5-6-11

By Diane Sippl

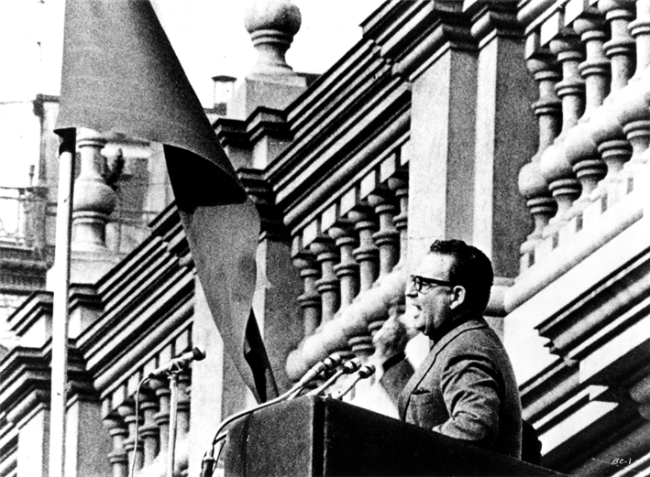

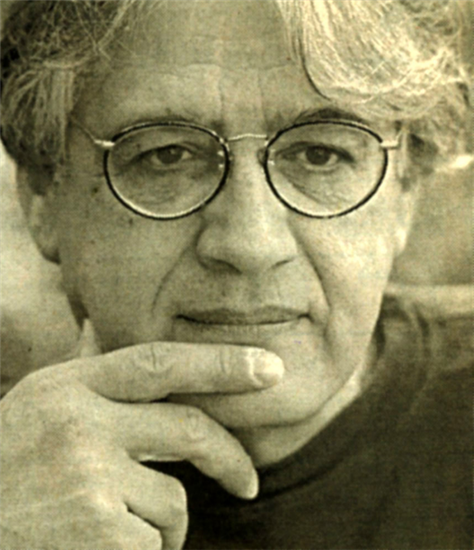

Salvador Allende in The Battle of Chile

“Patricio Guzmán: The Watchful Eye,” from April 15 to May 11 at the Billy Wilder Theater, is a stunning retrospective by the UCLA Film and Television Archive showcasing nine films by Chile’s renowned documentarist, Patricio Guzmán, from his first internationally acclaimed work, The Battle of Chile (1975-1979) to his latest award-winning film, Nostalgia for the Light (2010), which opened the series in advance of its theatrical run in Los Angeles at the Nuart Theater. Patricio Guzmán was scheduled to appear once, on April 29, when he held a lengthy discussion following Parts I and 2 of The Battle of Chile, but in fact he also attended on April 30 and held two separate Q & A sessions, one following The Battle of Chile Part 3 and another following Chile, Obstinate Memory (1997). The series continues with The Pinochet Case (2001) and Salvador Allende (2004) on May 6, The Southern Cross (1992) and A Village Fading Away (1995) on May 7, and Madrid (2002) and Robinson Crusoe Island (1999) on May 11. (For those so unfortunate as to miss any of these or who wish to re-visit them or recommend them, all films but for the May 7 program are available at www.IcarusFilms.com.)

The dialogue both nights, mostly between Patricio Guzmán and the audience, was introduced by Paul Malcolm, UCLA Film and Television Archive Programmer, and moderated by Verónica Cortínez, Professor in the UCLA Department of Spanish and Portuguese, co-presenter of the series along with the Latin American Institute. Spontaneous interpretation was provided by Leah Kemp. All photos are courtesy of Icarus Films.

Army arrests in The Battle of Chile

The experience of making the film marked us for the rest of our lives. Everything else is merely a figure of speech.

Patricio Guzmán, regarding The Battle of Chile

Socialist Review #35, 1977

All the love that was poured into the filming (and I believe that if you’re not in love with what you’re doing, you’re really not doing anything) is distilled into Part 3. What I experienced in Chile was an immense tenderness toward what was going on.

Patricio Guzmán, regarding The Battle of Chile

Socialist Review #35, 1977

Of all that could be said about Patricio Guzmán’s landmark films, I cite these two remarks he made to scholar Julianne Burton as she interviewed him in Havana while he was still editing his three-part, four-and-a-half-hour epic, The Battle of Chile: The Struggle of a People Without Arms because for me these words characterize the man and his stirring body of work, then and thereafter, more than any of his sobering footage of tanks and bombs, of a cameraman filming his own death, of a President saying good-bye to his country, of survivors bearing witness to torture. Guzmán experienced all of these numbing encounters, and more, in the midst of documenting Chile’s successive regimes, but his work has been a matter of analysis of oppositional perspectives, and not mere reportage, risky as the filming has often been for him and his crew. Beyond the chilling images, sequences that we can hardly call sensationalistic because they are real, are calmer ones of citizens talking, organizing, taking action, and finding new ways to shoulder responsibility, make decisions, take initiative, and endure. These day by day, moment-to-moment discoveries both promised and delivered a Chile never seen before, one that achieved a peaceful revolution, a transparent government, a true democracy. And a man with his hands clasped to a two-wheel cart behind him, running to pull it as fast as his legs could carry him, would find his shadow on a screen, the reels spinning celluloid through a projector’s light, carrying him around the world.

