3-23-15

Prints and Impressions: Esther Yune, Piano

By Diane Sippl

Preview, Pasadena Conservatory of Music, March 19, 2015

Solo recital, Mansions and Music series, March 22, 2015

Estampes (Prints), Debussy

I. “Pagodes” (“Pagodas”)

II. “La soirée dans Grenade” (“Night in Granada”)

III. “Jardins sous la pluie” (Gardens in the Rain)

Feux d’artifice (Fireworks), Debussy

Jeux d’eau (Fountains or Water Games), Ravel

La valse (The Waltz), Ravel

This piece (was) inspired by the noise of water and by the musical sounds that let one hear its spray, cascades, brooks…without… subjecting itself to the classical tonal plan.

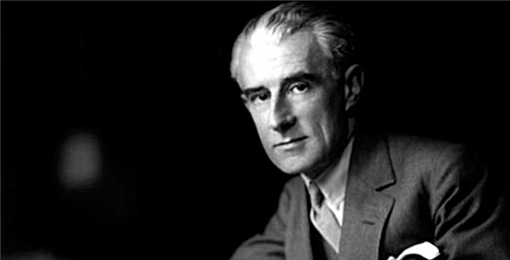

Maurice Ravel re: Jeux d’eau

Music is the silence between the notes…

Claude Debussy

…I give more air to the sound. I like to leave something empty, some space in the bottle, so that we can pour our imaginations into it.

Esther Yune, pianist

Slender fingers walk like spider legs over the keys with gentle finesse yet a reserve of power. They flow like the tentacles of a hydra, rolling and spreading from her undulating wrist even for the most percussive, staccato notes. Such is the precision and eloquence of Esther Yune in her solo recital of “Prints and Impressions,” and such is the privilege of sitting nearly within arm’s reach of her and the piano during both the preview at Pasadena Conservatory of Music and the performance at the 1930 Mediterranean villa of Betty Sargent and John Swain in the latest installment of Mansions and Music held thrice annually.

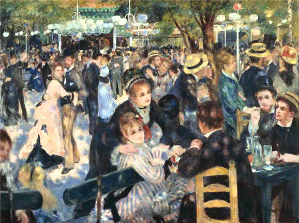

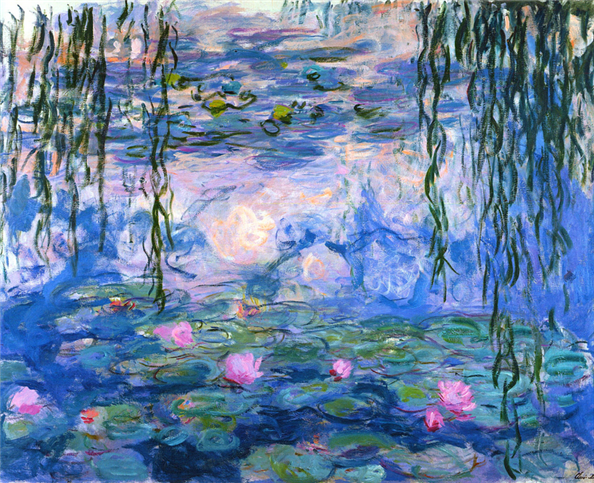

Water and air, color and light — if these were the basic elements of Impressionism in painting, what could the sonic dimension possibly add? One answer is movement: the lively interplay that visual artists created in the spaces between oppositional pigments, between light and shadow, between dreaming of what had passed and longing for what could be. Music could paint these pictures by moving in time, in dynamic tempos and tones — through melodies and harmonies fleeting or elongated, resounding and overlapping, or suspended, deferred. Like Monet’s floating lilies and rippling waves, Degas’ bending ballerinas and racing jockeys, Debussy’s Estampes and Feux d’artifice as well as Ravel’s Jeux d’eau and surely La Valse enacted explosions of perception in the most unforgettable and indelible tensions of experiment and resolution.

