to find genuine male humility and self-reflection, especially hot on the heels of overt female self-expression, and that exactly these behaviors take center stage in motivating the thematic development of films? If so, it’s one reason we keep watching Hong’s films, over and over. Something in traditionally inscribed gender roles seems to be giving way....

Hong plods through his ominous tale at the pace of his limping protagonist. Yes, Youngsoo stumbles along on crutches for a reason not specifically disclosed. And one of three possible doppelgangers of his sweetheart, Minjung, wears a black patch over her eye. She’s quite tipsy, at that. Is she partially blind? Or was she, perhaps, in a barroom fight, as rumors have it regarding Minjung? Youngsoo is drinking alone (three bottles appear on his café table), and this pirate-like version of his girlfriend invites him to join her buddies inside. Dejected, he declines. Of course, mention of his dying mother has set the tone at the outset of the film, but you won’t see the mother—only the son’s obsession with his flame.

Speaking of which, peculiar attention is paid to a candle beside Youngsoo’s bed. Near the end of the film, the camera zooms to its flame, then a few inches lower than it was at the beginning of that scene. Could this be one bookend of a dream (the other bookend within it)? Or maybe it’s not technically a dream but rather a projected scenario, Youngsoo’s but also not unlike those of two other men who swear they’ve met Minjung before. Another time, another place, but same “girl.” That’s another thing—she tells them that the men she meets either “fool around like kids or pounce like wolves.” Why are there no decent men?

Two scenes rely upon a shop window mannequin. In the first, “she” faces us in between two men gazing into the window looking for Minjung, who’s not there. In the second, the mannequin, “looking out,” is center-frame between Youngsoo on the left, peering in, once again, and the mannish-looking female employer on the right inside, who reiterates, “She told me not to tell you about her. Go. I have work to do.” She removes the arms of the dummy, one at a time, dismantling the figure, lifting off its pink dress, preparing to change it.

There’s more pink—the pale pink mail box at Minjung’s front door that fills the frame once Youngsoo leaves in vain—its two hot pink holes side-by-side like “eyes” with a padlock hanging where the mouth would be. The camera lingers there after the sad-sack lover gives up and goes. There is yellow, too—a transparent lemon-colored plastic piggy bank glaring from the left edge of the frame on a bar room counter. (It’s hard not to recall Hong’s first feature, The Day a Pig Fell into the Well.) And there’s the ubiquitous emerald green shoulder bag “all” the “Minjungs” carry as she saunters to her regular haunts while Youngsoo wanders in his odyssey to find her. Her simple clothes change somewhat throughout the film, but the green bag remains. Does it mean you have the real Minjung each time, and she has indeed been lying to the gray-haired married man and the male filmmaker, both with whom she goes drinking? Youngsoo’s gossiping friends have their eyes on her, even when he doesn’t, and as they drink, they say she drinks too much. “You smoke too much,” the bartender tells one of them. “I can’t help it,” he replies.

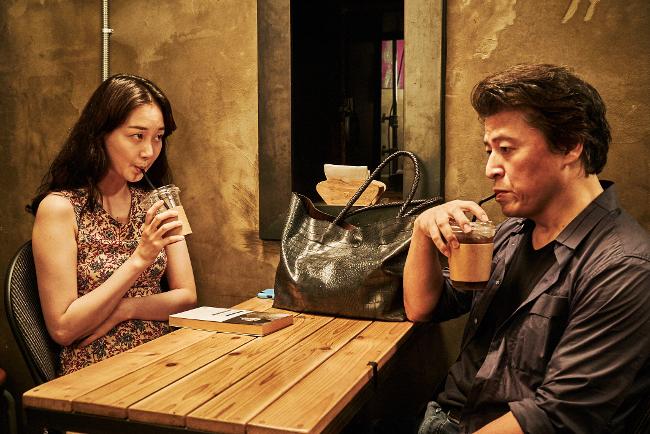

Yet the rumors, the ubiquitous green bag, and the lies—are these the point? Hardly. They color the frame, fill the story, and raise your ire. But did you notice the camera angles? Always on Minjung’s face. The men get a quarter-profile at the same table, or an over-their-shoulder point of view shot at best. You don’t need to see their eyes, their lips, uttering their words. Youngsoo weeps in a sobbing drunk scene, “I never saw her do wrong. I never heard those words from her lips.” It may well be that you’re seeing his off-screen point of view on Minjung (and himself) through the course of the film, but she’s the one who motivates the camera. When you see her in the second bed scene, her face for the first time falls under increasing shadow—that is, until the final shot, when she returns to the bed in her original T-shirt with a tub of watermelon—“So refreshing...”

Yourself and Yours

Director: Hong Sangsoo; Producer: Jeonwonsa Film; Screenplay: Hong Sangsoo; Cinematographer: Park Hongyeol; Editor: Hahm Sungwon; Sound: Kim Mir; Music: Dalpalan; Lighting: Yi Yuiheang; Recording: Seo Jihoon.

Cast: Kim Joohyuck, Lee Youyoung, Kwon Haehyo, Kim Euisung, Yu Junsang, Bek Hyunjin, Kong Yoonyoung, Joh Ung, Suh Hyunjeong, Chang Jayoung, Kim Minjeung.

Color, 86 min., Korean with English subtitles.

Playing at Film at Lincoln Center Virtual Cinema