8-22-18

The Third Murder: Kore-eda’s Truth in Packaging

By Diane Sippl

“In our time, the fantastic belongs only in the madhouse, not in literature, and should be left to the charge of doctors, not writers.”

Literary critic Vissarion Belinsky in reviewing The Double by Fyodor Dostoevsky, 1846

“Psychiatry isn’t science. It’s fiction.”

Akihisa Shigemori in The Third Murder

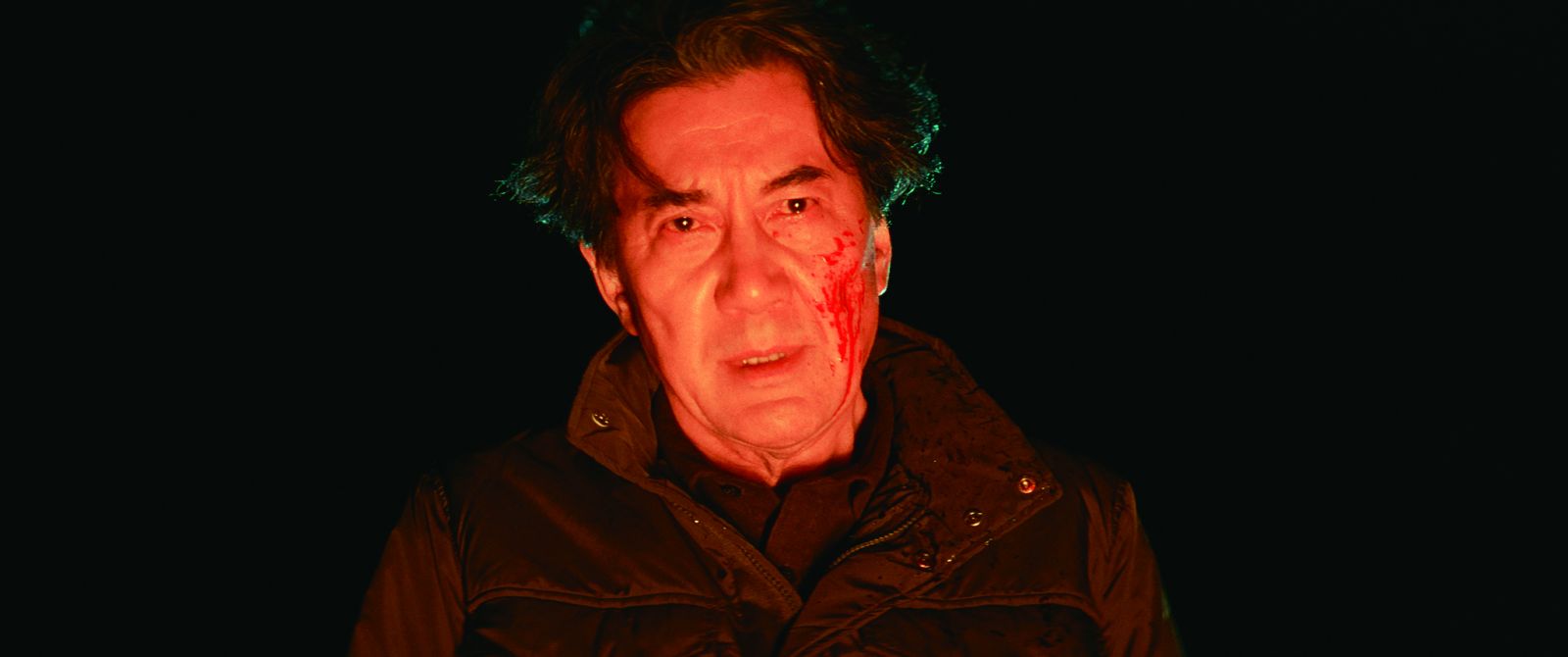

Two men walk toward a riverbank in the dark of night, one clubs the other hard enough for him to fall over and die, and then the attacker sets fire to the corpse. Upon his arrest, that same man, Takashi Misumi, confesses to committing the crime. He has robbed the man as well. Because he has already been in prison for murder, if convicted this time, he will face the death penalty. An earnest young attorney, Tomoaki Shigemori, takes up the case and tries to reduce the charges, just as his father, Akihisa Shigemori, did for that client’s defense in the initial court case three decades earlier, back in the day when a condemning socio-economic environment counted as extenuating circumstances relating to crime.

The title of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s recent film, The Third Murder, gives us his theme right off. That title would be a good place to start in the conversation among viewers as they leave the theater. The storyline is incessantly ambiguous and keeps us guessing throughout what appears to be a who-done-it that morphs into a courtroom drama. We’re okay with the mysteries, but when the film culminates not with answers but with questions, do we feel short-changed? Hardly.

