2-2-26

Joachim Trier’s Sentimental Value

By Diane Sippl

There is no architect

Can build as the Muse can;

She is skilful to select

Materials for her plan;

Slow and warily to choose

Rafters of immortal pine,

Or cedar incorruptible,

Worthy her design…

She lays her beams in music,

In music every one,

To the cadence of the whirling world

Which dances round the sun—

That so they shall not be displaced

By lapses or by wars,

But for the love of happy souls

Outlive the newest stars.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The House”

“Cinema is architecture in time.”

Andrei Konchalovsky

He’s a director for the big screen who lives to discover the intimacy of the human face; she’s an actress for the stage who thrives in the distant footlights of a dark theater. He looks and searches; she embodies. He’s a gentle giant; she’s a raging rebel. In taste and temperament, they would seem to clash as opposites. Yet renowned and awarded as he is, he’s fading away as a “has-been.” And while she’s basking in her light as a “rising star” in the world of illusion that is her only refuge, it terrifies her. Each needs a safe haven—or better yet, a breeding ground for new energy, a lifeline for creativity, a habitat for growth. Some would call such a place a “home,” and others would recognize it as “art.” It’s owing to Joachim Trier’s lineage that he is able to see it as both. His sixth feature film as a writer and director, Sentimental Value honors the feelings to be forged through both heritage and aesthetics. Trier’s inherent sensitivity and cultivated talents allow him to posit the arts as solid ground for nourishing the inspiration and hope, the understanding and love, that we look for in a family.

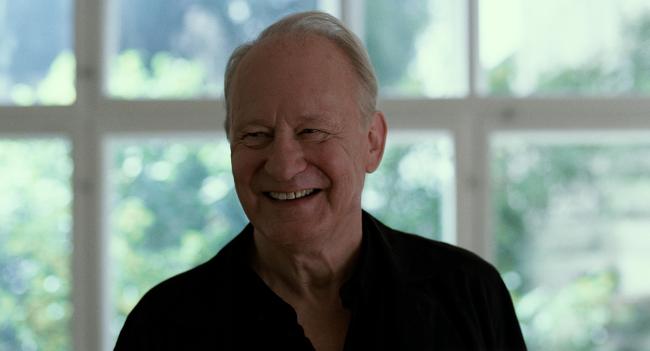

Stellan Skarsgård as Gustav Borg

What more appropriate place to start than a house—the edifice of family history, values and behaviors that can’t help but harbor conflict as each individual grows and succumbs to or challenges the dynamics both within the walls and in the world outside? At an overtly tragic moment in the life of two sisters, their father, Gustav Borg (Stellan Skarsgård), makes an appearance after many years of separation. Though his daughter Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas) has sent him an announcement of her mother’s death, he takes Agnes and her older sister Nora (Renate Reinsve) by surprise when he shows up at their memorial gathering. Lost in thought as he lumbers out of a hired car, donning a black overcoat that sags over his shoulders and outstretches his aging body, he puts on the old charm once inside. Before leaving, he’s awkward but adamant as he insists on a “proper talk” with Nora, an actress, while he’s still in town.

Soon thereafter, across a café table, Gustav pushes a screenplay that he’ll direct. It’s about a young mother. “I wrote it for you,” he tells Nora. “You’re the only one who can play it.” He plans to shoot the film in the family home. She’s outraged. He abandoned them to pursue his own life. Even as a director, but more important, as her father, he hasn’t attended her theatre performances or ever acknowledged her career. He himself hasn’t made a film in 15 years and can’t control his drinking. She’ll have no part in his project. To make matters worse, circumstances soon allow him to cast an American movie star, Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning), in the part meant for his daughter.

In an absurdly comic scene, Nora and Agnes observe Gustav showing Rachel the room where his (real) mother died by suicide. To better understand her role, Rachel asks for more back-story about her, but Gustav tells the actress, “This is not about my mother.” In fact, as we shall see, it somehow is, but he wrote the role for Nora, even if part of him knows it’s about himself, a self he sees in his daughter, a self that needs to be discovered and understood.

The differences between the overly zealous Gustav and the anxiety-ridden Nora—weaknesses they do everything to hide from each other—dissipate like smoke in the wind, almost without our realizing it, the closer we get to each character. The two personae are hardly flip sides of the same coin, but more like the same face on it, their inherent gifts and learned choices so deeply connected, even when appearing only superficially parallel. Irony quickly dissolves into paradox.

