Perfect Days: Wim Wenders’ Song to Life at the AFI FEST

By Diane Sippl

“Would you be interested in shooting a series of short fictional films in Tokyo dealing with an amazing social project, involving the work of great architects, developing the script yourself, and getting the best possible cast? You would have total artistic freedom.” This is a near translation of a letter that came from Japan to the world-renowned German filmmaker Wim Wenders, who in 1982 had made Tokyo-ga there, tracing the steps of the esteemed Yasujiro Ozu, whom he deemed “a sacred treasure of cinema.” Ever since then, Wenders had been experiencing, as he said, “real attacks of homesickness for the city.”

To us the circumstances might begin to sound peculiar: the ultimate plan was to involve public toilets in “finding a character through whom one could understand the essence of a Japanese welcoming culture.” That’s a lot to unpack. How could toilets play a role in portraying the beauty and civic pride of Tokyo? Place is everything for a cinema poet such as Wenders. Having fallen in love with the Shibuya district some forty years earlier, he traveled there to view the locations and ended up with a Japanese co-writer, Takuma Takasaki, and a leading man, Koji Yakusho.

“Marvels of Architecture, Temples of Sanitation”

Toilets (in Japan) play a whole different role than in our own Western vision of “sanitation.” For us, indeed, toilets are not part of our culture; on the contrary, they are the incarnation of its absence. In Japan, they are small sanctuaries of peace and dignity...

Wim Wenders

The filmmaker visited works by sixteen prize-winning Japanese architects, among them Tadao Ando, Shigeru Ban, and Kengo Kuma, all known for creating huge banks and museums and high-rises but who had recently designed tiny units for The Tokyo Toilet project in the parks of Shibuya. Modern and minimal, each concept and construction differed from the next—some spherical and others cubed, one of futuristic-looking concrete and another of honeycombed wood. One built of glass had translucent panels of lilac, rose, and sunny yellow that turned opaque after someone entered and locked the stall door.

“These toilets were too beautiful to be true, but they weren’t what this film was going to be about,” Wenders later acknowledged in his statement to the press. The film needed a character at the heart of it. “His story alone would matter, and only if his life was worth watching, if he could carry the film, and those places, and all the ideas attached to them, like the acute sense of ‘the common good’ in Japan, the mutual respect for ‘the city’ and ‘each other’ that make public life in Japan so different to our world.”

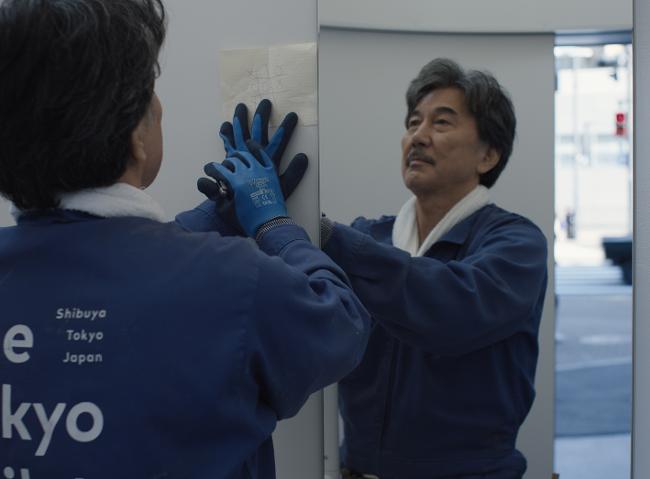

At a point before the film begins, in a backstory we are never told, that character, Hirayama, (named for the family in Ozu’s classic Tokyo Stories), chose to lead a different life, one of “simplicity and modesty” that led him to become a cleaner for the units of The Tokyo Toilet. Dedicating himself to the work as a craftsman to his trade, even building and bringing his own tools with him in his van, each day he climbs into his coveralls, throws a white towel around his neck, a belt of keys around his waist, and exits his humble home turning his eyes to the sky. It’s a new day—yes, each day brings something unique and special.