The painters’ Impressionism was, after all, a loss of substance, the dissolution of space, into vibrating colors. It developed as an art of indistinct forms dissolved by broken brushwork to approximate the visual perception of temporal and atmospheric sensations. To paint the transitory effects of shifting light and movement, the artists “orchestrated” the entrapments and reflections of color they encountered in their plein-air painting. One historian has called their collective output “a skilled choreography of color, pattern, and brushwork as a record of the kinetic process of artistic creation.”

“Music is the silence between the notes…” remarked Claude Debussy, considered the first proponent of musical Impressionism. Like the spaces between the broken brush strokes or the juxtaposed color complements on the canvas, that silence elicited movement through time. In What to Listen for in Music, Aaron Copland noted that Debussy was a composer of neither the traditionalist type (such as Bach, who surpassed others in mastering the musical style of his day) nor the constructive type (such as Beethoven, who each time began with one musical theme) nor even the spontaneously inspired type (such as Schubert, whose compositions arrived in his imagination as wholly formed entities) — but of the pioneering type who, opposing conventional solutions, experimented to find new harmonies, sonorities, and formal principles.

It was elusive and fragmentary material that gave rise to Debussy’s melodies. He swept aside existing theories of harmony and was accused of excessive dissonance, even if this was only a simple matter of chords played fortissimo or pianissimo on one instrument or another. He saw in the piano unique possibilities for the melding or distinction of notes, from velvety vibrato to brittle brilliance, depending on the use of its pedals. With a near paucity of models, Debussy delivered free forms of music that inspired and influenced composition and performance for a century to come. Feux d’artifice (1912-1913) is but one of twenty-four preludes for piano (the last), each distinctly innovative in form. Colors, images, and technical demands abound, while their titles, which Debussy inscribed only at the end of each piece, ensured the performer’s freedom of imagination.

Debussy relied upon his intuitive ear to produce aural sensations that reflected images from his life experience. In Estampes (1903) he evoked a Javanese gamelan for “Pagodes,” where overtones dissolve into each other with the musician’s use of long sustaining pedals. He moved from a traditional Asian melodic style for “Pagodes” to the vivid colors of habanera rhythms for “La soirée dans Grenade” and impressed Manuel de Falla that he could evoke Spain without ever having been there or borrowing from its folklore.

He did draw from French folk songs for “Jardins sous la pluie” but changed their rhythm in creating new images and harmonies for wind, raindrops, and thunder.

Ravel’s inspiration was often not only auditory but tactile. In 1901 he wrote on the manuscript of Jeux d’eau, “River-god laughing as the water tickles him.” The piece was based “on two motives in the manner of the movement of a sonata,” but within that well-conceived form he structured his own tonal language, employing lyrical melodies and evocative harmonies with strident effect, sometimes irony and a heady dissonance.

Written in 1919 and 1920, La Valse was conceived as a ballet. “We are dancing on the edge of a volcano,” Ravel wrote in his notes to the composition, quoting the Comte de Salvandy. What he referred to as a “choreographic poem for orchestra” he then transcribed for two pianos and also for solo piano, commanding technical virtuosity of the pianist.

George Benjamin referred to the composition as a “one movement design” that “plots the birth, decay, and destruction of a musical genre: the waltz.” Stephen Johnson characterizes it as two giant waves, one reaching the height of ecstasy and extravagance — of the popular dance, of Vienna, of the Austrian Empire — and the other, foreboding, resounding but not repeating the first, reaching its macabre doom.

Ravel was drawn to both the beauty and the disintegration of the waltz form, and envisioned La Valse set in the Imperial Court of Vienna in 1855 (its original title in 1906 was “Wien”). He called La Valse “a sort of apotheosis of the Viennese waltz…the mad whirl of some fantastic and fateful carousel.” Yet he refused to relate it to the devastation of the Great War, or his experience there where his friends were killed and he fell ill upon his return, or the death of his mother a bit earlier, or any particular event or trauma, stating, “While some discover an attempt at parody, indeed caricature, others categorically see a tragic allusion in it — the end of the Second Empire, the situation in Vienna after the war… this dance may seem tragic, like any other emotion…pushed to the extreme. But one should see in it only what the music expresses: an ascending progression of sonority, to which the stage comes along to add light and movement.”