If he’s a congenial cad, she’s a self-effacing flirt, and neither shies away from inappropriate ways with Agnes’ young son Eric. Nora challenges him in spitting contests and teaches him how to listen-in on adult conversations through the old stove pipe, while Gustav bestows upon him racy adult VHS tapes and teaches him “violent” shooting techniques with a camera. Even as sparring partners, both father and daughter display an inner respect for Agnes as “the rock” of the family though she’s the youngest. More significantly, both Gustav and Nora have been crushed by parental loss and then sought their only outlet in the arts. Nonetheless, Gustav’s drinking exacerbates his heart attacks and problematizes his career, and Nora’s stage fright ultimately rears itself as a phobic disorder leading her to call in sick and cancel work.

And this is all for two other characters, Agnes and Rachel, to figure out, much as we rely on them for our handle on reading the push-pull tug of war between Nora and Gustav. Rachel and Agnes play crucial roles that get to the core of it. While we watch first Nora and then Gustav each tackle their private battles with the arts (theatre and cinema, respectively), we see that their fight is really not against each other, but with a shared legacy, symbolized by the century-old “gingerbread” house of their past. The younger sister and the American actress both discover Gustav’s and Nora’s common cord, an internalized emotional burden, through research, Agnes in retrieving archival documents and Rachel in rehearsing her acting role. Hence, they become agents of change—not in the ruthless interventionist models of modern psychology, but in the mode of quiet compassion coupled with patient attention, keen observation, and honest communication. Each one extends beyond what her role calls for (whether as younger sister or movie actress) and pleas for a new direction.

Visions and Voices

I found, through a piece of paper, a witness to the accounts of my grandfather’s imprisonment. It’s provable. No one can deny that a terrible thing happened to him. With where the world is right now, that’s a very important thing to remember: that we need to learn from history. My film asks this question of the ambivalence of history and memory. On one level, we need to forget, to forgive a difficult parent. On the other hand, we owe it to the past to remember certain things, not to repeat those faults. And we owe it to the people who experienced certain things. That’s the space where we live in time, in between those two notions.

Writer-Director Joachim Trier

Trier’s seemingly straight-forward family drama, as air-tight as it is with its nest of characters in one historical home, allows many points of entry. The film is as light as its jaunty score and as dark as its past; it’s also as deep and complex as it is lyrical. Trier himself has called it “polyphonic” in reference not only to its characters but also to its time periods.

If we look at lyricism as a longing, a wish and a hope for a special chance, a leap of the heart for a new day, then the film’s lyrical point of view belongs to Gustav, the woe-begotten antagonist who washes up against the storied house like a smelly red tide amidst his ex-wife’s memorial gathering. The ‘70s jazz-folk score and other musical tracks come from his era, and ironically he, the intruder who comes “crawling out of the woodwork,” so to speak, is the rainmaker who’d like to set things right again. Clearly the dramatic point of view belongs to the house itself, as delivered in the child’s voice of Nora reading her 6th-grade essay and as figured in a crack in the wall that was never mended. Yet a “stage-door” entry into this family through theatre and acting opens to her adult character point of view, a “bleeding” of Nora with her performances.

There is also a historical point of view, socio-political and familial-psychological as it is, and that belongs to Nora’s younger sister Agnes, a professional archival researcher. And then, haunting the house and the family is a narrative point of view in the voice-over by Bente Børsum, the real-life actress in films by Trier’s own maternal grandfather, Erik Løchen, a jazz composer captured in Norway’s Resistance and sent to Nazi work camps before he became a renowned filmmaker. Børsum’s mother, Lise Børsum, also a Resistance fighter, spent time in Ravensbrück concentration camp. When she returned, she abandoned her husband and child. The voice of Bente Børsum evokes these stories and casts them as shadow figures who cannot be ignored in the household.

All of these viewpoints inhabit the home where Gustav and his daughters grew up, a kind of ghost house worthy of Ibsen or Bergman. A fifth party—the “movie star” Rachel Kemp—stumbles along trying to penetrate it from the outside; it’s not possible, at least not at first.

The film is polyphonic even within a given character. Take Gustav: there are voices he shuts out (those of his two daughters) and that he blocks (his deceased mother’s) and that he lets in (Rachel’s). They play out on separate levels—conscious disavowal with his daughters, tormented oblivion with his mother, willful trust with Rachel. Trier has time and again invited viewers to ponder the multi-faceted nature of the man and the artist:

It’s interesting for the audience to consider whether Gustav’s primary urge is reconciliation. Does he want to do something with his daughter? Or is it primarily just wanting to make a film? Or is it mainly to resolve his relationship with his mother and the trauma around her death? Or is it everything, and he’s confused, and he doesn’t know, and he doesn’t quite have to know, because at the end of the day, he knows how to craft a movie, and that’s what he does? All of those things could be playing out at different levels of his psyche at the same time or at different times.