Was it a famous German architect and interior designer who came to live and work in the U.S. who coined the long-since popular phrase, “Less is more?” When Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, or “Mies” as he came to be known, joined progressive circles in Berlin a century ago, he promoted the idea of casting aside all that does not contribute to beauty or function in architecture and, in fact, in life. Reducing excess and embracing the essential would allow for greater focus, meaning, and fulfillment. What’s maybe more challenging to comprehend is another aphorism Mies embraced: “God is in the details.” Perhaps both tenets find their place in the minimalism of the Tokyo Toilets just as they do in the design and philosophy of Wenders’ entire film.

Stop, Look, Listen!

Nature, music, light and shadow, words on a page—these are all vehicles that bring awe and joy in a lyrical way of life. Let’s fall into the rhythm of the character and discover all that’s indispensable even as it’s ephemeral.

For an hour, Perfect Days might feel like a silent film, but we hear Hirayama snip his moustache, shave his chin, mist his houseplants—his morning routines from room to room colorfully lit in blues and lilacs, golden oranges, sea greens. Breakfast is a can of coffee from the vending machine outside his door where he looks up and smiles as if to greet the dawn, jumps into his van, and pops in a tape cassette, “The House of the Rising Sun” by the Animals. He’s off and running, as he is every workday, from one of Tokyo’s public toilets to another. His late and lazy assistant whines to him, but he just nods for him to get to work. At lunch, he sits on a park bench in the dappled light, photographing a tree with an old 35mm Olympus camera, catching in black and white the shimmering leaves; he gently digs up a sapling, packing it with its soil into a tiny bag, and bows hello to a regular elder who lives there.

We track our tacit protagonist down the multi-layered streets of Tokyo and take his point of view of the city with the sounds of “Pale Blue Eyes” by The Velvet Underground: “Sometimes I feel so happy. Sometimes I feel so sad…” He drives home, gets out of his uniform, hops onto his bicycle and rides to the public bath house. He has a bite to eat in an underground mall, and at home, plops down on his futon again to read a Faulkner paperback, fall asleep, and dream, processing the precious moments spent among the trees in the park.

Another day: the sweeping of the street below with an old-fashioned birch broom awakens him as does the morning light though his windows. This time he plays Otis Redding’s, “Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay” as he drives through the city along Tokyo’s waterfront. His assistant, Takashi, turns up begging to borrow his car and introduces Hirayama to his ever-so-cool crush, who asks to play his Patti Smith tape and “shushes” her rambunctious companion after he introduces her to his senior as someone who never talks.

That night Takashi drags Hirayama to a shop where the clerk is willing to pay $120 for a Lou Reed cassette. Hirayama shakes his head no. “No love for no money!” screams the kid in dismay. Hirayama keeps his tapes and gives Takashi money, in fact twice. Now he can drive home in peace, listening to the lyrics, “Walking through the sleepy city, in the dark…” (from the Rolling Stones) and smiling richly, enjoying the music so much: “No one cares about the city lights. They just care about the warmth inside.” Ironically, it’s Hirayama who has given money for love (for his kooky assistant, in the name of ‘young love’). Driving along the water, he runs out of gas and has no money left to buy some. He takes out the Lou Reed tape again. Walks off. At home, asleep, he dreams again in foggy black and white, and sees a close-up of Aya, his assistant’s crush.

He wakes up to the third day and we catch him after his routine, gazing at the sky and smiling, arriving at his last toilet to clean, and systematically, using his hand mirror to check hidden spots. Then his usual trip to the sentō for a scrub and a soak. "Gokuraku, gokuraku" he says to the regulars in the tub—Divine pleasure, for the body and the soul. That night’s dream fades from dancing leaves to his own dozen tiny potted plants, all basking in close-up in various shades of lilac and framing him as he sleeps, out of focus, in his dark apartment.