Ravel found the rhythm of the waltz compelling and wanted to pay homage to its form and to Strauss and Chabrier. Yet his preface to the score states the very tenets of Impressionism: “Through whirling clouds can be glimpsed now and again waltzing couples. The mist gradually disperses, and at letter A a huge ballroom filled with a great crowd of whirling dances is revealed. The stage grows gradually lighter. At the fortissimo at letter B, the lights in the chandeliers burst forth. The scene is an imperial palace about 1855.”

When Diaghilev, who had commissioned La Valse from Ravel so that he could produce it on the stage, heard him play it with Alfredo Casella, the impresario commented, “It is not a ballet, but a portrait of a ballet, a painting of a ballet,” and he rejected it, eliciting a deep animosity between the two that years later led Diaghilev to challenge Ravel to a duel (albeit one that never came to pass).

Post-preview on March 19th, I spoke with Esther Yune and at once took a look at her hands close-up. She stretched them out in front of me. “They’re really small,” she showed me. “I tell my students, ‘Look, if I can reach the keys, surely you can…’”

The enthusiasm in her voice and her eagerness to share (she is, after all, not only a performer and mentor but also a professor of music history and analysis and an active adjudicator for competitions) sparked a number of questions from me:

KINOCaviar Why did you choose these two composers, and these particular compositions, for your performance?

Esther Yune In my opinion, the number of stations and channels for listening to classical music today is becoming less. When I want to reach the general, everyday public with a performance, I look for pieces that allow for extra musical images, because the audience can relate to these better. In planning my programs, I go for some kind of story or some type of contrast. I chose Fireworks (Debussy’s Feux d’artifice) and Water Play (Ravel’s Jeux d’eau) because they are contrasting within the same program.

KC How do you interpret these pieces differently from the ways that other pianists do?

EY I add notes; not all that I play are written. In performing La Valse, you have to add notes, and what you choose to add is up to you. Ravel himself has different versions, so if you play just what’s written, it’s very dry, and it doesn’t offer all these images. Some performers still play it that way, of course, but it’s not very interesting. Everyone’s interpretation of La Valse is a bit different from those of others. I add some chords each time I play it, try for rich images, maybe cut back slightly; I change it a bit each time. Ravel calls for improvisation.

KC Is there such a thing as an “impressionistic” performance style? How so?

EY That’s a good question. Impressionistic paintings are meant to be seen from far away. It’s the same with the music. When you open the composer’s notation, you see there are many notes, but no one note is important. The artist should think of the overall images and colors.

KC This music requires a virtuosic performance with its dense textures, glissandos, and bountiful scalar and arpeggiated figures. I noticed you often playing with one hand crossed over the other for these pieces.

EY Impressionistic music runs all over the keyboard. One hand establishes the pattern, the atmosphere; the other is for pointing out different notes. The cross-hand technique is for expression.

KC What challenges do Debussy and Ravel pose for technique?

EY Ravel is the hardest: if you focus too much on technique, you lose the music. There are people who play it perfectly, note by note, with perfect technical mastery. For me, impressionistic music isn’t just technique, but color.

I studied with Barry Snyder at Eastman, who is known for colorful tones. He taught me that you don’t press down on the keys with so much energy. Of course in some places, you play with full force, but in general I give more air to the sound. I like to leave something empty, some space in the bottle, so that we can pour our imaginations into it.

Esther Yune, PhD, faculty, PCM, 2004-2008

Pasadena Conservatory of Music

100 N. Hill Ave, Pasadena, CA 91106

pasadenaconservatory.org Tel. 626.683.3355