4-12-13

Three Worlds at COL-COA

By Diane Sippl

Raphaël Personnaz as Al, Arta Dobroshi as Vera, and Clotilde Hesme as Juliette in Catherine Corsini’s Three Worlds

From April 15-22, 2013 at the Directors Guild in Los Angeles, the 17th Annual City of Lights, City of Angels, known to Angelenos as COL-COA, will present 38 feature films and 19 new shorts with at least 9 of the participating writers, directors, actors and producers on hand to discuss their work. In two adjacent theaters nicknamed the “Truffaut” and the “Renoir” just for this week of French film premieres in Hollywood, this year for the first time, audiences will also be able to see and celebrate films made abroad yet produced by French companies, all with English sub-titles.

Over the last years the mission of this enormous event has become increasingly clear: to shine a broader and brighter light on French talent, industry output, and business potential that can facilitate commerce across the national borders. Hollywood movie-makers wearing every hat, along with distributors, publicists, and members of the press, will come to be surprised and entertained, hopefully impressed with films that can make a contribution to their own work. ELMA (European Languages and Movies in America) will bring youths as well, to high school screenings, a Master Class, and a student screening. And then there are the Francophiles, French and American alike, who’ll come to get in touch with the culture. There will even be those, as often happened in the early days of COL-COA, who will look for the stock-in-trade sophistication and nuance, the social critique, the special French sensibility and style, the tasteful innovation, that long ago put the culture’s cinema on the map and, in many ways, made Paris the film center of the world.

In this last category, this year’s line-up should not let anybody down if the ticket purchase starts with a particular mid-day segment of the festival, “COL-COA Classics.” To see Sandrine Bonnaire’s film debut in Maurice Pialat’s To Our Loves (France’s Best Picture César for 1983) in which he plays the teenage girl’s father would put anyone in the mood for a week of French cinema. The Fire Within, made twenty years earlier by Louis Malle with Jeanne Moreau, not only brings Pierre Drieu la Rochelle’s novel to the screen but also shows the legacy of French cinema in inspiring new international talent: Joachim Trier recently created his version of the same work in the piercing Oslo, August 31st. One new treat in COL-COA this year is Alain Resnais’ You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet (which will be reviewed separately by this author), a masterful return to the themes of his earlier films with striking new flair. Fans can see Jean-Paul Belmondo and Gérard Depardieu in Resnais’ Stavisky (1974) to get another glimpse of this auteur’s unconventional aesthetic in probing memory, history, and imagination. Jeanne Moreau pops up again in Jacques Demy’s atmospheric Bay of Angels (1963) accompanied by Michel Legrand’s impossibly romantic score, delivering us to a sultry underworld in the South of France. And by now, André Téchiné joins this roster of “old masters”; with all the re-makes of Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights in recent years, we can see his behind-the-scenes take on a houseful of budding writers using masculine pen-names in The Brontë Sisters played by Isabelle Adjani, Marie-France Pisier, and Isabelle Huppert, no less, along with brother Pascal Greggory in his downward spiral as the sisters rise (and fall).

The femmes bring us to another aspect of the festival this year, the work of women behind the camera as well as in front of it. Director Danièl Thompson’s It Happened in Saint-Tropez provides the opening gala of COL-COA with a domestic comedy she co-wrote with her son, Christopher, and via its two male leads, it takes audiences back to two previous COL-COA block-busters, Gainsbourg (starring Eric Elmosnino) and Welcome to the Sticks (featuring Kad Merad). Starting out as a screenwriter with credits such as Cousin cousine (1975), Queen Margot (1994), and Those Who Love Me Can Take the Train (1998), Danièl Thompson began directing with La bûche, followed by Avenue Montaigne, which brought her to COL-COA in 2006.

Catherine Corsini also found her

breakthrough in screenwriting, having arrived in Paris at age 18 to study acting. Neither of these talents are lost in her as a

director of 15 feature films as of today with actresses such as Emmanuelle

Béart and Jane Birkin. Her recent film, Three Worlds, marks the second time she

has been to Cannes,

this time competing in the Un Certain Regard section in 2012. Having shown at ten festivals, the film will

now be distributed in the U.S. by Film Movement.

This article will spotlight Three Worlds for two good reasons, plain and simple — its writing and its acting. Three Worlds has been slated in COL-COA’s film noir series, a long-time popular segment of the festival based on a genre that has always bounced back and forth between Paris and Hollywood. The film has been neatly labeled a “thriller,” a “crime movie,” and an “action picture” throughout the literature promoting it. Its setting at a car dealership, its opening sequence of an updated game of “chicken” played on the hood of a car at night by three male cronies who are drunk and up to no good, and its continual demanding and counting and passing of money, in envelopes from hand to hand, surreptitiously and illegally, all mark it with the shadowy behavior of an underworld, but no more than the Dardennes depict Lorna’s Silence as “noir.” Corsini’s protagonist may be a self-made man moving up in a corrupt world that sucks him back into it when he would leave it, but no more than Dostoevsky’s anti-hero in Crime and Punishment. And most significant, if Corsini’s female leads are femmes fatales, it would be interesting to see what upstanding women would think and do. And maybe that’s just the point — aren’t we all “on the verge…”?