It’s a new day, and in the same frame, Hirayama is now in focus as he rises, packs up his mat and pillow, and opens his door once again to smile at the morning sky. It’s repetition each day, but with variation: the camera chooses new placements, angles and distances, and the editing omits different steps and more steps in the daily sequence each time. Today he plays “Blue Fish” sung by Sanchiko Kanenobu, Japan’s first female folk-rock singer-songwriter in the late ‘60s,on his way to work. Sometimes the songs offer premonitions of what’s to come, as this one does, coyly leading up to surprising pleasantries. It seems he may have inspired Aya, a young woman with shared sensibilities, who is a counterpoint to his bumbling co-worker. Oh, what a feeling!

At home, we see his shelves loaded with cassettes topped by a tape player, and he inserts Lou Reed’s “Perfect Day.” He lies down on the floor sans mat, to listen and dream, the shadow play of leaves flickering over his closed eyes. Later he rides to his regular underground mall eatery, greeted with the usual shōchū highball “for your hard work,” and he can’t wipe the smile off his face.

On his day off, when he rides home from a photo lab and we hear the Kinks’ “Sunny Afternoon,” we discover his mountain of books—two cases of shelves, five shelves each, and books stacked all along the shelf tops to the ceiling, andstacks three feet high on the floor beside these! But that’s not all—now we see the whole closet stacked with shallow metal boxes, a filing system for his photos, as he sifts through his developed prints.

Through all these details, Hirayama’s way of savoring each moment slowly seeps into our own point of view, perhaps our world view. Wenders explains,

The beauty of such a regular rhythm, of an ‘always the same’ pattern of days, is that you start seeing all the little things that are not the same and change every time. The fact is that if you indeed learn to entirely live in the HERE AND NOW, there is no more routine, there’s only a never-ending chain of unique events, of unique encounters and unique moments. Hirayama takes us into this realm of bliss and contentment.

Craft

Indeed, the monk-like character we discover at the outset carries out his stoic life in humility and dedication to his daily ritual. Even though we get increasingly abbreviated glimpses of it, as the wheels turn on his van or his bike or his tape cassette players, incrementally deeper feelings accrue through his respect for his work and his sensitivity to other characters. Wenders uses a tender “tinker toy” approach to lure us into Hirayama’s interior being. Like Pajeau, the stone mason who designed these fragile wooden sticks to allow and inspire the imagination in free play, Wenders anchors Hirayama’s movements in spools of song, thereby inviting us to construct the scaffold—to conjure the step-by-careful-step process—by which Hirayama re-builds his life.

Yes, re-builds, because a turning point arrives half-way through the film when Hirayama is moved to speak, guarded as he is. The exchange with a young character dear to him begs a backstory for this man. Wenders has been asked if he himself knows this story (because it’s not shared in the film’s narrative), and he admits that he does but prefers not to disclose it. In discussions, the actor Koji Yakusho lets us know that in preparing for the role, he envisioned a much darker past than the director did. The film’s masonry is open, for us to decide the kind of life Hirayama has experienced prior to our meeting him. We get clues, as we do with the other characters, but in general, the past is elusive, and meant to be so. “Now is now,” Hirayama instructs, and it’s important to fully inhabit the present moment. He imparts this Zen-like message in every breath.

Unexpected Encounters

It’s the conscious awareness of one’s role in a society that drives the character—the tenacity of his struggle, his discipline, his commitment to a new life. We see it already in the opening of Perfect Days when Hirayama hand-carries a stranded little boy from the public toilet structure into the park to find his mother. (The boy was apparently tormented by two other little rascals who ran out of that structure screaming wild as Hirayama walked in for cleaning.) Hirayama empathizes with any “outsider”—whether a lost pre-schooler or a boy who is a silent admirer of his kooky underling at work. As the film sees the world through Hirayama’s eyes, we also see all the people he encounters with the same openness and generosity as he does: for example, a homeless man who is “everyperson,” though Hirayama can see that the man has a different past; his inner life lets the elderly man be at one with nature, and he dances as if he were a tree. Through Hirayama we discover how little this man suffers from being seen as a nobody by most people. (In fact, he is played by the revered and award-winning dancer Min Tanaka). Hirayama’s compassion is also clearly expressed for a dying man he at first perceives as his rival—a bit baffling, but gradually, poignantly felt.

