4-20-14

Sixteen-Going-On-Seventeen: Ozon’s Young and Beautiful at COLCOA

From April 21-28, 2014 at the Directors Guild of America, the 18th annual City of Lights – City of Angels week of French premieres in Hollywood brought 41 theatrical features and documentaries and 20 short films to its largest audience ever, nearly 20,000 viewers. François Ozon's work was once again on the screen (seen last at the 2013 COLCOA) and it stirred talk early on in the festival.

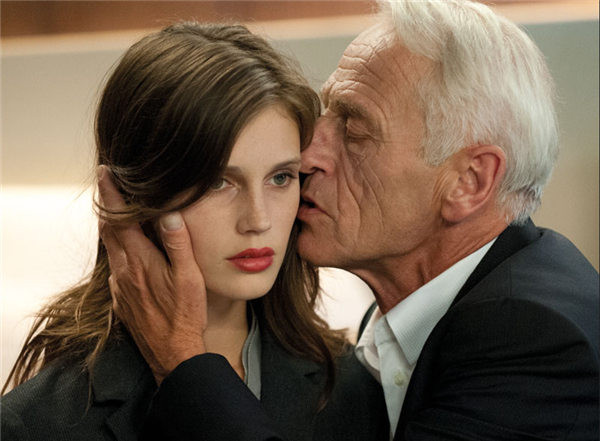

Young and Beautiful — it sounds better as Jeune et Jolie, the name of a teen magazine in France; the French title for François Ozon’s latest film points to a wry analogy with the first career of his leading lady, model-turned-actress Marine Vacth, who truly “walks the walk” even if she doesn’t “talk the talk.” She plays Isabelle with coy mystery. Choosing to lose her virginity in the summer of her 17th birthday, by that autumn she takes it into her head to become a prostitute. It’s easy enough to do these days, it seems, by setting up your own website portfolio. She craves the exhilaration of choosing her clients, taking their calls, negotiating her fee, stealing out the door of her upscale home with her mom’s silk blouse, smart black stilettos and blazer tossed into her huge leather tote, hooking up in swanky hotels or underground parking lots, but mostly opting for the high-end Johns (or is it “les Jeans”?) who plunk down €300-500 a pop at luxurious venues.

It’s not that she needs the money. We can see from glimpses of her daily routines that she lives in a comfortable upper-middle-class family with her mother, brother, and step-father, all congenial enough, thoughtless as they may be. No one locks doors in this home, and no one knocks before entering. No one stops having sex, with self or others, or talking about it. The step-dad crosses the hall naked. A boyfriend who sleeps over in the daughter’s bed is welcomed to the family breakfast table. Still Isabelle apparently enjoys a streak of rebellion. A Baby Belle du jour, many have called her in the critics’ circle, but she’s both beyond and before Buñuel’s role for Catherine Deneuve.

With no prologue of fantasy such as Buñuel offers, Young and Beautiful opens with realism and voyeurism. Binoculars frame the opening shot as Isabelle drops her bikini top to sunbathe on a secluded beach. Soon enough that double lens leads to a double point of view as Isabelle gazes upon her own deflowering, which leaves her with much to desire. That shot veils the rest of the narrative in another light, even as each season opens with a different character’s point of view, from her brother’s in the summer, to her client’s in the fall, to her mother’s in the winter, to her step-father’s in the spring.

Stepping lightly, Ozon gives us

all of their perspectives on Isabelle, elusive as these glints of her character

may be. He also shows her interactions

with a girlfriend who invites her to a party, with a male classmate she meets

there who would like to be her boyfriend, and with her mother’s friend who

hires her to baby sit and doesn’t know Isabelle’s mother is her rival The film also shows us the teenage call

girl’s interview by the policewoman who caringly numbers off to her the reasons

it’s against the law for Isabelle to meet her clients; in addition, we witness

Isabelle’s session with an older male psychoanalyst (Serge Hefez, expertly

playing himself in his own office) who enthusiastically supports her idea, to

her mother’s chagrin, that Isabelle pay his fees from her earnings as a

prostitute. Here we learn that

Isabelle’s father has been absent with a life of his own in Italy and that her

mother blames him; yet maybe we learn more about the mother and the marriage in

this session than we do about the girl’s reason’s for prostitution. And that’s just it.

Young and Beautiful is not bent on pursuing the motivations or machinations of teenage prostitution today so much as following Isabelle’s enigmatic heart. Martine Vacth’s freckled face, gray-green eyes and russet tresses — all a fascination for the eye alongside her trim, girlish body — are reminiscent of another teenage rebel who came of age on the screen with equal opacity yet plenty of pent-up emotion over the years: Isabelle Huppert. Just a few years ago at ripe middle-age, she gave a tour de force performance as the dynamic lead in Jeanne Labrune’s Special Treatment (2010), better named in French, Sans queue ni tête. Huppert, with her impish looks coupled with a capacity for devilment behind her husky voice, has spent her whole screen life perfecting the art of elusive non-conformity as a vehicle for self-discovery. Judging by Young and Beautiful, Vacth is already well on her way down this path. (In real life, this spring, at 23, she becomes a mom.)