“No one here tells the truth,” comments a teenage girl near the end of the film, and her observation extends far beyond those called as witnesses. Still, The Third Murder is no Rashomon, though it might also remind us of Kurosawa’s early crime dramas in its interrogation of marginal existence as a determining social force and of his later epics such as Dersu Uzala in its respect for the mystical in life. Yet in this case, rather than “mystical,” the word “spiritual” aptly applies, in a fairly non-denominational and mundane way—the spirituality we see in Crime and Punishment or The Brothers Karamazov or The Idiot—a kind of blind persistence in aspiring to goodness and the guilt in failing to perform it. Then again, there is nothing blind in The Third Murder. All is observable, knowable, connected, and often strategically “overlooked.” Hence when, at the end of their encounter, Shigemori, the defense attorney, asks Misumi, his client, “Are you really just a vessel?” and the accused replies, “Are you asking me that? What’s a vessel?” we are quite content with no answer, just as a 14-year-old girl’s question, “Who decides who gets judged?” moments earlier, is a perfectly adequate resolution for the film.

It’s the way in which The Third Murder engages us that matters. It could be argued that, for all the dialogue in the office banter, interviews, and testimony, the purpose and success of the film derive, for the most part, from the camera and editing. In this way, Kore-eda is truly a master of cinema. Here he has not only written the original story and screenplay for his film, but he, the director, has edited it as well. The delivery of the visual language in this seemingly verbal film is taut and brilliant. The male leads, attorney and client, move closer and closer to each other, eventually face-to-face in numerous close-ups with eye-line matches within the frame but finally with their heads superimposed on each other, all but totally, facing the same direction. It’s the perfect denouement for a film peppered with imaginary, non-verbal, point-of-view sequences in which one man enters the other’s turf, not physically but mentally or emotionally, to astounding effect. Dostoevsky’s The Double comes easily to mind, the client a symbolic doppelganger stalking his attorney’s psyche.

Do some people deserve not to be born? Then does the death penalty suffice in punishing them? Does it get people to face their crimes—to accept responsibility for them? These are questions raised overtly in the film’s dialogue, as repeatedly as reflections on the prison visitor’s window haunt the attorney’s conscience and consciousness and our own. But other queries arise and linger, in regard to the relativity of truth and the morality of deceit, just as the camera frames a man (it’s a point of view shot from above, but it could be either the attorney’s or the client’s) at a crossroads, a snowy intersection by a river—a cold and lonely place where two hearts and minds meet as life flows independently along its course.

“Psychiatry isn’t science. It’s fiction.”

The landscape of the face is captivating in this film as well, and we cannot ignore it. A young woman, a daughter, might also have visited the scene of the crime, whether that space be physical or psychological or spiritual. Her face, always relevant, looms large in significance as the film gets to the core of the matter, the central theme—the third murder. That face—of the daughter of the deceased—is hardly distinguishable from the face of the defense attorney’s daughter; and either of those faces could be replacing the face of the defendant’s daughter in a surreal scene the attorney imagines of a snowy day in Hokkaido. A wide, aerial shot shows both men, between them a girl, all lying prone, face up, ready to make “angels” in the snow (they also could have been “crucified” or just be the floating dead of another world). Three young women surface in the story in one way or another, yet we hardly know them, and at least two of them “seem to lie a lot.”

The defendant’s last prison sentence was for killing two loan sharks, stealing their money, and burning their apartment; so technically, if we are to assume he was guilty of those crimes and also of the one to which he has just confessed, then the latter is his third murder. But if we consider it the second time he is being charged and the second verdict that will be reached for him, “third murder” can take on bigger connotations. That murder, for example, could be of either of two men—Misumi, the defendant who faces the death penalty, or Shigemori, the attorney who was called to take on this case. Clearly the film takes a position on capital punishment, and Shigemori may not be able to admit it (rising practitioner of the Japanese legal system that he is), but he actually doesn’t want Misumi to die. Against his own proclamations, Shigemori is actually buying into an alliance with his client, compelled as he is to discover the man’s point of view. Given the way and the extent to which these two men emerge as doubles, the “third murder” could refer to the death of Shigemori by Misumi, his doppelganger, as little by little, he kills off the old professionalism of the attorney in what often looks like an unjust justice system and leaves him entirely “done in” as to his former world view, to say the least.

Still, the relatively surreal vision of the film hardly allows for such a black-and-white morality; Misumi exists in a realm of his own, one for Shigemori—and us—to ponder. He is not afraid to die and seemingly holds no regrets, having, for all we can surmise, fulfilled two oppositional needs, one in relation to a 14-year-old girl and the other in relation to her mother. When all is said and done, those who refuse to see Kore-eda’s film as other than a crime mystery or a courtroom procedural (as “a departure for him from his family themes”) and therefore refuse to be satisfied with an “unsatisfying plot resolution” are missing the core of human relations—loss, death, memory, legacy—that have driven all his “family films,” from After Life to After the Storm

Lies, cover-ups, withheld back-stories, and duplicity permeate the film; the sand shifts like a devil’s swamp, and the role of deceit itself often becomes dubious. But it’s not so much a matter of who is hiding what or who is covering for whom as it is the work of observation that counts. Can we “see” with our hearts? Is believing the same as understanding, and is one any good without the other? Is compassion enough as a feeling, or does true compassion elicit action, even when it appears unreasonable, counterproductive, or downright delusional? Who is the “idiot”? Who is the “double”? Kore-eda started his career aspiring to become a novelist. Story is paramount for him, but we don’t have to go much further west than Russia—perhaps as far as Turkey or Austria—to see a similar approach to storytelling in Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia and Götz Spielmann’s Revanche. The crimes, the doubles, and the young women affected by the men all come together in ways similar to Kore-eda’s modus operandi in what is surely one of his best works.

