3-11-11

Catherine Deneuve, No Potiche, Reigning Supreme in Ozon’s Latest Opus

By Diane Sippl

Amidst a mini-retrospective, “Beautiful Dreamer: The Early Films of Catherine Deneuve,” running from March 4-12 at the Bing Theater, the world-renowned actress paid a precious visit to avid fans at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on March 8, 2011, following a preview of her new film, Potiche by François Ozon. The series also features Luis Buñuel’s Belle de Jour (1967), Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965), Jacques Demy’s Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and Donkey Skin (1970), and François Truffaut’s The Last Metro (1980). In a relaxed and convivial conversation, this guest célèbre responded to the eager curiosity of host and programmer Ian Birnie.

Potiche takes us to a quaint town in the French provinces in 1977 where Suzanne Pujol, a pretty, haut-bourgeois wife who knows her place, is recruited to step into her husband’s shoes when this irascible tyrant, the boss of the umbrella factory she inherited from her father, has a minor heart attack upon being taken hostage by his workers who are on strike. Suzanne stuns everyone with the friendly role she plays, negotiating the needs of workers she’s known since childhood and even doing her own kind of “collective bargaining” with the aid of the Communist mayor, who turns out to be only one of her many old flames. In time, even he must come to reckon with a new Suzanne whose motherly kindness and competence take her beyond the home and the factory alike.

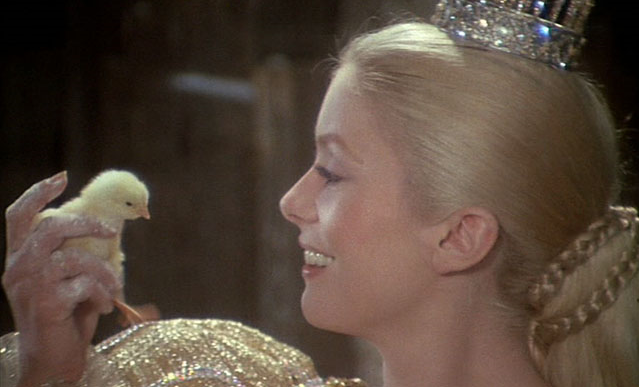

Donkey Skin by Jacques Demy

It’s tempting to see Potiche as a compendium of riffs on

Catherine Deneuve’s earlier roles, especially in the middle of LACMA’s

captivating series. Her springtime jog

in nature that opens Potiche spins on

her élan at the outdoor organ in Donkey

Skin’s rustic setting, just as her kitchen song and dance in Potiche recall Donkey Skin’s cake d’amour

scene. A parapluie factory (call it

Piganiol à Aurillac) drenches the film in the colors and ambiance of Umbrellas of Cherbourg. A lost locket with facing cameos of Deneuve

and Depardieu in Potiche could be a

keepsake from The Last Metro and

comes to life as a romp in the woods (a pastel, lady-like echo of Belle de Jour’s dream with the “potiche” in pink floral chiffon); this flashback in Potiche re-enacts Metro’s moment on a theater floor as if Depardieu, over time, had

simply snowballed into the labor-leader mayor he is in Potiche.

Gone are all the psychological menaces, perversely logical desires, Freudian fairy tales, repressed fantasies, obsessions and schemes, but not the sadder-but-wiser heroine, who emerges as even more worldly, knowing, and sympathetic than in earlier films. Beside Séverine’s uncanny acuity in Belle de Jour, Suzanne’s awareness is informed and palpable. Evoking personages of contemporary renown from Madame Chirac to Ségolène Royal, Ozon’s Potiche poses Deneuve in the limelight that Truffaut first cast on her in The Last Metro, in which her unconscious authority comes full bloom beside a dependent husband-playwright hidden in the cellar who would like to pull the strings on the “action” from afar. Metro sets the stage for Potiche, in which the ousted executive presumes to run a factory from his sickbed or his vacation in Italy, teetering on becoming a potiche himself.

Potiche by

François Ozon

Adroit at his craft as director, and here executing his most masterly precision of technique in timing, rhythm, and tone, François Ozon has also shown himself to be a keen writer with such gems as Under the Sand and The Swimming Pool. Now he has tweaked the original hit play by Pierre Barillet and Jean-Pierre Grédy by adding his own updated ending, improvisations with the actors, pop culture inflections, and flourishes of style — all with phenomenal verve, incisive wit, and deep resonance. Potiche is punchy like the best of screwball comedies. It runs along at a clip with Suzanne, in her tracksuit and curlers with a poet’s jotting pad in-pocket. Squirrels play and rabbits hump each other, and the radio songs send Suzanne reeling. This boulevard farce bubbles over like champagne at a matinee, yet Ozon lets the giddy laughter subside long enough for us to cringe with Suzanne’s humiliations. Before we know it, he’s left us with a seriously thoughtful feminist success story interpreted by an actress who can call herself both a proponent and a product of the women’s movement. (Deneuve was among those who signed the Manifesto of the 323 Bitches for abortion rights in the 1970s.)