The House that Joachim Built

In Sentimental Value, Trier navigates the texture of Gustav’s temperament with finesse, adroitly cutting to intermittent black screens to bring us the layers of his psyche and emotional needs. The black frames remind us, almost unconsciously, that we’re watching a film, that we’re outside looking in, and they jump-start our thoughts and feelings in a given moment. Yet there is a fundamentally “meta” quality to numerous key scenes that quietly allows the whole film to shimmer with a self-reflexive sheen. The most obvious is the opening scene with Nora backstage, highly dramatic but only an indicator of what’s to come. There are also more “tour de force” scenes such as the shift to another era, another film entirely, unannounced until we are pulled out of it to the dark theater where we observe first Gustav and then Rachel crying, as was Agnes, herself the child actress on our screen-within-a-screen that delivers one of Gustav’s first films with a “one-er,” as Rachel would come to note—a long sequence that evolves from an exterior wide shot of fields and a chase, panning to an interior close-up as the girl boards a train, slowly moving in to show her terrified eyes fill with tears—all in one shot, presumably with a hand-held camera.

It’s magnificent footage, one of many splendid scenes in which the lighting and the composition of images feels magical. For instance, it’s followed soon by a dreamy sequence of Gustav on the beach after his Deauville retrospective. He ambles alone at twilight, lost in reverie as an organ chimes from a distant time. A single rider drives a one-horse cart along the waves with charcoal, plum, and mauve clouds floating above the horizon, turning from silver to platinum. As in a fairy tale, an emissary whisks him away to the exclusive table of Rachel Kemp, where he dines with the flattery of three women. Back at the beach thereafter, lovely with laughter from Rachel in her gold lamé dress, it’s champagne until dawn, the clan dozing beneath a rainbow of umbrellas until the horse-drawn cart returns and Gustav hails it, raising a bottle in the air to halt the “carriage” that will deliver the princess back to her palace. Alone again, his heart strikes back, and Gustav downs his medication with the last of his liquor.

Two subsequent scenes, both interviews of a sort, also highlight the respective arts at play. In a punchy satire when a “Tic Toc troll” (as Gustav calls him) taunts Rachel with her recent box-office flop and Gustav with a shaky Netflix come-back, we get a laugh with the auteur’s nasty send-off of the snarky journalist.

There’s a more pensive irony—a more interior luminosity—in a mini-two-hander between the actress and her alter-ego, set not on the stage but in the audience section of the National Theater where Nora performs. A wide shot of Rachel’s interview with Nora transpires in this alternative empty “house,” where the rounded backs of hundreds of red-upholstered seats fill the frame like a sea of petals where two roses face the vast depths of the psyche. Gustav has asked Rachel to dye her hair auburn (and even to attempt a Norwegian accent) in the hope of resurrecting his daughter in the role embodied by the American actress. Countering the Hollywood stereotype of the “dumb blonde,” Rachel sincerely searches for the deeper cord that could connect her to the role, or more importantly, to Nora; for in her uncanny resemblance to Nora, Rachel probably intuits that she is really the doppelgänger of Gustav. It’s this aging, drinking, lost father who sees himself in Nora, who sees his impending death—and hers. Can he prevent both? Maybe at least one, and art is the lifeline.

If his unforgettable creation of Agnes as “Anna” was the first manifestation of Gustav’s survivor guilt, revealed in his earlier film, he knows how deeply Nora could be the second. He is even cagy enough to enlist his grandson to play himself as a seven-year-old when his mother died; the psychodrama is Gustav’s—and Nora’s. It’s the connection, the shared experience, the feeling—the sentimental value—that matters, and this father’s film is his way of showing it.

Sentimental Value

Producers: Maria Ekerhovd, Andrea Berentsen Ottmar; Director: Joachim Trier; Screenplay: Joachim Trier, Eskil Vogt; Cinematography: Kasper Tuxen Anderson; Editor: Olivier Bugge Coutté; Composer: Hania Rani; Production Design: Jørgen Stangebye Larsen; Sound Design: Gisle Tveito, MPSE; Costumes: Ellen Dæhli Ystehede.

Cast: Renate Reinsve, Stellan Skarsgård, Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas, Elle Fanning, Anders Danielsen Lie, Jesper Christensen, Lena Endre, Cory Michael Smith, Catherine Cohen, Andreas Stoltenberg Granerud, Øyvind Hesjedal Loven, Lars Väringer, Marianne Vassbotn Klasson, Vilde Søyland.

133 min., 35mm, Color. In Norwegian and English with English subtitles.