4-21-13

Violeta Went to Heaven:

Andrés Wood Shows Us Her Life on Earth

By Diane Sippl

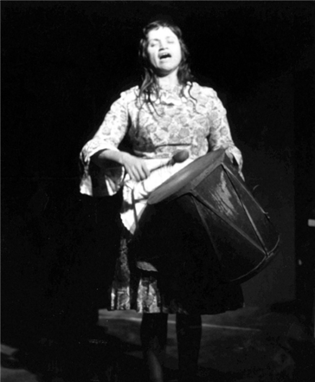

Francisca Gavilán as Violeta Parra, 1917-1967

(All color photos courtesy of Kino Lorber)

Leonardo Da Vinci ended at the Louvre. Violeta Parra started there.

Headline in the French newspaper, Le Figaro, 1964

… the province of Ñuble touches the full Andean summit, whose people work and indulge in some two hundred years of backwardness… But their antiquity transmits sagacity, in a past that is deeply profound, holding a perfect pulse on memory.

Patricio Manns, Violeta Parra, 1977

The day that I do not have a love to dedicate my songs, I will leave my guitar in a corner and let me die.

Violeta Parra in Violeta Went to Heaven

Violeta Parra didn’t “start” at the Louvre. It was one stop on her long path, closer to the end of it than the beginning, and all in all, perhaps furthest from her heart. She may have been the first Latin American artist — and the first woman — to exhibit there, but she started out in the foothills of the Andes, in a village of southern Chile, with parents who both loved music but who gave her a humble life in rural poverty, especially after her hard-drinking father died and left the family in dire misery. Little Violeta became a largely self-taught itinerant performer along with her sister, traveling as a singer with the circus as she grew a bit older, but often she traversed her long country alone or with her children. She collected and transcribed the region’s traditional songs, composed comparable but original music and lyrics herself, toured internationally, wrote about the folk culture of the “southern cone,” programmed it for the radio, and went on to write poetry and create embroidered burlap tapestries, ceramics, and oil paintings that further expressed the experience and legacy of indigenous and mestizo Chileans who shared her history.

Marginalized from the middle and upper classes, city life, and the elite who were educated privately and abroad, she identified with campesinos and miners from the countryside rather than the consumer culture imposed by North America and Europe. From native soil she grew into an icon for Chile’s liberation from modern Western cooptation and neocolonial dominance, and as such, she was considered the mother of nueva canción, Chile’s own music “of the people.” “Create from what there is,” was her motto, and she contributed more than 3,000 songs and other works of art to what became a national archive. Some twenty of those songs are featured in the first theatrical film about Violeta Parra, by the same director who gave us the poignantly political and lyrical Loco Fever and Machuca, Andrés Wood. Those who normally don’t stick around for the end credits of films will miss a special composition by the singer as Violeta Went to Heaven closes — what is considered by many to be Chile’s second national anthem, the ironically celebratory song, “Gracias a la vida” (“Here’s to Life”).

No one from Andrés Wood’s cast or

crew was there to hear it, but a diverse local audience clapped vociferously as

the credits rolled at the end of Violeta

Went to Heaven in Los Angeles — a small audience, like the one on the

screen that applauded at the end of Violeta’s final performance, people who were

surprised and deeply moved. “But it was

so sad,” our North Americans murmured as they left the tiny art-house

projection, as if sadness were not a part of life, as if it were not a defining

component of beauty. For what the film

has on offer is nothing less than a treasure trove of beauty, and we are hard-pressed

to say what shines more in any given moment — the unique gift of the

protagonist Violeta Parra’s poetry and song, the astonishing performance (both acting

and singing) of the lead actress Francisca Gavilán, the yet again striking cinematography

of Miguel Ioan Littín, the strident editing by Andrea Chignoli, or, before and

after all, the ingenious multi-layered screenwriting of Eliseo Altunaga,

Rodrigo Bazaes, and Guillermo Calderón along with co-writer and director Andrés

Wood, who departs here from his previous superb work by basing this strongly

lyrical film on the biography of Violeta Parra written by her son, Ángel Parra,

who served as Wood’s creative advisor as well.