Ozon’s take on the play Potiche is worth noting both as a pointed satire on today’s sexual hiearchies and as a salute to Catherine Deneuve. “In France, theater de boulevard is a genre characterized by light, silly, often outrageous comedy,” he explains in his production notes. “Typically, all possible transgressions are explored — social, familial, emotional, political — but in the end, everyone always lands on their feet. Middle-class audiences want to laugh at all that is titillating or frightening, as long as everything goes back to normal in the end. In my adaptation, I tried to shake things up for real; as a woman, Suzanne finds a legitimate place in society, turning the patriarchal order on its head….”

François Ozon directing Catherine Deneuve in Potiche

Having worked with Deneuve previously in 8 Women, Ozon felt comfortable casting against type when he asked her to play the lead in Potiche. He wanted her to be able to evolve in his film not only on the level of the story line but in all layers of the production: “In the beginning, Suzanne is a caricature, as are the other characters. She’s the good little wife of a small-town factory owner, but gradually, she breaks free and undergoes a series of transformations to become a new woman. Using the character as a starting point, I wanted to explore the woman, and then end the film with the actress, in the final scene.” It’s a finale in which the actress, singing, gives new life to an old song, “C’est beau la vie.” As Deneuve herself has pointed out, Ozon is a “great deconstructionist.” Potiche, all-in-all, is a meta-discourse on the many roles a woman can play, in every sense of the word, as an “actor” — on the stage and the screen, in a home and a community, in a society and a culture.

In a basic black sweater and skirt, Catherine Deneuve, sitting on the stage of the Bing Theater, may have tempted audience members to project upon her any of her roles in her previous one hundred films that they cared to conjure as they gazed at her familiar cover-girl image, but her actual responses to each question in the conversation were as idiosyncratic and sparkling as the gossamer-weight bracelet that graced her slender ankle.

Judith Godrèche, Catherine Deneuve, Fabrice Luchini, Karin Viard, Jérémie Renier, and Gérard Depardieu in Potiche

Ian Birnie What can you tell us about your experience acting in Potiche?

Catherine Deneuve Well the director, François Ozon, was also behind the camera, so he was very energetic. Also we had to complete shooting within eight weeks, which is not very much for a film like that, and he was very well prepared, so there was enough time, even though there were a lot of people involved in this film, so it went well. It was really nice.

IB And you’d made Eight Women with him. So that must have given you a level of comfort — with his experience, his style.

CD Yes, I’d worked with him, and I think I’d seen almost all his films, so I knew him as a director, the way he likes to do things, to take some normal situation and change it in some bizarre way. And that’s something I like, especially for a comedy.

IB Did you feel related to the character?

CD Well I like the character very much. I don’t know what potiche means for you, because the word has been translated as ‘trophy wife’, but it’s not that, exactly, because for us a potiche can also be a man. It’s a beautiful object that is very decorative that you put somewhere and it does not have much use except to look good and be there.

IB We call it a ‘knick-knack,’ or a ‘dustcatcher’. You just dust it.

CD You know, anyone can be a potiche, for a few hours of a day, or in a lifetime; everybody has been once in a situation of having just to be there, to be with someone and have not much to do or to say to other people who are there. For a few hours, you can be a potiche. I’m sure everybody knows that situation at least once.

Judith Godrèche, Jérémie Renier, Catherine Deneuve, and Karin Viard in Potiche

IB Did you enjoy wearing the clothes?

CD Well that was really the start, the beginning of the preparation of the film and of the character. You know when you have to do all those scenes in those very strange and beautiful clothes and to try the hairstyle, all that counts a lot for building the character.

IB And you were involved very early on in the project.

CD Yes, because Francois talked to me about the film. The script was not completely developed; it was not written yet. The play was there, of course, but he had not started to write the script. He told me the story, and I said ‘yes’ before the script was finished, because it was a very, very good story and an interesting part.

IB And it’s a big part. I mean, to play the lead for that kind of character is not that easy.

CD Not that easy, no. And it’s not easy, either, to work with him every day, doing all the shots, all the scenes. I was afraid, so I did prepare myself to be in good shape to follow him.

IB Your career is remarkable, and in the last years you seem to have worked with a lot of young directors —

CD More and more the directors are younger than me, that’s for sure!

IB But you take supporting roles, which have really interesting characters, such as in A Christmas Tale. That’s a fascinating character.

CD Well I think it’s important to choose also for the story, for the director, and for the interest you have in the film itself, not only the part.

