7-12-14

Small Island, Small World

By Diane Sippl

Day-o, day-o

Daylight come and me wan' go home

“The Banana Boat Song,” Harry Belafonte

We are here because you were there.

Ambalavaner Sivanandan

I like that point of contact between black and white.

The fission. For me, that’s where the energy is.

Andrea Levy

Small Island first came to my attention as a middle-school drama production by early teens in Southern California. With a class-size ensemble dancing to lively Calypso and a sentimental heroine swooning to the drumming of a woodpecker, all staged with colorful costumes and scintillating light, the question had to arise: what are these young hearts learning about the cruel contradictions of history?

In my research prior to the National Theatre’s staging of Small Island in the UK, it became clear that there was ever so much to learn, all highly relevant to today’s news stories of related atrocities. However, I haven’t been able travel to London to view this production running in the grand Olivier Theatre from May 1st-August 10th, which is why I was so pleased to see it turn up at UCLA’s James Bridges Auditorium, a state-of-the-art movie house at the center of the university’s School of Theatre, Film, and Television. It’s a National Theatre Live presentation of the play filmed straight from the London stage. (This series has been broadcasting British theatre from a variety of venues on cinema screens throughout the UK and around the world for a good ten years now.)

Small Island was also produced as a two-part BBC television mini-series in 2009, but its source is a quasi-autobiographical novel by Andrea Levy, who died just months before the National Theatre’s production hit the stage. Published in 2004 and lauded for its panoramic scope of major themes narrated through the intersecting lives of two couples, one Jamaican and one British, Levy’s book has opened the lens on racism and illuminated its intricate connections with class stratification, work, immigration, national policies, and social mores. Andrea Levy made a prescient contribution to the ways we view and challenge, for example, the declarations, practices, and “apologies” of the UK’s Home Office as recently as a week ago.

Andrea Levy sought to show two histories—Caribbean and British—as one, to bring to the fore how inextricably bound together they are, to the point that before, during, and after immigration to the land of their colonizer, many Jamaicans saw themselves not as racial outcasts but as middle-class British citizens who spoke the language, built careers, and served the country just as (or better than) their white neighbors did. The military experience of World War II was undergone without segregation in the armed forces, as there was in the U.S. Post-war recruiting of the work force from Jamaica to England was heavy, to recoup losses of production from the war and fill the labor pool. Invitations from the British Isles to those living in its tropical outposts guaranteed citizenship and promised futures; after all, the Queen was still actually Head of State in Jamaica, then a crown colony.

Andrea Levy’s own mother trained as a teacher in Kingston, and came on a banana boat just six months after her father and uncle arrived on the SS Empire Windrush in 1948 among a thousand others. These men had proudly enlisted in and fought in the RAF to defend their “mother country” during the war. Now they were ready to serve as its workers, to extend their educations, and to build careers and homes; yet they were barred from jobs, housing, places of worship, and social life.

The complexity of Levy’s own ancestry is not uncommon: her paternal grandfather, Jewish, emigrated to Jamaica after WWI and converted to Christianity; her maternal grandfather was a white plantation attorney who had a child with his black housekeeper. Both sides of her family came from mixed races, so her parents saw themselves as immigrants but not racial “others.” On the contrary, Levy focused on the tie that binds—it was her life experience; however, in the UK, that tie was one tangled ball of yarn. Still, Levy never shunned the contradictions of history, but plunged right into them.

The kernel of Small Island’s expansive drama—which encompasses both natural and man-made disasters (a hurricane and a war), the fate of two colonies (of Jamaica and also India), the racism of two nations (the UK and the US), and two marriages of convenience (one between blacks and one between whites)—is a simple lie: the big lie of racial inferiority (when the reality is racial subjugation) that always brings the private and hardly smaller lie of separatism and hatred (when the reality is miscegenation and interracial love). This premise illuminates the second fundamental aphorism of Sri Lankan novelist and theorist Ambalavaner Sivanandan, himself an immigrant to the UK: it’s not that the personal is political, but that the political is personal. The “small island” might seem to be Jamaica, and certainly the UK, as it shrinks in both its political domains and its moral grounds, but might it also be that “love child” who falls between them both—the tie that binds?