This is all a mouthful. Well, Violeta Went to Heaven is an earful and

an eyeful! It deserves more than praise

for the individual talents creating it and more than seven days in a small

art-house theater; but on another level, it also feels as if it will be around

for a long time. Thanks to Cinema Tropical in promoting the film and to Kino Lorber for releasing it.

How to navigate the torrent of

emotions that is Violeta Parra, someone who straddled continents and centuries

via her research and presentations and yet somehow drew deeply and even

strictly from her own life and identity?

Andrés Wood has chosen to show her subjectivity. In many ways as fearless as the film’s

namesake, he is bravely lush and inventive while never veering from the earth,

the fauna, the vast skies that endow her spirit, and especially from the people

who spur her imaginative powers. Wood

and his longtime visual collaborator Miguel Ioan Littín are the most agile of

poets in pinning down personal moments in this international icon’s life

without ever compromising the pacing or atmosphere in the film.

Cues for structuring the film seem to arrive intact from Violeta Parra: the work as a whole is never a linear narrative but rather a series of discrete episodes, quiet bursts of emotion that evoke others, that dovetail and double back on each other, songs that lead us to images as testimony, impressions that linger as they come full circle. It’s the interior point of view of Violeta, and as contradictory as it may be, and often painful to experience, it registers as authentic and valid.

When asked for advice for young artists, she replies, “They should write what they want, in the rhythms they want. Experiment with different instruments. Sit down at the piano and destroy the metrics! Shout, don’t sing. Blow on a guitar and strum a trumpet. Hate mathematics and embrace chaos. Creation is a bird without a flight plan. It never flies in a straight line.”

American woman who revived her country’s artifacts and folklore in her art and her personal life — Paul Leduc’s Frida Kahlo: Naturaleza vida — indelible moments, shards of a life, envelope the screen intermittently as anachronous fragments, exploding with meaning in a rhythm of their own.

Yes, sound evokes images, but we are endlessly surprised by what we see in Wood’s film, and when we see it. An off-screen creaking followed by flapping in the wind introduces us to the landscape that is Violeta’s, and though these omens haunt the entire film, we don’t see their images until the end, when their meaning suddenly billows with emotion. What does appear at the opening, after a black screen with the mysterious voice of a woman calling out to a girl, is an extreme close-up of a human eye, the face lying on its side and the eye staring at us in silence. It doesn’t move. Only the camera moves, and hardly, holding its focus the way it did in an iconic portrait of Ché Guevarra — of his corpse. As fog finds its way over tree-covered slopes, the camera tracks a guitar moving through the woods with the swishing of a woman’s peasant dress and the crunching of her feet over twigs as she strides.

We might expect Violeta Parra’s music to carry the film, and it does, but not without silence. Ominous sounds emit from her silence. “Sound evokes images,” Sokurov has reminded us, and here that modus operandi is employed even more dangerously than it has been by Sokurov or his mentor, Tarkovsky, in a “biography” of a painter, Andrei Roublev, and a subsequent auto-exploration of a poet and filmmaker, The Mirror. Neither auteur finds narrative a relevant means for sharing the world of an artist of any pursuit. Rather, as in another film taking up the life of a Latin

The garish voice of a male television host intrudes on this space with a strangely re-imagined clip of a woman on a live talk-show: Violeta Parra, as she walks past a TV monitor, with her mediated image in black and white, to the stage for an interview. From this disruption, the camera returns us to a wide shot of the hillside, where a girl stains her mouth eating fresh berries and the woman falls to the ground and is camouflaged by the earth and the fog. Extreme close-ups then alternate between two winged creatures, a red-eyed hen and a yellow-eyed vulture, who peer at her and at us as if in reaction to the fallen body. A boy sits on a case he carries, his hands drumming it as he gazes over the vast mountains until he notices the woman lying in the pebbles. She feigns death and he shakes a smile out of her. When he tells her that her stunt was neither funny nor original, she quips, “You won’t grow old with that humor, my son!”