The Battle of Chile, filmed between February and September of 1973, has astonished international audiences — film critics and historians, political theorists and social organizers, anyone wanting to see, on the street level, how a coalition of diverse fronts orchestrated the non-violent transformation of a nation that was crushed by the disproportionate power and counter-revolutionary alignment of an arch-enemy. What spectators often find unbelievable and unforgettable in The Battle of Chile is the live broadcast footage of the Chilean Air Force bombing the country's Presidential Palace in a right-wing coup d’état; an Argentinian cameraman shooting film of Chilean soldiers as they shoot bullets at him until he dies; the subsequent arrests of four of the five members of The Battle of Chile’s crew who were, in the case of Jorge Müller Silva, missing forever after being interned at the torture camp Villa Grimaldi, and in the case of the others, irretrievably exiled. Guzmán himself was held for two weeks in Santiago’s National Stadium before he fled his beloved country.

The Battle of Chile

Yet The Battle of Chile’s purpose, method, content, and form were invested in and attuned to Chile’s unique moment in history and already embodied Patricio Guzmán’s singular lyrical voice as an incomparable cineaste. Was the filmmaking process “collective, guerrilla, clandestine” — the labels slapped on “revolutionary” filmmaking? Not really, given Chile’s unprecedented turn of events that led to a democratically elected popular government whose filmmaking processes were sanctioned by law and also to a crew so tiny its close-knit members could communicate by whispers, glances and hand signals so as to be as unobtrusive as possible amidst the activities they were openly recording. The film’s approach was not agitational but dialectical; it was neither “objective” nor “biased,” but analytical, deliberately juxtaposing Chile’s prevailing, pluralist factions so as to document the country’s strides and conflicts alike.

The audience at UCLA’s

retrospective wanted to get the facts “right” from someone who has devoted a

lifetime to discovering, experiencing, recording, and digesting Chile’s

tumultuous history. Many of their

answers were

yet to come, in the shocking truths disclosed in The Pinochet Case and the tragic, piercingly elegiac Salvador Allende, discussed in tandem with Nostalgia for the Light in the reviews section of this magazine.

Guzmán’s mode of address at UCLA, a dialogical exchange, should come as no surprise. While today’s Los Angeles audiences are used to the post-screening Q&A format, the extent of Guzmán’s interaction — nearly two hours, spread across three sessions on two evenings, and offering considerable scope and depth — is a testament to the filmmaker’s wealth of knowledge and lived experience, his eagerness to stimulate discussion, and his patience and diligence in fielding a barrage of questions. The talk that transpired is unedited here, in order to sustain the spontaneous chain of reactions and the spirit of the rapport, occasionally with spectators who recall the times and even the film as it was first shown, or in fact lived in Chile and suffered in the coup’s aftermath. No questions have been omitted, because even when beyond the topic at-hand, they are telling indicators of today’s modes of reception of the films and their history; thus they serve as another layer of documentation. The Q&A process lent itself to Patricio Guzmán’s keen dialectical mind, one forever turning an answer into a new question while refusing to forget the original issues at stake. The event, then, pointed to the possibilities of cinema as a tool for communication, a means of participation, a vehicle for engagement that makes us who we are.

The Battle of Chile

April 29 — The Battle of Chile, Part 1: The Insurrection of the Bourgeoisie and Part 2: The Coup d’Etat

Verónica Cortínez An American film critic described the structure of The Battle of Chile as that of “the iron structure of the Greek tragedy” — would you agree with that, and in what sense?

Patricio Guzmán From any way you look at it, Allende’s period can be considered a Greek tragedy, so I do agree with that.

VC Because from the very beginning of the movie, over the credits is the sound of the airplanes and the bombardment, so we know there’s no way out.

PG I put the airplanes and the bombs falling right in the opening credits because this gives an idea of what’s coming, and then we go into everything.

VC It says in the credits that this is a revised version. Could you talk about that?

PG It’s ‘an updated version’ because about seven years ago I took about twenty-five words out of the text. I took out the words ‘imperialism’, ‘bourgeoisie’, ‘fascism’ and I replaced them with ‘White House’, ‘Washington’, and ‘middle class’, and I didn’t use ‘fascism’ as many times as I did in the first. I’d used those words a lot in the first version, which gave the film a redundancy. And I took them out only for that reason.

Audience Member You say that the film takes the form of a Greek tragedy in that there’s no exit, since the first shot is of the planes and they’re already attacking the Presidential Palace. But at the same time, once the film starts and we see people in the street, there’s an incredible sense of hope, though it seems that the options diminish over time, and we get a sense of the walls closing in. As you lived it, was it your impression that there was no exit? Were there moments when another outcome seemed possible? Did you feel that President Allende made decisions that maybe affected the outcome?

PG One never loses hope. Even at the end, at the worst moments, when the right wing… the question was hope or naiveté, right? And it was hope, and the situation could have changed, though it was difficult. We were four young people who never lost hope.