Catherine Corsini’s writing is not simply about craft, and much less about genre. Often enough, she lets us know she has something else in mind beyond mise-en-scène and machinations of plot and the salty, clipped dialogue that characterizes many a film noir classic. “Characters have to make moral choices,” she tells us. “With this movie, I decided to go in this direction: characters’ choices belong to a physical dimension, as in the first scene, but then they acquire an intellectual dimension as well.” She refers to an event very early on that brings three 30-year-olds — Al, Juliette, and Vera — from entirely separate social spheres, into a collision with each other with utterly irretrievable consequences. Al, a businessman on the rise, becomes a hit-and-run driver; Vera’s husband is the victim, and Juliette is a witness. Al is poised to marry his boss’ daughter and take over his flourishing business, racketeering and all; Juliette, educated and reflective, is uncomfortable in her own skin; and Vera, who hoped she had everything to gain as a Moldavian émigré, legal or not, now has everything to lose.

Corsini shows us the Three Worlds of Austrian philosopher Karl Popper: material, emotional, and mental. The first is physical and biological; the second, contradictoryand problematic; the third, theoretical, mythical, social — a site of learning. They interact with and impinge upon each other as three tiers of fallout: actions, feelings, consciousness; or put another way, morals that produce guilt and beg courage.

The progression lies within the

characters themselves. Any external

factors — police, judges, social workers, family, fiancés, lovers — hover in the

“night” but never determine an outcome.

It’s the characters who recognize or imagine or, hand-over-fist, produce

their own consequences, despite themselves and sometimes, surprising themselves. Corsini sums up

her film:

“The whole world is on watch, and all the moral questions keep

shifting from one character to the other, without them being able to get rid of

their burdens.”

They certainly try, and generally, in terms of money. How much does a mistake cost — a physical violation, a moral choice, regret, sorrow, repentance, compensation — how do we monetize reversals of a way of life, the bodies and minds of providers and soul mates, losses of the human heart? In several quiet scenes we see Juliette’s fiancé, a philosophy professor, reading De Certeau at home or lecturing on Heidigger, to the effect that while we can help each other a lot in this world, there is one thing no one can do for someone else, and that is dying. Dying is our autonomous right, our solitude, ours to do alone.

Listening in on his talk is Juliette, pregnant, and on the way to becoming a doctor — ironies never stated as such but viscerally felt. What she hears and feels, thinks and does, are all of a piece, regardless of what we may register as surprises and contradictions. Unlike the tacit Juliette, Vera is direct, overt, straight as an arrow. She has needs, and she voices them without filters, and she takes without misgivings. It’s a survival mode, and she’s known it a long time.

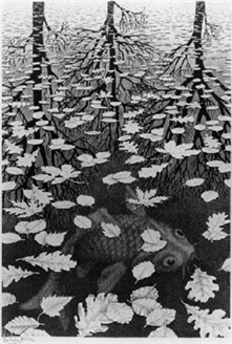

Al (Raphaël Personnaz) is the pivotal character; he’s

where it all started, and he’s the one in a position to change. At any given moment in the film, Corsini’s

perspective on him, and therefore ours, is threefold, as if in the Three Worlds of M.C. Escher’s

lithograph. Al swims in the world below,

but the surface and the world above are present in the frame. Reflection and refraction are in constant

interplay in Corsini’s writing. The same

can be observed in the casting and acting.

It’s easy to relate to Personnaz as a Raskolnikov after seeing his recent performance as Count Vronsky in Joe Wright’s Anna Karenina. More to the point, his schismatic character may have started out as, quite literally, “an accident waiting to happen,” but before our eyes he emerges as a “person ready to be formed.” It’s a rare joy to see it, and he inhabits the role impeccably.

Yet leave it to Catherine Corsini to give us two female leads who are quite unforgettable. Arta Dobroshi as Vera is the mature reincarnation of Lorna in the exquisite Dardennes film, Lorna’s Silence. She is once again sumptuous, virile, and imposing. As for Clotilde Hesme (who plays Juliette), she is ever radiant, from Philippe Garrel’s Regular Lovers to Eric Guirado’s The Grocer’s Son to Alix Delaporte's Angel and Tony at COL-COA 2011. Increasingly bright, curious, reflective, inventive, compassionate, and self-willed, she keeps us guessing, thinking, and admiring. Some femme fatale!

Catherine Corsini, Co-Writer/Director of Three Worlds

Three Worlds

Director: Catherine Corsini; Producer: Fabienne Vonier; Screenplay: Catherine Corsini and Benoît Graffin; Cinematographer: Claire Mathon; Editor: Muriel Breton; Sound: Yves-Marie Omnes, Benoît Hillebrant, Olivier Dô Hùu; Composer: Sune Martin; Original Score: Grégoire Hetzel; Set: Mathieu Menut; costumes: Anne Schotte.

Cast: Raphaël Personnaz, Clotilde Hesme, Arta Dobroshi, Reda Kateb, Alban Aumard, Adèle Haenel, Jean-Pierre Malo, Laurent Capelluto, Rasha Bukvic.

Color, 35mm Scope, 101 min. In French and Moldovan with English subtitles.