If we are careful to note what does change in Hirayama’s routine, then conditioned by other cinematic narratives, we begin to ask, “Is Perfect Days a love story?” There are, in fact, at least eight women in the film (if we count the anonymous tic-tac-toe player who leaves a mark each time on a paper tucked behind one restroom’s cabinet). There is a quizzically silent girl on the lunchtime park bench, and Hirayama’s co-worker Takashi’s crush, Aya, who shocks Hirayama with a kiss on the cheek in admiration and gratitude. There is also his runaway niece Niko (perhaps named after the Velvet Underground singer, Nico, born Christa Päffgen) who seeks refuge from her family and is a fast soulmate, and then her well-off mother who is his sister, and finally, the café owner Mama, played by the beloved Enka singer, Sayuri Ishikawa. Each suggests Hirayama’s possible fantasy (or what others project upon him) of some kind of romantic connection with someone. It’s the last of these relations, to Mama, that is the most pointed—in fact encouraged—and gives rise to the most expressive emotion in Hirayama, and not just for her. Hirayama feels for everyone, and it’s hard not to love him in return.

In her café, Mama remarks that a heavily drinking customer in the corner is rejoicing because he finally “got rid of” his wife. She nods ironically to Hirayama, who sits at the bar as usual, treated to tsukemono (pickled cabbage appetizer) she serves him while preparing his food. She’s easily coaxed into singing for the few men in her café that night, and accompanied by one customer’s guitar, she performs a Japanese version of “The House of the Rising Sun.” Her lyrics are telling, as is her soulful delivery. (In fact, the Japanese version of this song, as sung by Maki Asakawa in 1972, was a bluesy hit.)

Reduction in Production

Given the modern architecture of the Tokyo Toilets and Hirayama’s choice of a minimal habitat and lifestyle, and in light of his quiet poise as a subtle cover for his cultivated taste in music and literature and his acute visual perception, what approach to shooting the film would suit the character? Forget an elaborate plot and story arc. Allow clear and direct, simple and earthy songs to become the soundtrack of his life, present and past, replacing dialogue and backstory as much as possible. Let Hirayama’s bonsai garden and his black-and-white photographs of nature—whether in his prints or in his dreams—carry his beliefs and values. Then how could the mode of production could fit the film’s themes and style? Wenders reports to audiences how it evolved beginning with Hirayama’s abode:

We had an empty place. We chose that, and it was beautiful. And then the Art Department came with a truck and it was full of stuff. And then the two of us sent everything back. Koji (Yakusho as Hirayama) decided what he needed, and in the end, only the futon and the cassette and the books and the little table with the plants. Everything else we sent back. The Art Dept. was horrified, and I regretted some decisions, because there wasn’t even a chair for me to sit on, so I had to sit on the floor, which is, of course, fine in Japan.

We had 16 days with Koji…. So, we worked fast. We did 50, 60 set-ups. Because we had adopted Hirayama’s life into our shoot, and as he had reduced everything he owned, and reduction was the principle of his life and his decision, we realized we couldn’t make a movie that had all this stuff, so we discarded the dolly and the track and the steady-cam and the gimbal and the crane and just had a man with a camera on his shoulder, and that was what we had to offer in terms of reduction. And then we lived with a 16-day schedule which, in a way, was what the production needed. So, it worked, and to everybody’s amazement, we got it all done and we never were a day late, and if anybody wants to know how to do it, call me afterwards.