When a film like this is edited afterwards, of course you already know what happened.

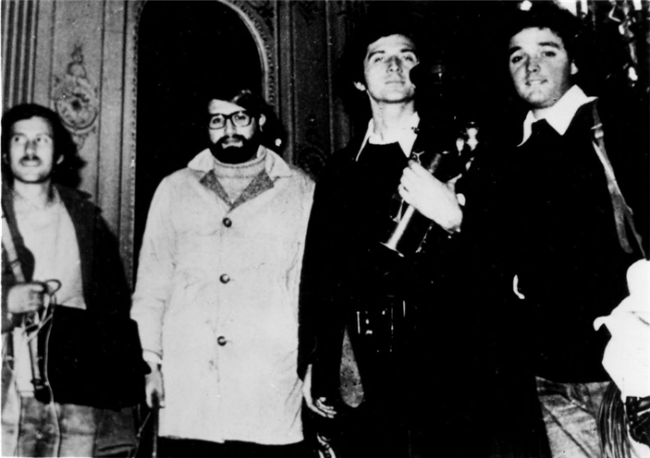

El Equipo Tercer Año, the production team for The Battle of Chile: sound technician Bernardo Menz, director Patricio Guzmán, cameraman Jorge Müller, and production chief Federico Elton

AM I saw this movie when it came out about thirty-five years ago, and I’ve remembered it as a very powerful but also a very analytical movie. Yet even now I’m really struck by the level of emotion in it, and I’m wondering how you chose for that mix of emotion and analysis.

PG The first part of the film follows a structure of chapters — the legislative boycott, the strike. And the second part is just one sequence. The structure is one that we thought about for four years; that’s how long the editing process took us. And also it was the structure we used in the script, an outline of reality. We didn’t film spontaneously. We were selecting the points where the class struggle was focused. It’s an immersion in a crucial period. It was the first time in Latin America that a social process was filmed day by day, with a unity of style that didn’t exist in Latin American cinema. I’m sorry that Bolivia hasn’t had its Battle of Bolivia.

AM You mentioned four people making the film, but technically, from moment to moment, it seems there was a lot of freedom in handling the camera. Were you over the shoulder of the camera man? How were you were directing?

PG He had freedom of action, but not a lot. When one is young, one wants to control everything. Now I give a lot more freedom to the camera. I’m more secure. But this was my first important film, and I wanted to be on top of everything. I stood behind Jorge Müller on the left side, because the camera was on the right side, and it covered his ear, and I told Jorge, ‘A truck is coming. It’s going to come from there. When it comes in, follow the truck. And you’re going to run into a march coming down the other street. Stop there. Follow the parade’.

Our dream was to do sequence-shots. The documentary film is a genre that is very fractured. You cut a lot to keep to the structure. We wanted to take advantage of the rhythm of the masses to do long shots. Sometimes we managed it, and sometimes we didn’t, but that was our desire.

All in all, there was a great affinity between Jorge and me because we had the same aesthetic. The sound man had to be next to us all the time. There was no particular direct sound. The sound man had to be very loyal. There were high-risk moments, but he never stopped recording. And when you have a crowd of people that surrounds you, you have to lean down so that you don’t trip over the cable. Or if the camera falls — we had an Eclair that was very good, but very heavy — when it falls, the focus is lost and you have to repair it. And we didn’t have any other camera. We had one microphone.

Celebrating Chileans in The Battle of Chile, © Poirot

AM In the United States right now, unlike in The Battle of Chile, workers don’t identify with each other. They identify with Donald Trump, and with rich people they see on television. What you might do as an artist, or what do you think culture might do, to change that?

PG No idea.

AM What relation does your film have with Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers?

PG The fiction film? None at all. Apart from the name — none. We discovered our title during the copper strike when there was a disturbance in Santiago. It lasted a long time. We called that ‘the Battle of Santiago’. And we thought, there’s the title, The Battle of Chile. And then the subtitle, The Struggle of a People without Arms, was taken from a book by Marta Harnecker. It had nothing to do with Pontecorvo.

AM If it wasn’t The Battle of Algiers, what were some of your inspirations, and especially, when you began the film, what did you think you were filming or creating?

PG I was in Spain for six years before that, and to make the film is why I returned to Chile. I arrived in March of 1971, and I was so motivated by the popular disposition that I was interested in making a film about that. It was a moment of political foment, of democratization, of participation, of enthusiasm. Poor people had never come to the center, and it happened for the first time. It was a time of euphoria. There were people who walked in the streets laughing to themselves, so happy to be Chilean.

And I was so lucky to see a country in love with its President that I thought it was necessary to film right away. During filming I wanted to show this mobilized and enthusiastic population; I never lost sight of that feeling.

VC When you went to study in Spain, did you want to become a fiction filmmaker?