The film’s title appears on the screen, and we don’t know yet that we’ve already discovered the key motifs of the work as a whole. The boy is Ángel Parra, who lives to tell Violeta’s tale first-hand. The girl is two at once, his sister, María Luisa, and their mother, Violeta as a child. The TV monitor sets up Violeta Parra’s international stature and an identity that is often distorted by the media and the art worlds. And the two birds, motifs of Chilean folk culture, are images that conjure an infinite turbulence of intimacy and conflict in Violeta’s emotional life. It’s not the first time she teases about death. She fakes it on a lonely European street when her miffed lover walks away, but she doesn’t win his attention. She pretends it in her own bed when the town mayor arrives in her last Chilean home, an expansive tent on a plateau above La Reina where she has set up her “university of folk lore,” and her daughter tells him, “She’s dead.”

This stunt is part of a running motif of Violeta’s resistance to behavior she can’t condone. As a girl she protests her father’s singing flirtation in a tavern by literally silencing his guitar strings with her hand. Later she does it by banging his guitar on the piano. To denounce a museum host for sending her to “the kitchen” to be fed when she has just performed as the guest of honor in the Louvre for a bourgeois crowd that proceeds to the dining hall for a banquet, she makes a scene of her exit, spewing, “Deaf! Deaf! Deaf!” into the faces of each in the crowd. When a TV interviewer leads with, “I didn’t know your work was at such a high level,” she retorts, “Well I did, and that’s why I took it there, and that’s why they accepted it.”

This fictional series of interviews is one framework in which Violeta’s life unfolds before us. Edited neither as flashbacks nor flash-forwards but in a scheme that traces Violeta’s emotional trajectory in her singular world view, it is juxtaposed with the framework of her actual domestic life. She often neglects her own children much as her father neglected her, though he is seen teaching music to a classroom of children, including his own, when he is not terrorizing them with his drunken violence. A third framework of the film is the natural environment of the folk lore Violeta researches. From this terrain arrives a Swiss man, Gilbert Favre, younger than she is, a flautist who is as interested in the indigenous music of the region as in Violeta and who becomes her companion. Though they create and perform and travel together, in Paris she tells the curator at the Louvre that what Gilbert does is make her frames. She struggles to maintain a relationship with Gilbert, and his figure provides just the right level of ambiguity to let us wonder about Violeta’s desires in relation to her own tempestuous personality.

travel as they fall in love — yet with a twist that undercuts it from the outset. This irony is due to the lyrics of the song, which she actually wrote quite some time after their budding romance, but which Andrés Wood uncannily inserts exactly as Violeta unleashes her desire for the man. Again, sound precipitates images: as the song is sung (off-screen), the scenes we see show joyous fidelity, all the while the song’s lyrics wryly point elsewhere.

This boldness in Wood’s writing and editing —

whether in scripting the dialogue of the TV talks or in using Violeta Parra’s

lyrics as foreshadowing counterpoints — bravely endows her with a sixth sense,

but one that devastates her. It sets her

apart from the celebrity world and her domestic world, situating her in nature,

but somewhat mythically. For us to take in all these realms together is a

heady, somewhat surreal experience, and one not easily forgotten. The same sensation can be felt in her songs.

B/W photos are all of Violeta Parra

“What is love,” the TV interlocutor pounces, in his usual snide tone. And Violeta: “I don’t really know what love is. I can talk about making an effort, about work. The rest is nothing but butterflies, a passing happiness. Everything that isn’t work is like getting dressed-up for a party just to be ugly again the next day.”

Her passions, expressed either in her music or her spoken voice, not only lay the ground for the films’s scenes, but they are miles ahead. This strategy for presenting Violeta is never more piercing than in her song, “El gavilán,” which motivates a romantic sequence between Violeta and Gilbert — shared creativity, home movies he makes of her, a montage of their European

“El gavilán” (“The Sparrowhawk”) moves with broken words, repeated syllables uttered haltingly to its counter-rhythms. It taunts. It warns. We all but swim in Violeta Parra’s compositions as their chanted melodies engulf us in the contradictions that make the woman, and a song like “El gavilán” hits us as a lover’s wrath, a poor mestizo’s lament, and a nation’s or a woman’s rebellion at once. “Run Run se fue pa’l norte” (“Run Run Went to the North”) also registers simultaneously as a diary entry and an economic critique. The same can be said of “Gracias a la vida.” Is the song meant to be personal, social, or historical? Is it genuinely grateful and celebratory or sadly ironic? It is Violeta Parra, and maybe that is all that matters.