Ozon’s Isabelle appears less confused than her 19-year-old Tokyo counterpart in Abbas Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love (2012). Fresh from a small town in the south and prodded by a jazz-hall pimp, Akiko (Rin Takanashi) reluctantly turns tricks for money, one might say, to pay her way through college, but she strikes up a very different kind of wager with an emeritus professor who by default comes to know her more as a school girl than a call girl, much as her cute photos are plastered in public phone booths with her dial-up number. More to the point, that film is not so much about the teenage girl’s profession as it is about her chance relation with the elderly man as a step to her own self-knowledge. That same set-up operates in Young and Beautiful as we follow Isabelle from an older gentleman who is her first client, through others who are rougher, cheaper, and less predictable, and back to the same original client who pays her even more. There is a proverbial “tenderness” there — he actually looks at her, sees her, talks to her, even caresses her, and touches her as a person — and she’s not able to forget this when trouble ensues.

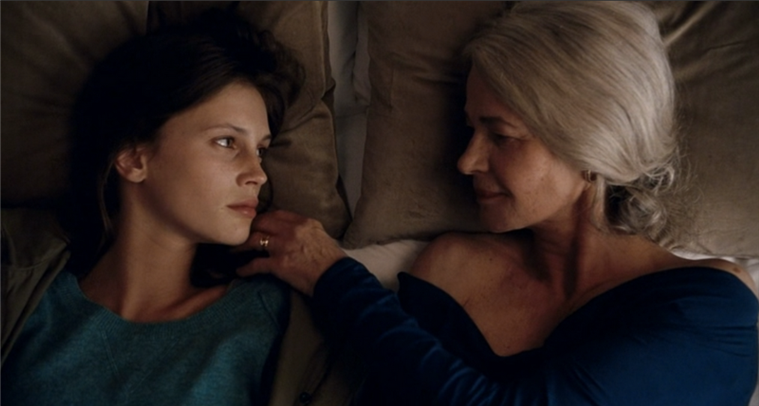

And that trouble vexes Isabelle, haunting her and provoking a self-confrontation as she attempts to get in touch with her feelings about other aspects of her life. A particular scene comes as a surprise for the film’s finale by re-enlisting one of Ozon’s best actresses, Charlotte Rampling, from another film of teenage sexual rebellion, Swimming Pool (2003), and another earlier one of the self-denial of emotions, Under the Sand (2000). Each film employs Rampling superbly as a woman superficially expressive among others but actually buttoned-up in facing her own sense of loss, unable to penetrate it on her own real terms. Laurent Cantet’s Heading South (2005) gave us Rampling as an affluent tourist buying sex, with quiet, selfish desperation and shocking collateral damage. She alludes to a woman her age in comparison with the teenage Isabelle in Young and Beautiful in a surreal scene that would be a show-stopper if it didn’t culminate the narrative. But it does more, opening up the portrait of this young girl looking in the mirror for four seasons of her 17th year and re-directing her gaze, at least in the story-telling, to us.

Rather than creating a lurid thriller or social-commentary drama or psychological study, any of which would be focused on the sex trade today as practiced by Isabelle, Ozon turns to how a girl gets to know her own body in relation to herself as she becomes a woman. And in his own typical fashion, Ozon employs his signature style — literature, women, and song — to get under the skin of the female figure his photographer captures so elegantly on the screen. Whereas Eight Women (2002) and Potiche (2010) used the musical and boulevard farce to a similar end, one parading the many facets of the feminine at various ages and stations, and the other limning a grown-up woman’s social and economic self-empowerment, here the writer-director structures poetry, pop singing, and once again, the surreal to get us inside the heart of the female subject.

A refreshing scene appears early on as Ozon includes documentary-like, direct-to-camera footage of half a dozen real high school seniors in their own school classroom reciting and then interpreting, one after the other, an 1870 poem by Rimbaud, “Novel,” written when he was Isabelle’s age. The first of its eight stanzas:

No one's serious at seventeen.--

On beautiful nights when beer and lemonade

And loud, blinding cafés are the last thing you need--

You stroll beneath green lindens on the promenade…

The youths’ responses sit comfortably beside the refracted perspectives on Isabelle, and the class’s reactions are in a way the best key as to what Young and Beautiful is all about. Four songs by singer, actress, and fashion icon Françoise Hardy also punctuate the four seasons of Isabelle’s year of experimentation/introspection by adding a playful female voice that, as her vocal alter-ego, complements her visual doubles that dot and bookend the film. Ozon’s otherwise direct, realistic camera style and traditional dramatic narrative finally reveal themselves to be a somewhat surreal probe, a self-portrait-in-the-making, an emotionally lush and lyrical foray into a young girl’s heart.

Young and Beautiful

Director: François Ozon; Producers: Eric and Nicolas Alt Mayer; Screenplay: François Ozon; Cinematographer: Pascal Marti; Editor: Laure Gardette; Music: Philippe Rombi; Production Design: Katia Wyszkop; Costumes: Pascaline Chavanne.

Cast: Marine Vacth, Géraldine Pailhas, Frédéric Pierrot, Fantin Ravat, Johan Leysen, Charlotte Rampling, Nathalie Richard, Djedje Apali, Lucas Prisor, Laurent Delbecque.

Color, 35mm, 94 min. In French with English subtitles.