PG I was interested in documentary filmmaking before going to Spain, but there aren’t any specialized schools for documentary. You have to go to a fiction filmmaking school; there’s no other alternative. Yet I preferred the documentary even before I went. I can give you eight examples: To Die in Madrid by Frédéric Rossif, the first film about the Spanish Civil War; a more frivolous film, European Nights by Alessandro Blasetti; World without Sun by Jacques-Yves Cousteau, and his first film, The Silent World, that he also made with his spouse, Simone; a film by a German named Erwin Leiser that was called Mein Kampf, the first comprehensive documentary of Nazi Germany; The Living Desert, produced by Walt Disney. I could see them in a theater on Picasso Street. These films told me that this was the type of film I wanted to make, films about reality. Nevetheless, I went to film school and learned how to direct actors, but I wasn’t interested in all that. The more you know the better — camera position, camera movement, the basics.

Augosto Pinochet in The Pinochet Case

AM Do you feel that Kissinger and other U.S. officials should be judged in an international tribunal?

PG It’s correct to say that they treated Chile in a criminal manner, but there was a large part of the Chilean middle class that pushed for Allende’s overthrow. If Kissinger and Nixon had not existed, the government would have held on longer, but it’s not at all certain that it would have triumphed. The Chilean Army had few loyal officials. There were six or seven officials in the high ranks who loved Allende, but a large number detested him, so the coup d’état could have happened anyway. The U.S. had already killed the only official who could have controlled the situation, René Schneider, Commander-in-Chief of the Chilean Army. The U.S. killed Schneider at the same time that Allende was elected, and that was fundamental; it’s absolutely clear. He was an extraordinary person and he could have contained the Army, but he was taken off the map. We can’t say that the definitive responsibility lies with the United States, with Kissinger and Nixon, because a big part of it was in Chile. But they sped up events, though Allende’s government could have fallen anyway.

Chile had a peaceful revolution — something that was completely new in the world. Allende did not like the idea of a single party. He didn’t like a dictatorship of the proletariat. He was an atypical Marxist, so he had more difficulties with his own coalition. There were many difficulties to overcome. I understand your argument, but I can’t support it as an absolute.

AM Did Allende commit suicide, or was he killed?

PG Allende committed suicide. It was a political suicide, and it’s exactly the same, whether he was shot or he shot himself. The true crime was bombing the Presidential Palace with the President inside it. That’s what should be judged — not exhuming his body in the first place; but secondary is the distraction. It’s important to judge the ones who carried out the disproportionate coup. There were no arms in Chile.

A Street Demonstration in The Battle of Chile

AM With the last question exposing so well why the workers needed, in fact, to be given arms, to defend not only themselves but really the government, my question is why Allende didn’t, somehow, provide those arms to the people. Maybe he just didn’t have them. Or did he trust the Army too much and believe that it would be on his side, and play a little bit naïve in that respect?

PG Allende was anything but naïve. He was a great negotiator. He was very astute. He was a seducer. He went into the lion’s den. He thought he could control the Army from above, and he almost did. If he had armed a group of workers, the Intelligence Service would have found out about it the next day, or if he had started training people in a field somewhere, the military would have found out about it. And they would have said, “What! This wasn’t a peaceful revolution? You were arming a parallel Army?” There was no tradition of clandestine operations in Chile. It wasn’t in the culture. Everything was talked about with open doors.

There are two types of leftist parties: parties of the masses and of specific people. All the parties in Chile were of the masses. And it was hard to maintain their behavior; it was almost impossible. Everyone knew what every other cell in the Party was talking about. The biggest sport in Chile is politics — debate, exchange, contradictions — that’s the national passion. They do other things across Latin America — dance, enjoy popular culture. Allende created a plural Left based on Chile’s nature. The problem of weapons is very obvious, very rudimentary. Allende knew the risk he was taking. That’s my opinion.

AM You said earlier that there was a moment in time when his government could have succeeded. Would you elaborate what those moments were within the context of what you just said now? What would have happened? If there were moments when Allende could have triumphed, what were you thinking about?

PG After the rehearsal coup on the 29th of June, three months before the coup, Allende said from the balcony of La Moneda that he was going to call a plebiscite. If he had called it a week later, the entire Left would have worked with that, and I think he would have won, but that was an escape valve. They were going to ask whether or not to change the Constitution. There were companies that had been expropriated that the Right was going to say should not have been expropriated.

The other incredible moment was when General Prats, the principal, leading general, resigned, and Allende left him alone, without any contact with the Army. Perhaps Allende should have said, “General, please don’t resign.” That would have won him some time. He was an expert at buying time, and that irritated the Right. General Prats resigned because the wives of the other generals went to his house and threw corn at him, which was a way of calling him ‘chicken’.

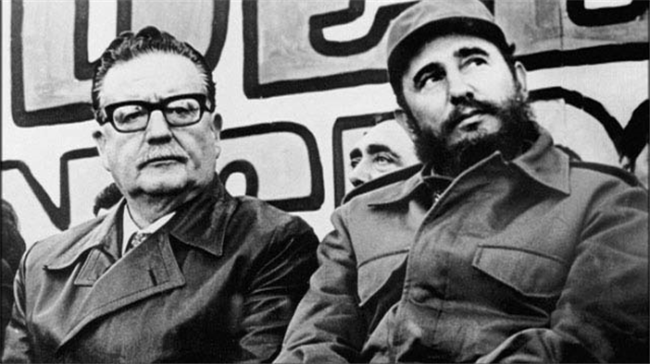

Salvador Allende and Fidel Castro in Salvador Allende © Prensa Latina

AM I remember in the first seven months, the MIR people and some advisors from Cuba were asking Allende to use guns if necessary, or at least to have a trained militia, but even earlier on, he was so clear about this, that he would never accept this as a strategy. Is that how you remember it?

