So Yong Kim’s Treeless Mountain:

Verses in Time

By Diane Sippl

It’s always astonishing when a quiet film lingers. Of the thirteen films showcased in the International Features section of the 24th Santa Barbara International Film Festival (January 22 to February 1, 2009), there is hardly a more striking one to illuminate the gifts that Asian Americans bring to the art of cinema today than So Yong Kim's priceless and unforgettable Treeless Mountain.

In this cinematic picture-book of untimely rhymes — separate sequences in composition and tone that nonetheless echo each other — writer-director-editor Kim does more than turn the pages of her own childhood; peeling away layers of her early life, she lends these memories a genuine if imaginary little-girl point of view. It’s one thing to have experienced the traumas and trials and small hopes of girlhood with indelible wounds; but it is quite another to create them anew with the acute beauty Kim mines from them. Tender, painful, lyrical, above all intimate, Treeless Mountain is a pearl of poetic naturalism that accrues its luminosity from one hushed sigh to the next.

Kim’s second feature is closer to the Dardenne brothers’ Rosetta, with that film's mysterious scenes of quietude and solitude as its teenage lead tends to her alcoholic mother and then to herself, than to Jacques Doillon’s Ponette, for which four-year-old Victoire Thivisol won the Best Actress award at the 1996 Venice Film Festival for portraying a girl left behind by her abruptly deceased mother. Forlorn and confused as she is, Ponette is surrounded by dozens of classmates with plenty to say to her and also with affectionate adults, including a sensitive and articulate father, to cushion her blow and help her sort out the sudden absence that death brings.

Akin to Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Nobody Knows and Lance Hammer’s Ballast in story and style,

respectively, Treeless Mountain

proceeds with little dialogue but astute attention to the unconscious quirks of

a girl’s grimace or downward glance, her resistant eyes on a vanishing

caretaker, her busy hands threading grasshoppers on a skewer over a grill, her

glowing pride dropping coins into a piggy bank.

“When it’s full, I’ll return,” their mother tells the two sisters, four

and six years old, upon her departure.

But their life is about more than waiting, especially from season to

season as their mother goes after a father whose only presence is a

long-distance phone voice that’s breaking up.

It’s quite amazing to realize, as time passes, that the girls have been taking care of their own physical needs (as if to buffer their emotional loss) in the face of a negligent aunt in whose home they are deposited before she finds them a nuisance, given her drinking habit. Parallel scenes of bed-wetting establish the differences between the mother and her sister-in-law, the mother discreet and soothing (“We’ll keep this just between us; go sleep on my side of the bed”) and Big Aunt requiring the girls to launder their own linens. Likewise, parallel scenes of the girls asking for needed clothes show the difference between the aunt and the grandmother, at whose farm they end up though they’ve never quite met. It might be a sign of coming of age, albeit all too soon, that the little girls, having finally warmed up to an adult after sessions with their granny roasting yams on the open the fire and making dumplings at her table, come to offer her their “life savings” without a thought. The coins in their piggy bank might be enough to buy her a new pair of shoes….

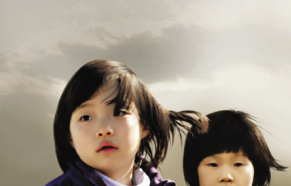

Successfully casting her two young leads, Jin (Hee Yeon Kim) and Bin (Song Hee Kim), from South Korea’s kindergartens and orphanages, Kim then shot the film at three distinct locations: in Seoul City, in Hunghae, the town just north of Pusan where she was born, and at a near-by farm. As with separate verses in a song, with each landscape, the girls enter another state of mind. The film’s pristinely evocative production sound would render a score excessive — synthetic, extraneous, and most likely sentimental, so the only music we hear is two songs the girls sing while playing.

Anne Misawa’s non-obtrusive camera captures the world at the eye-level of the girls, with all their unpredictable movement but also their vulnerable position and limited point of view. On the rare occasion that it pans to their mother early on in the film or their grandmother later, presenting the middle ground of family life, the affection builds in the frame, at least for that assured moment. In general, the emotions are tenuous, but not in anticipation of narrative resolution; that would be anachronistic in Kim’s forward-thinking, free-falling modus operandi. An image opens and fills the screen, a moment suspended rather than a story told. The farm’s meadows and fields expand the view, from the intimate close-ups of the girls atop a dirt mound in the village where they might have spotted a bus returning their mom, to reeds blowing in the autumn sun and clouds passing in the sky. Ultimately Jin and Bin have moved, somehow, through life, through each other, and through time.

While Jacques Doillon was accustomed to interacting with preschoolers and found it useful to conduct workshops for both his own screenwriting research and for practice with the children in making Ponette, it seemed the best plan for shooting Treeless Mountain was to feed the girls lines and directions moment by moment, without them knowing about the scenes ahead of time, and in fact using the script simply as a blueprint, allowing for their spontaneity. Instructing five-year-old Song Hee Kim and seven-year-old Hee Yeon Kim (neither any relation to So Yong Kim) to repeat the lines she was telling them without looking at either her or the camera and without leaving the set ‘til she called the word “Cut!”, the director laid out these rules as if the girls were playing a game and could score points. Then she co-edited the forty-plus hours of footage with one of her co-producers, Bradley Rust Gray (her husband and fellow filmmaker) so as to remove her own guiding voice from the footage.

Though the film is not an

autobiography, it is inspired by the first twelve years of So Yong Kim’s life,

before she left

Treeless Mountain

Director: So Yong Kim; Producers: Bradley Rust Gray, Ben Howe, Lars Knudsen, Jay Van Hoy, So Yong Kim; Screenplay: So Yong Kim; Cinematography: Anne Misawa; Sound: Eric Offin/Tandem Sound; Editors: So Yong Kim, Bradley Rust Gray; Original Score: Asobi Seksu; Design: See Hee Kim

Cast: Hee Yeon Kim, Song Hee Kim, Soo Ah Lee, Mi

Hyang Kim,

Color, Super 16 to 35mm, 89 minutes. In Korean with English subtitles.