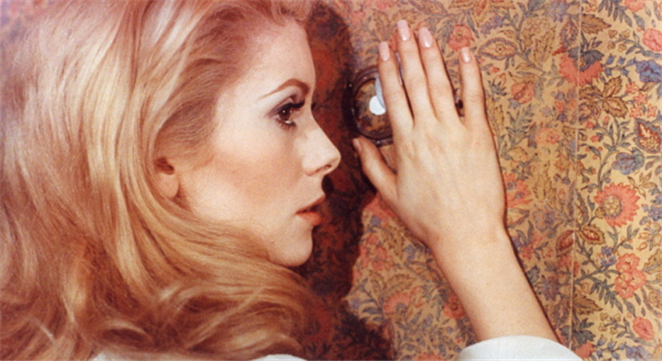

Belle de Jour by Luis Buñuel

IB Can I ask you about some of your early films as well? On Friday we screened Belle de Jour and Repulsion, and Repulsion has, like most of them, an exhausting role.

CD It’s a powerful film, and I know there are lots of copies in stores and in the theaters they show it more. I think the film sort of aged quite well, mostly because it’s in black and white, and I don’t think that helps a lot, but the subject is very dark, and it was a very tough director.

IB That must have been a hard film to make — both of those films must have been hard. They’re intense, and you’re an object of scrutiny.

CD Yes, and I remember sometimes in scenes where you have those special effects in Repulsion, where Carole starts to see differently, it was more fun than you think… This was very important. It’s very basic, but Roman did special effects. There’s not anyone who would do it that way now.

IB Do you stay in touch with people you’ve worked with?

CD Oh, some of them. It depends on who I meet. With Roman, yes, he’s someone I stay in touch with..

IB And what do you look back on over the years? Are there certain highlights, like working with Truffaut on The Last Metro?

CD Frankly, I don’t look back that much. Sometimes, yes, because I have to present a film or a retrospective, or someone comes to talk to me about Buñuel or just Tristana, so I answer and I go back to that situation at that time; but after that, since I’m still working a lot and doing things, I don’t have nostalgia, though I’m very pleased to have done these films and to have been involved in these projects.

Gérard Depardieu and Catherine Deneuve in The Last Metro by François Truffaut

IB You work a lot. Is it because you need to, from an emotional point of view, to do the acting? I know you’re a film buff.

CD I see quite a lot of films, so it’s part of my life. I suppose I would stop if I didn’t have the excuse that for me it would be interesting in the end, because it would be really not worth it for me to make a film. But for the moment I’m very lucky because I’m involved with interesting directors.

IB Have you done stage work as well?

CD No, never. Only in films — I mean like Metro.

IB No Broadway? “A Little Night Music”?

CD I like music very much. I love to sing.

IB Would you like to work in the US again? You did two films, back in the early ‘70s, late ‘60s. It was a different Hollywood.

CD Well, Dancer in the Dark was a project that Lars Von Trier really wanted to do, and he wrote to Björk and she wasn’t too keen about being in the film. I don’t know if she was interested much in being an actress. She’s such an incredible personality, but she has to be really in charge of everything she does. So she realized, maybe, that she would have to be directed, and she was not ready for that; it was really difficult. If she had not done the part, I think the film would not have been made. So she finally did it, but it was difficult sometimes.

IB When you work with other actors and co-stars, is your relationship important? I’m thinking of with Depardieu. It seems so natural in this film.

CD Well, yes, I’ve done several films with him, and it’s quite different. Not only is he a great actor, but he’s a very, very nice partner. He loves acting. He’s uplifting. You feel safe and protected with him.

Judith Godrèche and Catherine Deneuve in Potiche

IB What was it like working with your daughter, Chiara Mastroianni?

CD I just finished a film with her.

IB Oh, you did. I know there’s A Christmas Tale.

CD Yes, but in A Christmas Tale she’s my step-daughter and I don’t have a scene with her. But I just finished a film of Christophe Honoré called Les bien-aimés, The Beloved, where I’m playing her mother, and there are a lot of songs in the film, a lot.

IB He likes to do a kind of new musical.

CD It’s not a musical, but there are about forty-five minutes of songs in the film.

IB Did you encourage your daughter to become an actress?

CD Oh, no. She doesn’t ask me anything, anyway. She decided. But if she had asked me, I think I would not have encouraged her, because it’s so difficult to be an actress. I mean to work. Not to be an actress, but to be an actress working.

IB Well, and to be a celebrity.

CD I didn’t have much of a public life. I was very protective of my life at home. And also, in Europe, I think it’s different.

The Last Metro by

François Truffaut

IB I know you came from a theatrical family.

CD Well they were stage actors, my parents, you know. But we were quite a family, so the life at home was like normal life at home, with my mother working, though she had four girls. We were raised very normally. My parents had something very important for me — they had fantasy — but we had a normal life, also.