PG Yes. The arms did arrive from Cuba, and there were several boxes with weapons that Allende hid in the basement of La Moneda. And it came out in the newspapers that Fidel Castro was sending weapons to Chile, but that was a poisoned gift. Allende hid them and didn’t use them. The day after the coup, the military took them out onto the patio to show that Allende had hidden them in the palace, another tragic element of the story, because Castro had tried to help, in his way. The Soviet Union turned its back completely because it didn’t trust Chile: it was a piece on the chessboard that wasn’t good for the Soviet Union.

April 30 — The Battle of Chile, Part 3: The Power of the People

VC Patricio, yesterday we were describing the structure of the first and second parts of The Battle of Chile as in the form of the Greek tragedy. Obviously this part is sort of a break from the circle.

PC I want to explain that the third part of The Battle of Chile is not chronological; it’s not a continuation of the first and second parts. It’s telling the same story but in a different way. Part 3 has a type of material that’s different from that in the other parts; it’s material with less tension. It’s a description of small actions, not big events — the simple people who built small organizations. When we did the editing, this material was left aside. It didn’t fit in Parts 1 and 2, because when we put it there, it produced a stop in the action. It swelled it, and this was bad for the structure. So all of this was left out, and for a long time we thought we were going to have to eliminate it. But there was something in the material that made us look at it again, and we reached the solution of interweaving it as a demonstration of organization.

It’s very nostalgic material. What is shown is very fragile, but at the same time it has great value, because it’s popular instinct at work. For that reason it doesn’t have the same solidity as the first and second parts. I thought about using it as an annex and to start with a written text that explained this, but in the end we left that off and left the film as it was.

VC It doesn’t need it.

PG Maybe not.

The Power of the People in The Battle of Chile

VC At the very end is a person who speaks quite dramatically. He’s a well known actor. What is the function of Ernesto Malbrán, and how did he make it into the movie?

PG That’s a very interesting question. Ernesto Malbrán at that time was a political leader. He was coming out of the university where he had been a student leader. And in the time of the Popular Unity he went to the North, to the nitrate mines, and that’s where I found him, by chance. I didn’t know he was there. And then when I made Obstinate Memory I used him as a character, after Battle of Chile. Later he became an actor, as we know him now.

VC (To the audience) He plays the priest in Machuca — I don’t know if you saw it.

AM Can you tell us how the film was taken out of the country?

PG The Swedish Embassy saved the material, and my Uncle Ignacio. I didn’t keep it at my house; it was very dangerous. Every week I went to his house with eight to ten reels and we kept them in a room in his house that had a large trunk. When the military searched my home five times, they took a lot of things — other films that I had, photos, but they didn’t find anything from Battle of Chile. My first wife had a group of friends, and they knew that if I was arrested, they had to take the reels to the Swedish Embassy. I had contact with the Swedish Embassy through a Chilean filmmaker who was married to a Swedish woman; she was secretary to the ambassador. This filmmaker is Sergio Castilla and his wife, Lilian Indseth, has passed on. And when I made Obstinate Memory, I went to talk to Lilian, so that she could tell me how the material got into the embassy, and how the ambassador reacted, how they took care of the material. This was in 1997, and she didn’t want to talk about it because she thought it was dangerous. Even twenty years later there was still fear.

Since she didn’t want to talk, I found the driver who took the material from my uncle’s house to the embassy. And the driver was going to tell me, but he told me that he had to ask the embassy for permission. But the ambassador, in 1997, did not give the permission. That indicates how fear fixed itself in Chile. I would like to have had his testimony also, especially since Lilian died.

So the only person who talked about this was my Uncle Ignacio — in the next film you’ll see.

VC If I may add a note — you might not know — I wrote a book on Sergio Castilla, the filmmaker, and he told me this, that his wife had saved The Battle of Chile, and that she didn’t want to say it. So I have a very short note in my book telling this story, though she didn’t want to admit it.

PG The material was sent by boat from Valparaiso to Stockholm. At that time the first oil crisis happened, and the boat took much longer than usual to reach Sweden because of the fuel. And I went to Sweden to wait for the material with Federico, my production manager. We saw the boat arrive at the docks but we didn’t go aboard. We had to wait for the material to be sent to the Film Institute. We went to see the director of the Swedish Film Institute. He took us down lots of corridors and stairways to the cellar. We reached the room and there was no furniture, just the material, in the middle of the room — a small mountain of reels. Instead of thanking him for taking care of the material, we started to count the cans to see if anything was missing, but nothing was.

Bodyguards and car in Chile, Obstinate Memory

AM First I want to thank you for your most recent film, Nostalgia for the Light, one of the most beautiful films I’ve seen. But then please tell me, what was the nature of your working relations with ICAIC? Did you have a working relation with the institute even before you began filming, or did that come after?