“Here’s to Life”

by Violeta Parra

Thanks to life, which has given me so much.

It gave me two beams of light, that when opened,

Can perfectly distinguish black from white

And in the sky above, her starry backdrop,

And from within the multitude the one that I love.

Thanks to life, which has given me so much.

It gave me an ear that, in all of its width

Records— night and day—crickets and canaries,

Hammers and turbines and bricks and storms,

And the tender voice of my beloved.

Thanks to life, which has given me so much.

It gave me sound and the alphabet.

With them the words that I think and declare:

"Mother," "Friend," "Brother" and the light

shining.

The route of the soul from which comes love.

Thanks to life, which has given me so much.

It gave me the ability to walk with my tired feet.

With them I have traversed cities and puddles

Valleys and deserts, mountains and plains.

And your house, your street and your patio.

Thanks to life, which has given me so much.

It gave me a heart, that causes my frame to shudder,

When I see the fruit of the human brain,

When I see good so far from bad,

When I see within the clarity of your eyes...

Thanks to life, which has given me so much.

It gave me laughter and it gave me longing.

With them I distinguish happiness and pain—

The two materials from which my songs are formed,

And your song, as well, which is the same song.

And everyone's song, which is my very song.

Thanks to life

Thanks to life

Thanks to life

Thanks to life.

“Gracias a la vida”

by Violeta Parra

Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto

Me dio dos luceros que cuando los abro

Perfecto distingo lo negro del

blanco

Y en el alto cielo su fondo estrellado

Y en las multitudes el hombre que yo amo.

Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto.

Me ha dado el oído que, en todo su ancho,

Graba noche y día grillos y canarios;

Martillos, turbinas, ladridos, chubascos,

Y la voz tan tierna de mi bien amado.

Me ha dado el sonido y el abedecedario

Con él las palabras que pienso y declaro

Madre amigo hermano y luz alumbrando,

La ruta del alma del que estoy amando.

Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto

Me ha dado la marcha de mis pies cansados

Con ellos anduve ciudades y charcos,

Playas y desiertos montañas y llanos

Y la casa tuya, tu calle y tu patio.

Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto

Me dio el corazón que agita su marco

Cuando miro el fruto del cerebro humano,

Cuando miro al bueno tan lejos del malo,

Cuando miro al fondo de tus ojos claros.

Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto

Me ha dado la risa y me ha dado el llanto,

Así yo distingo dicha de quebranto

Los dos materiales que forman mi canto

Y el canto de ustedes que es el mismo canto

Y el canto de todos que es mi propio canto.

Gracias a la vida

Gracias a la vida

Gracias a la vida

Gracias a la vida.

Violeta Went to Heaven

Director: Andrés Wood; Producer: Alejandra Garcia; Screenplay: Eliseo Altunaga, Rodrigo Bazaes, Guillermo Calderón, Andrés Wood; Cinematographer: Miguel Ioan Littín (aec); Editor: Andrea Chignoli; Sound Design: Miguel Hormazábal; Music: Violeta Parra; Production Designer: Rodrigo Bazaes; Costume Designer: Pamela Chamorro.

Cast: Francisca Gavilán, Cristián Quevedo, Thomas Durand, Luis Machín, Gabriela Aguilera, Roberto Farías, Patricio Ossa, Stephania Barbagelata, Marcial Tagle, Jorge López, Roxana Naranjo, Francisca Durán, Guiselle Morales, Juan Quezada, Sergio Piña, Sonia Vidal, Ana Fuentes, Pablo Costabal, Juan Alfaro, Pedro Salinas, Daniel Antivilo, Eduardo Burlé.

Color/B&W, 35mm, 110 min. In Spanish, French, and Polish with English subtitles.