Andrea Levy thought of her writing as “trying to make the invisible visible, and to put back into history the people who got left out.” Helen Edmundson’s compelling theatre adaptation of Levy’s novel is a feat in itself, and Rufus Norris’ directing of the three-hour-plus production manages to be both monumental and intimate, following exactly the prescription of its historical order according to Levy (who, it is said, agreed to the commissioning of both these theatre artists before her death). From the casting to the directing of actors to the staging, the result is a work that is utterly immersive. Filling (and not filling, but highlighting) the expanse of the huge stage of the Olivier within the National Theatre complex, the play engulfs us in history, present-day conflict, and emotional catharsis. It feels “epic,” not just in the reach of its themes and scope, but in its theory of theatre—the epic theatre of Bertolt Brecht, who wryly asked, “What happens to the hole when the cheese is gone?”

Brecht’s alienation-effects of epic theatre—sporadic songs sung by the actors, polyphonic and conflicting viewpoints among members of a large ensemble, rear projections of newsreel photos, a dramatic rise and fall of action that is fragmented, intermittent direct address to the audience from the characters, lean and expressionistic sets such as doors and windows, and stairs and ladders layered with meaning—have come to be so commonplace today that we take them for granted; less obvious but more fundamental is Brecht’s political orientation to drama, a very lyrical stance, at that, which is shared by the makers of Small Island: The world can be re-made. To see the contradictions of history—to see through them to the other side—is to see that they are not tenable. The lie falls apart. It is its own undoing.

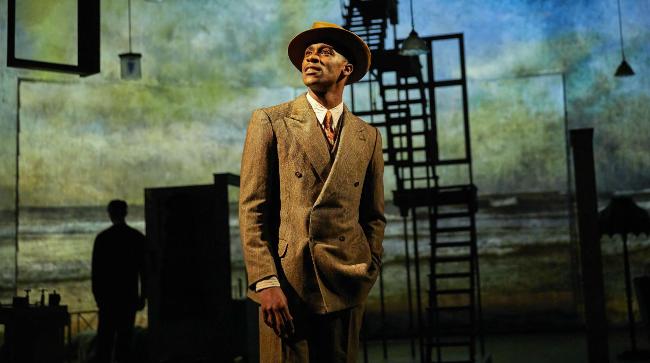

While the play essentially opens by introducing us, on separate but parallel tracks, to the desires of two young women, Hortense in Jamaica and Queenie in England, it’s a gallant young man who spurs the action by leaving Kingston to enlist in the RAF and defend the UK against Hitler. The first to emigrate, Michael sets the trail and the tone, one of ambition and high hopes. In some ways, his counterpart is the white Londoner Bernard, who also enlists, but not until after he manages to marry Queenie and secure a home for her away from her family’s pig farm and also install her as the caretaker of his father, still shell-shocked from World War I. The most blatant racist of them all, Bernard is away defending his homeland in India much of the time, and Michael really only “passes through” London, but long enough to launch the intimate layer of the play’s conflict. For that matter, Queenie and Hortense meet only near the play’s end, in the most devastating and uplifting of climaxes and denouements. There is a pivotal character who connects them, the Jamaican Gilbert, who has also fought in the RAF and seeks a future in London.

Gilbert is a sweet-talking ladies’ man who flies after the heart of Hortense (whom he calls a “spit-fire” for her prim and stern resistance) the way she flies after the heart of Michael (even if only covertly, since she was raised with him as his cousin). When Michael emigrates and Gilbert follows suit, Hortense follows Gilbert, but not until she snatches him as her husband so as to guarantee passage to London after he departs. It’s right to say “snatches” because Hortense betrays and manipulates her best friend Celia to steal Gilbert, her “ticket to ride” even though it is Hortense who has given Gilbert the money to journey to England.

It is then Gilbert whom we follow through the lonely streets of London as he seeks housing, work, and companionship, all in the face of British racism. Queenie, who has seemingly been abandoned by Bernard since the war, has rented rooms from their home and takes Gilbert in as a tenant. All is barely manageable for them until Hortense arrives to live with Gilbert and Bernard returns home after Queenie regarded him “missing in action”; then, nothing seems manageable at all. For one thing, Queenie has a secret—but not for long.