PG I had no strong relationship with Cuba. Like everyone, I admired the Cuban revolution, but I had no link to ICAIC. It was Chris Marker who made the connection. He asked them to help me. Since I wasn’t a member of a party, if it hadn’t been for Chris Marker, I wouldn’t have gotten there. Once the link was established, I traveled to Havana for six months. And then I stayed six years. I went first alone, but then my first wife came with our two daughters. And I took the editor, Pedro Chaskel. Before leaving Chile, I had spoken with Pedro; I asked him if he wanted to edit the film, and he said yes. And I told him, ‘When I have the economic conditions to do so, I’ll call you.’

In Havana I called Pedro, but in a very special way, because you couldn’t call Chile from Cuba. And he arrived in Havana with his family. And it took us four years to edit the film. ICAIC behaved very well. They gave us all the time we needed, and they never got involved in our work. There was no pressure. They left us alone. They were a bit concerned because we were taking a long time, but they hung in, and they accepted the delay. I left Cuba in 1978 and I toured the world with the film. And I decided to stay in Spain.

After The Battle of Chile I experienced a very strong personal crisis and I was hospitalized. I was hit with a depression after the coup, but it was delayed, because while I was working on the film I felt happy; but once it was done I didn’t know what to do with myself. I’d lost the issue — it was the country. Exile and getting back to yourself takes nine or ten years off your life. You lose that time. It’s not a total loss — it’s an experience; but you lose that time. As time passes, you’re happy because of it. You might feel ten years younger.

AM Thank you for a very important film. I was particularly struck by the level of political sophistication of the workers and peasants. Can you say something enlightening about the methodology, of how the political education was a process in the struggle there?

PG During the editing process in Cuba, sometimes Cuban directors came in to see our work, and they were astounded at the political level of the Chilean workers. They said to me, ‘Here we’ve had a military revolution. We have one party, and we have a very large enemy. That makes our revolution very defined, very clear. But your revolution was highly reflexive. It was an experiment that you carried out, a plural Left with various positions, and that is so interesting to us. We couldn’t have done that, because the revolution would have ended. We have a very strong enemy.

I think this film shows one hundred years of political life, one hundred years of work on the part of leftist parties that little by little built this political culture, which comes from the last century and began in northern Chile in the saltpeter mines. That’s where the workers’ movement started and the workers’ process began; that’s where the Communist and Socialist parties began. Chile had the first popular front in Latin America in the 1940s. It was the third popular front in the world, after Spain and France. All of that political culture expressed itself in the Popular Unity, and Allende was a product of that movement. He started working when he was eighteen years old in the university and worked through the entire political history of the country.

VC Do you think that today the workers’ movement has the same level of politics?

PG Unfortunately that was lost forever. Maybe not forever, but it’s going to be very difficult to reconstruct that social fabric. It’s a big setback. But we have to start again.

AM After the first important tour you did, things seemed to go very quickly. Did you need to anticipate what was going to happen, in order to be there and film the events? How did you gain access to all these important meetings? And also, in hindsight, do you think there was anything you couldn’t capture that was also important, but you just couldn’t catch it?

PG Surely, there were many things we missed. We were a very small team. We were in Santiago. We traveled a bit to the South and the North, but very little. If we had had more material, we might have done a fourth and fifth part. There was such a historical acceleration, there was a lot to tell. In the countryside there must have been extraordinary things happening, but we couldn’t cover it. Much more could have been done.

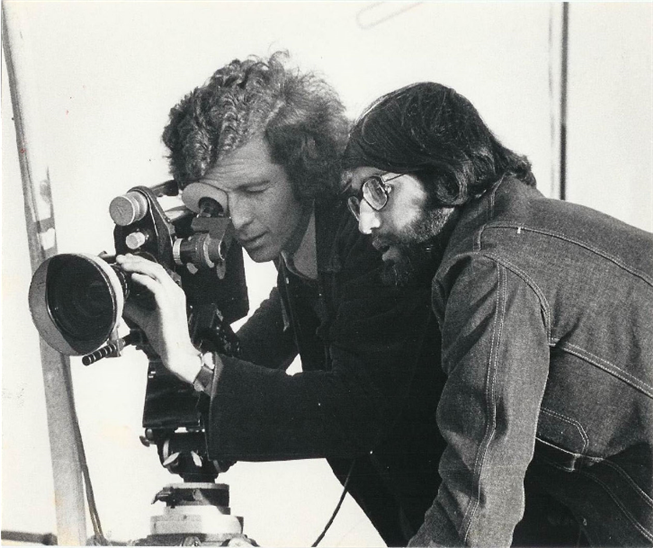

Jorge Müller and Patricio Guzmán

AM When you were working on the film, were you at any physical risk from the right-wing sources?