If anyone could structure a feature film relying on just the simple elements of music, architecture, and nature, that person would be Wim Wenders. The thoughtfully curated songs of Hirayama’s youth, classic rock and R&B from the ‘60s and ‘70s (the Animals, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, Van Morrison, for example), ingeniously edited into the film, narrate it more cogently and resonantly than any dialogue and carry the core of the conflict and feeling. Their narrative economy of quiet lyricism permeates the film and serves the 1:33:1 aspect ratio for the film’s frame, its boxy format more intensely intimate than an expansive perspective. Yet there came to be one more crucial decision in shooting Perfect Days.

An Actor’s Film

To carry the civic pride in the architecture, dignity of the work that supported it, and the compassion for the people it served, the film needed a human body, a sensitive face, expressive eyes. Kogi Yakusho, as venerated as he was familiar to audiences worldwide, welcomed the role before he had even read the script. Yakusho won the Best Actor award at the Cannes International Film Festival for inhabiting the character heart and soul. Still, what’s surprising is Wenders’ revelation:

He so much became Hirayama that, for the first time ever—I mean, I’ve made a lot of movies—but for the first time ever I suggested to the actor on the third or fourth day to drop the “rehearsals” (per se) and let me shoot them as the film itself. And he was a little bit amazed. Whenever we’d rehearsed, afterwards I thought, ‘If I’d only shot this!’ So more and more, we proceeded as if we were making a documentary on a very fictional character. He was totally fictional, but we were able to shoot with him as if we were following a real person called Hirayama. And that, of course, is completely unique, so he got the award for having created the film in his character.

In the end, we might consider that Perfect Days is seen not only through Hirayama’s eyes but also in his eyes—that is, in our gaze upon the kaleidoscopic countenance of an actor who plays his role as if, in crafting it, he were crafting his own life and didn’t need to be meticulously photographed by cinematographer Franz Lustig or scrupulously directed by Wenders. As the actor Koji Yakusho has said, “images that audiences see are burned into their eyes and can’t be removed or taken back, so it’s important to put your best into your every shot.”

A Komorebi and Tokyo Skytree

The Japanese language has a special name for these fugitive apparitions that sometimes appear out of nowhere: “komorebi”: the dance of leaves in the wind, falling like a shadow play onto a wall in front of you, created by a light source out there in the universe, the sun.

Wim Wenders

Each day when Hirayama drives to work, he is dwarfed by the phenomenal Tokyo Skytree. It juts out from the cityscape and climbs to the heavens as Hirayama looks up to the sun. It is said that the Skytree “stands tall, from the ground up, without hiding a thing—showing a virtuous, pure, and humble character.” Hirayama’s nightly dreams, though, are minute abstractions of light and shadow, also emblematic of the entire film.

Still, there is a scene that animates even the delicately dynamic concept of komorebi. Hirayama, excited to visit Mama’s small restaurant on his night off, accidentally catches her kissing a man at the door; embarrassed (and surely saddened), he takes off to buy a six-pack of beer and cigarettes to console himself at the water’s edge. Unbeknownst to Hirayama,that was Mama’s ex-husband, and he appears komorebi-like himself when he surprises Hirayama at the riverfront. Their whole exchange can be viewed as “a dance of leaves in the wind” under the exquisite multi-colored lighting of the Skytree; first they smoke and drink in tandem (each choking on the nicotine), and then they enjoy free play in an improvised choreography of “shadow tag” on the pavement. It’s a psychological thrill just watching their duet, two could-be adversaries in the game of love—each in his separate way a shadow in that game and a shadow of the other—actually commingling in their test to see if two overlapping shadows are darker than one. They’re not—each has agency, separately, even though one is dying.

How richly metaphoric—not only in their roles in the narrative at that moment (both “fugitives” from Mama and from life) but also in terms of cinema as an art form, itself shadows dancing in the light, falling onto a screen before us. It’s not difficult to look at the whole film, Perfect Days as a larger allegory of cinema itself, built as it is of: images (the komorebi—real, photographed, and dreamed—of Hirayama’s gaze); settings (the architecture of the Tokyo toilets); music (Hirayama’s audiotapes but also Mama’s performance); parallel segments of action with variation (the “to and fro” of work and its encounters, often “choreographed” duets such as Niko and Hirayama taking pictures in the park with the same motions on their same old cameras, riding bikes in tandem, spouting aphorisms as echoes ); and words (the dollar paperbacks Hirayama reads nightly, the Patricia Highsmith book he buys echoing Wenders’ own previous film, The American Friend—incidentally, about a dying man).