It’s a marvel to see how Gilbert, Hortense, and Queenie all grow and change as characters. Gilbert is by nature cheerful, and through much of the play he carries the role of broad sex-humor, but his postwar grin-and-bear-it façade betrays another dimension. Gilbert has gall. Out of one side of his mouth, when an uneducated Brit asks him if he’s from Africa, he asks the audience, “Why don’t they know anything about their own empire?” Out of the other side, he has at least one nasty, contemptuous sex quip, when racist agitation strikes, that rings honest and true, an ironic Freudian slip, as he taunts his white attackers that they’re just afraid he’s sleeping with their wives.

Queenie is a prime example of the marvel of filmed drama; close-ups reveal her face to be a kaleidoscope of changing emotions that coincide with the fluctuating social landscape of London as immigrants from the colonies make the scene. Beginning with no knowledge of race let alone racism, she runs the gamut of risk-taking with hardly any consciousness of doing so. Her naiveté is mirrored in Hortense who, in juxtaposition, is appalled by the cramped poverty and racial stigmatization she is expected to tolerate in the life she finds with Gilbert. Bernard’s invasion in the room Queenie rents to her is the crowning blow—but there is one more. And Hortense unwittingly accepts it as another level of the play’s Freudian irony sets in.

One fascinating aspect of the writing of Small Island, which the actors truly master and which is echoed in the hollow spaces of the stage, is the holes in their own personal knowledge, the blind spots they would more safely uphold—in other words, all that they deeply suspect but choose to ignore in service of a more promising life. Gilbert knows as well as anyone that there is nothing that can keep a black man from intimacy with a white woman (thus he blindly flings this taunt at his white oppressor). Hortense knows that mothers and daughters abandon each other (thus she condemns Celia who would leave her mentally disabled mother behind). Can Gilbert and Hortense, both jilted lovers in a sense, find a way to build a meaningful life together, one that honors Queenie’s newly gained sensitivity to racism? It’s a big stride, not only politically but personally, for this new Jamaican British couple to create from the “small islands” of their legacies a bond of their own.

In part, it is Queenie who bears the advice of Andrea Levy, who wrote in her novel,

There are some words that once spoken will split the world in two. There would be the life before you breathed them and then the altered life after they'd been said. They take a long time to find, words like that. They make you hesitate. Choose with care. Hold on to them unspoken for as long as you can just so your world will stay intact.

Political oppression notwithstanding, perhaps what looks like personal suppression becomes wisdom and lessons for living in the “small island” of postwar Britain then and now.

Small Island

HD, color, in English

3 hours (plus 20 minutes of brief video presentations taking viewers behind the scenes)

Creative Team

Playwright: Helen Edmundson, based on the novel by Andrea Levy; Director: Rufus Norris; Set and Costume Designer: Katrina Lindsay; Lighting Designer: Paul Anderson; Sound Designer: Ian Dickinson; Composer and Rehearsal Music Director: Benjamin Kwasi Burrell; Projection Designer: John Driscoll; Movement Director: Coral Messam; Fight Director: Kate Waters; Music Consultant: Gary Crosby.

Broadcast Team

Director for Screen: Tony Grech-Smith; Technical Producer: Christopher C. Bretnall; Lighting Director: Bernie Davis; Sound Supervisor: Conrad Fletcher; Script Supervisors: Amanda church, Annie McDougall.

Primary Cast

Leah Harvey, Aisling Loftus, Gershwyn Eustache Jr., C.J. Beckford, Andrew Rothney, Shiloh Coke (in an ensemble of 26 actors appearing on stage playing 40 roles)

A production from National Theatre for the series, National Theatre Live

Presented through L.A. Theatre Works at James Bridges Auditorium, UCLA School of Theatre, Film, and Television, 235 Charles E. Young Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90095, (310) 827-0889. Tickets at:

https://web.ovationtix.com/trs/pr/1008577