PG This film owes itself to the specific nature of revolution. There was liberty to film everything. We could film the struggle between classes in the same way that we shot the landscape. There was a state of law. We could circulate unharmed. There was no problem. But there were certain risks, particularly when we filmed the Right. Some right-wing groups were very violent. The truckers, for example — once a group of guards for the truckers with helmets and clubs encircled our vehicle and forced us to go to a camp for the neighbors. We had a very bad time. But a right-wing deputy appeared and told them, ‘You’re worried about this small group of journalists? Let them go, because you’re distracting the guards from this entire camp!’ That man saved us, and I don’t know what it means. I don’t know if he did it on purpose or not. They probably would have beaten us, but the problem was that they would have destroyed the camera, and there was no way we were going to get back a camera. We did have some more or less difficult situations, but not many.

At the end of the film it was

more difficult. All of the joy at the

beginning was transformed into tension.

In the last days we were working more under obligation than desire. We were afraid. We talked less and less. We were driving in the small car we had, yet

we didn’t speak. Aside from that,

nothing more serious happened.

April 30 — Chile: Obstinate Memory

VC I noticed that you dedicated this film to your daughters. Why?

PG Because they helped me to work on many other films before, and when I finished this film, I felt it was for them. I was thinking it was for all the young people in Chile.

VC Did it help you get over your original personal crisis?

PG No.

VC Which film helped?

PG One is always in crisis. Crisis is part of life. Perhaps with Nostalgia for the Light, I’ve calmed down.

For sixteen or seventeen years, we’ve done a documentary film festival in Santiago de Chile with a group of women directors. At first we had 50 viewers, and now we have 12,000. The four documentarists who are with me got married and had children. I had to change my team, but they’ve come back. We’re very happy to show in Chile documentaries that otherwise would not have arrived. My wife and I in Paris make the international selection, and we take to Santiago a great number of European, Canadian, and North American documentaries. Since the television doesn’t show this type of auteur documentaries, it’s a way for the young people to know what’s going on in the world.

What’s also been extraordinary is that now there are 30-35 young and not-so-young directors, the majority women, and they’re making better documentaries every day. At international festivals they’ve won prizes, and documentary production is now secure. That’s very stimulating.

I’m taking several well-known figures to Chile, many producers and filmmakers from Europe. There’s a great exchange between the Chilean group and the world.

VC That must help you with your crisis a little…

PG Maybe.

The Pinochet Case

AM It’s 35 years later and the elected leftist presidents in Venezuela and Bolivia look as if the whole process that you and your comrades started in the ‘70s manifested in this period. What do you think about this period of democratic socialist government power? And when you went home, when you went back and saw your friends, how were they building their lives in order to go forward at this particular point? And what do you think of the mixed economy in China?

PG I’m very happy that Latin America has democratically elected governments and that some of them want to make social changes. There are more chances now to come out of the backwardness. And about China, I don’t know what to say. I’m a filmmaker; I’m not an expert in international politics. I prefer filmmaking questions rather than ideological questions. This film works because it’s poetic, because it has emotion, which distinguishes it from other documentaries. That’s my specialty.

AM Okay, from the political to the poetic — do you still read or write science fiction, which is an uncensored form of literature, and philosophical and poetic (it can be)? It seems like this film, more than any of them, deals with the idea of the fragment, or the mirror inside the brain — that history implants itself and that you spend almost your whole life unraveling it. The movie seems to reflect that, as it sometimes happens in life.

PG It’s very interesting. Memory is a mysterious phenomenon. I’ve never studied it scientifically. I have friends who are psychoanalysts, doctors, who have spoken to me a lot about memory, but in this film I used only my filmmaking instinct. Many people, in order to live, forget. Allende’s widow herself says that she wants to forget. She can’t take it any more. She’s tired.

There are other people for whom memory helps to live, which is the case of Ernesto. He has all the strength he had when he was young.

And then there are the young people, who are the ones who suffer the most in this film. The lack of information is worse than amnesia. They don't even have the option of forgetting, because they never even found out what happened. That’s terrible. But little by little we have made progress.

I wanted to be a writer when I was very young, but I realized I wasn’t good, and I left it.

Hortensia Bussi, the widow of Salvador Allende, in Chile, Obstinate Memory

VC But you do have a movie called, My Jules Verne, right?

PG Yes, I do have a documentary about Jules Verne. It’s very helpful to know how to write a bit to do the commentary.

AM Thank you, again, for coming to Los Angeles. My question is about the times that you showed the films to the audiences, in particular the students. I’m interested in how you set those up. Did you tell them it was going to happen? Did you surprise them with the camera in the room? Please tell us a bit more of how it went. Those sessions were great.

PG The idea for the sequence came when I suffered the same thing. I gave a course on documentary film in a film school. And I showed The Battle of Chile, and when it was over, everyone was crying. I was very surprised. I didn’t think the response was going to be so dramatic. I thought that if I called other schools and repeated this operation, I could have some good material.

I called many schools, and the principals said it wasn’t good to do the screening, that schools thrive on the future, not the past. Showing this type of film was going to create a lot of grief, and they were in favor of moving into the future. It was the same response from men as from women in the schools. We went a long time without finding the schools. I even thought that the sequence wasn’t going to be possible. I thought about filming the phone and me calling, and taping them saying, “No… No… No…”

In the end we got four or five schools, and we were able to do the sequence. One is a Catholic nuns’ school, where you see the teacher who says she was wrong, and the others were public schools. The last one, where they were crying the most, is a theatre and pantomime school.