“There is no crime and no sin, only hunger and the hungry.”

Such a maxim, uttered by the critic Belinsky, wasn’t good enough for Dostoevsky, who continually probed the question of responsibility for one’s deeds, overturning the premise that one can escape one’s guilt for actions taken. In his second novel, The Double, he dropped his writer’s quest for compassion and headed straight for the human psyche, showing us the world through the eyes of a madman and not always revealing his author’s point of view on that character. The man, Golyadkin, is an oppressed civil servant, a victim of state bureaucracy who is already a Titular Councillor but is afraid of losing favor with his superiors and represses his angst. Yet his vanity as a social climber comes to haunt him, just as it does Shigemori, Jr. all the while he takes on Misumi as a client under the shadow of not only his senior colleague but also his father, who is now retired from the legal profession but is no less a daunting figure for the young attorney who is failing utterly in his own family. Like Golyadkin, Shigemori would like to prove himself a success but feels more and more uncomfortable in the role he must play. The balance in both stories shifts; the more the striver fumbles, the more clearly his counterpart emerges as an alter-ego, both face-to-face in the flesh (the film even shows this as hand-against-hand on the pane of the prison visitor’s window) and as a phantom (as in Shigemori’s dream on a train in which he inserts himself into Misumi’s anecdote). The double is a creature of both wish-fulfillment and nightmares.

At first the double is deferential and unassuming, but as he wins the confidence of his “target” and discovers his secrets (in Shigemori’s case, his failing relation with his daughter), the doppelganger finds ways to exploit his prey. For Dostoevsky, the double is the image of the man’s unconscious desire for social prestige and also the guilt it brings him, since Golyadkin can’t assert himself without violating the ethics to which he has subscribed. Likewise, Shigemori is largely responsible for his own murky vision and insidious guilt in pursuing this law case. Given all the repetitions (with situational reversals) in the dialogue, the visible reflections, and the refracted points of view—the shifting turf—we begin to ask who has sinned and what makes up a crime.

“The idea is excellent,” Dostoevsky wrote 30 years after The Double was first published, “and I have never contributed anything more significant to literature than this idea. But I was very unlucky with the form of the story.” In some ways Kore-eda’s film is a far cry from The Double, a last vestige of the fantastic in Russian Romanticism, a gothic tale that might seem a distant cousin to the realism of Crime and Punishment; yet Raskolnikov’s very name means “split apart.” Kore-eda has likewise been criticized for the form of his storytelling here, perhaps precisely because what we see on the screen looks very real, assuming we view the film through the eyes of narrative realism. Can we fully assume that the opening scene actually happened as told? And for that matter, is seeing believing? There were no witnesses, we are reminded throughout the film. Regardless, the reports that surface are important enough for us to take stock of them. “It’s an interesting story,” Misumi utters even at the end as Shigemori does his best to configure the causal factors for his client’s motives in what seems the ultimate “contradiction” but may well be Misumi’s clearest strategy yet.

The notion of a “double,” whether in literature or in cinema, is a metaphysical conceit that can be complex, rich, and powerful in the right hands. Its source in folk tales reminds us that the device may derive from instinct, which makes it nonetheless psychological, as Freud would discover in his studies of repression, projection, and displacement. At times in The Third Murder it’s Misumi who resembles Golyadkin, in his humiliations throughout his life and his desire to escape from himself, from the harm he feels he brings to others, to leave this life. But he would like to have served a purpose before he dies, and we are left to determine the nature of it. If Dostoevsky depicts a social anxiety in the split between who one really is and how one is expected to represent oneself, the double, or Misumi, experiences little difficulty with this duality, performing the actions he deems necessary in the society and owning them with integrity, even when he has to lie to do so. Beside him, Shigemori wears a professional and social straitjacket that torments him both as an attorney and as a man. Though he may not look as horror-stricken as the paranoid, delusional Golyadkin, his growing awareness of Misumi’s paradoxical “freedom” leaves him aghast, to say the least.

The Third Murder

Director: Hirokazu Kore-eda; Producers: Kaoru Matsuzaki, Taguchi Hijiri; Original Story and Screenplay: Hirokazu Kore-eda; Cinematographer: Mikiya Takimoto; Editor: Hirokazu Kore-eda; Sound: Kazuhiko Tomita; Music: Ludovico Einaudi; Production Design: Yohei Taneda

Cast: Masaharu Fukuyama, Koji Yakusho, Suzu Hirose, Izumi Matsuoka, Isao Hashizume, Mikako Ichikawa, Shinnosuke Mitsushima.

Color, Cinemascope, 124 min., Japanese with English subtitles.