The final scene—a face and a song—is indelible. As Wim Wenders has said, “The whole film is in that last shot.” The acting is key, as is the camera: it starts with a close-up of Hirayama behind the wheel of his van, and without notice, the shot moves in on him, his interior being, just as the structure and the content of the whole film have, little by little, stolen their way into this tacit man’s heart as he enters a “new day”—and, as Nina Simone sings, it’s “Feelin’ Good.”

If anyone understands lyricism in today’s world, it’s Wim Wenders. To chart Hirayama’s life in his physiognomy, as if to map its light and shadow in the curl of his lips and the tears of his eyes, to chronicle a longtime sehnsucht and the joys of the moment, is to give us the entire film in a face, one so luminous from within that we all but forget how fleeting that cinematic experience actually is, and yet how infinitely memorable.

* The quoted passages above are chiefly from notes Wim Wenders has offered the press, and they are joined by excerpts from a post-screening Q&A with Wim Wenders and Koji Yakusho moderated by Jenelle Riley, Editor at Variety magazine, on January 11, 2024.

**Perfect Days is Japan’s submission for the 96th Academy Awards and is nominated as Best International Feature; on October 19, 2022, Wim Wenders was awarded the Praemium Imperiale, also known as the “Nobel Prize for the Arts,” by the Japan Arts Association.

Perfect Days

Producer: Koji Yanai, Wim Wenders, Takuma Takasaki; Director: Wim Wenders; Screenplay: Wim Wenders, Takuma Takasaki; Cinematography: Franz Lustig; Editing: Toni Froschhammer; Dream Sound Design & Re-recording Mixer: Matthias Lempert; Dream Installations: Donata Wenders; Dream Installation Editor: Clémentine Decremps; Production Design: Towako Kuwajima; Sound Design: Frank Kruse; Costumes: Daisuke Iga.

Cast: Koji Yakusho, Tokio Emoto, Arisa Nakano, Aoi Yamada, Yumi Aso, Sayuri Ishikawa, Tomokazu Miura, Min Tanaka.

123 min., Color and B/W. In Japanese with English subtitles.

Songs:

“The House of the Rising Sun,” The Animals, 1964

“Pale Blue Eyes,” written by Lou Reed, performed by The Velvet Underground, 1969?

“(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay,” Otis Redding, 1968?

“Redondo Beach,” Patti Smith, 1965

“(Walkin’ through the) Sleepy City,” written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, performed by

The Rolling Stones

“Aoi Sakana” (“Blue Fish”), Sanchiko Kanenobu, 1972

“Perfect Day,” Lou Reed, 1972

“Sunny Afternoon,” The Kinks, 1965?

“The House of the Rising Sun” (Japanese version) written by Maki Asakawa, 1972

“Brown-Eyed Girl,” Van Morrison

“Feelin’ Good,” performed by Nina Simone, 1965

“Perfect Day,” performed by Patrick Watson (over end credits only, piano only?)

The Tokyo Toilet Architects:

Fumihiko Maki

Junko Kobayashi

Kashiwa Sato

Kazoo Sato

Kengo Kuma

Marc Newson

Masamichi Katayama

Miles Pennington

Nao Tamura

NIGO®

Shigeru Ban

Sou Fujimoto

Tadao Ando

Takenosuke Sakakura

Tomohito Ushiro

Toyo Ito

Books:

William Faulkner, The Wild Palms

Patricia Highsmith, Eleven (containing the story, “The Terrapin”)

Aya Koda, “Ki Shinchosha”