IB For young actresses coming up today, how do you encourage them?

CD I don’t encourage them. I’m not very positive for that. But if someone comes and asks me, I say, ‘Are you ready to live this life?’ You have to be quite strong, today, especially, to be an actor or an actress because it means that you are not going to do very important work for quite a long time. I don’t know about in America, because I suppose here you can do another job, if you’re young and you want to be an actor. Very often I’ve read that actors are waiters or waitresses in restaurants, but we don’t have that in Europe. It doesn’t work like that.

IB No? All the waitresses don’t want to be actresses?

CD No, but we have a system that helps people who don’t work too much to survive.

IB Is it a good scene — is the atmosphere there good for actors today?

CD Well the French scene is good. Cinema is doing quite well in France. At the moment, it’s good figures, better than before, and French films have been doing quite well in France, yes, quite well.

IB And I think there really is finally a European consciousness as well.

CD I don’t know if that’s true, but I know that in France the situation is not that bad.

IB There are still subsidies.

CD Yes, which is normal for a civilized country! I think that art should be subsidized. Art, music…. It’s not a right, but it’s something that should exist in a country.

Repulsion by

Roman Polanski

IB What’s coming up?

CD Well, I have a new film coming out in two weeks’ time in France, by a young director, Thierry Klifa, called His Mother’s Eyes, and then I’m going to have another release.

IB The Big Picture?

CD I don’t know if The Big Picture is going to be released in the States. It was shown in New York, and it might come out. I have a very small part, and it’s very interesting.

IB Coming full circle to Potiche, what has changed for women since your early films, from Repulsion to The Last Metro?

CD I don’t think women were more potiche thirty years ago. The difference is that women are working more than they used to, not just actresses. Women are working more, so the image of women has changed in thirty years, a lot. And working with Roman was probably one of the most important experiences I had — with Truffaut and Polanski, these are great directors. Not “director” in the sense — well he doesn’t work so much with actors — but the stories he wants to tell and show you are really incredible.

IB Do you enjoy working with women directors?

CD Well, it depends, because you see, that’s very much the same. A director has to be a good director. I’ve worked with some women who were very fussy, and I was like I could have been with a man director; and then also I’ve had very nice experiences with woman directors. I don’t like such a difference between a man and a woman as a director because they have to be good.

IB I liked very much your performance in Place Vendôme. That’s a woman director and a very interesting character.

CD She’s a very good actress, too, Nicole Garcia.

IB Catherine plays an upper-class woman, a diamond dealer, who’s also basically falling apart as an alcoholic, and it’s amazing.

CD It’s a very good script. You know, it’s very difficult for a French film, if you don’t have a distributor who really believes in the film and gets it released. A film must have a public.

Umbrellas of Cherbourg by Jacques Demy

IB Are there any directors you would like to work with that you haven’t, or who you think are good directors?

CD There are a lot of good directors. I’ve done a lot of films in all these years, but still there are directors I haven’t worked with and would never work with. Directors who I admire for their films are Coppola, David Fincher, Wes Anderson. There are a lot of directors.

IB Well, we’ll let them know.

CD No, no. People always ask, ‘Who would you like to work with?’ About three-quarters of the directors of the world — South Korean directors, Chinese directors.

IB I wish you had made a film with Chabrol.

CD Why?

IB You were working with other directors from the nouvelle vague…

CD Yes, but actually the only time I worked with him was a long time ago because he wanted a pregnant woman in a film he was doing, a sketch. He wanted absolutely to have the wife of the man in the film be pregnant. And Stéphane Audran was pregnant the same time that I was, and she got a child a little earlier, and he asked me to play the part of Stéphane because I was pregnant at the same time and it was only a few weeks later. So it’s the only time I worked with him — to replace Stéphane Audran because I was pregnant.

IB Well, cinema’s big accident! Thank you very much, Catherine…

Potiche

Director: François Ozon; Producers: Eric and Nicolas Altmayer; Screenplay (freely adapted): François Ozon; Original Play: Pierre Barillet and Jean-Pierre Grédy; Cinematographer: Yorick Le Saux; Editor: Laure Gardette; Sound: Pascal Jasmes; Production Design: Katia Wyszkop; Costumes: Pascaline Chavanne; Original Music: Philippe Rombi.

Cast: Catherine Deneuve, Gérard Depardieu, Fabrice Luchini, Karin Viard, Judith Godrèche, Jérémie Renier, Sergi López, Évelyne Dandry, Bruno Lochet, Elodie Frégé, Gautier About, Jean-Baptiste Shelmerdine, Noam Charlier, Martin de Myttenaere.

Color, 35mm, 103 min. In French with English subtitles.