Madrid

AM Your personal story is hardly in the film. Why did you choose to omit the part of the story about how you got out of the stadium? Why did you survive, and how were you able to leave Chile?

PG I don’t know. I thought my sequence had to be short. It’s complicated when you start to talk about yourself. In a self-referential film, you have to measure that a lot. I give my life in bits — a bit in Jules Verne, a bit in Nostalgia for the Light, a bit in Madrid. And that’s why I didn’t want to stretch that sequence.

I’m very sorry that I didn’t lengthen the sequence with the doctor. That interview was done in a corner of his house. On the other side of the room was his entire family, four daughters and his wife. And when the interview was over, they all said to him, ‘Papa, you’ve never told us this story.’ That tells you that in 1997, people hadn’t yet begun to confess. And I didn’t film that, which was a serious mistake.

AM Are these films available in Chile?

PG There are many copies that are circulating within a group of documentarists. At the end of this year we want to put out a collection of the entire body of work on DVD. But I don’t think there will be more than 1,500 copies, a small distribution. Yet this will probably stimulate piracy, and that’s great, in this case.

AM I want to know if you think that eventually, for historical value, there might be a film on what happened after Allende died, the period when Pinochet took over. There’s probably not lots of actual footage, but would there be any interest in re-creation, or is there any footage to talk about what took place after, during, the dictatorship — to make a film about it?

PG There are two filmmakers, very valuable people — Pablo Sales is one of them — who filmed the entire repression period. Sales filmed the repression in Santiago for years and years. A great film could be made with that footage, without a doubt. But it hasn’t been done yet. There are many events that they filmed very well, but no one has taken that material to do a long work.

VC But you know that we’ll be seeing the film, The Pinochet Case in the part of the program coming up next week.

Jorge Müller

AM I want to use the opportunity to pay my respect for all the people who were humiliated, tortured, and killed in that period of time. I was lucky to survive what happened… Well I’m Chilean, and during that time, I, also, was arrested. I was confined in a special camp. Fortunately I’m alive. Many of my good friends are missing. I definitely want people to appreciate your work to prevent history from being forgotten. I have many questions, but I prefer to let the rest of the audience ask questions.

AM I understand the focus on the socialist culture in Chile. Yet there’s one thing that I thought was missing. Are there any vestiges of indigenous culture left in Chile such as we see in Bolivia now?

PG I’ve explained that we had little material in filming The Battle of Chile, and we did not film in rural areas — very little — and we never went to the Mapuche territory, for example, where there was a strong popular uprising. That event deserved a great film on its own. They were victims of terrible repression, and I couldn’t film it. The Mapuche territory has always been very conflicted, with great social combat, even now. The coalition governments prohibited filming there. A young woman documentarist was arrested for going to film there. Her name is Elena Varela. She was arrested by the police and accused of being a terrorist. All of her material was stolen. And then the police used the material to take as prisoners the people she had interviewed. It was a huge scandal. And it came out later that she had no terrorist background. She was in prison for a year before she was released. After two or three years, under Bachelet, it came out that she hadn’t done anything.

Patricio Guzmán

AM Could you talk a little about your classes and your process of choosing your subjects? I just saw your other film, Nostalgia for the Light, and all your interviews are so incredible. How do you choose people for your interviews? Do you start with a lot more people than end up on the screen? And also how much time you spend with them, and how you get to that point that your movie is so emotional?

PG Interviewing is a true art. You learn it very slowly. The first thing is to give all the necessary importance to the person being interviewed. Never stop looking at that person. Don’t look at the papers that you have with you — don’t have papers; memorize your questions. The camera has to be very attentive to everything that’s happening. No noises. You have to look for the right place. You have to avoid anything that can be distracting — a painting or knick-knacks that would be bothersome. The interviewee has to be well lit and you have to make yourself invisible. The way you do that is by focusing all the attention on the person speaking to you.

You never push toward the responses that you want. You have to do the opposite. You have to begin very far away. I start by asking, ‘What did your father do?’ or ‘What’s your mother’s profession?’; ‘How many brothers and sisters do you have?’ Then I start to get closer to the issues that we’re interested in, but very slowly — moving in circles. You have to respect the silences, and also respect the errors.

You have to transform the interview in a cinematographic space. You leave journalism and move into a sequence. That’s very important, because in film there’s more room for words, and in journalism, practicality reigns. Questions, questions — you have to motivate the person to speak on his own. There are even people who start thinking. That’s ideal.

In interviews, directors tend to think that they are dominating the situation, but it’s the other way around. The interviewee realizes if the director is nervous or not, and sure of himself or not, and realizes if the cameraman is good or bad, the sound man, too. The interviewee knows more than we do. You have to take that into account. When ending an interview, when you say, ‘Thank you very much for the interview,’ you have to continue filming, because that’s the moment when they’re going to say the best thing.

The Battle of Chile: The Struggle of a People Without Arms

Director: Patricio Guzmán; Screenplay: Patricio Guzmán, Pedro Chaskel, José Bartolomé, Julio García Espinosa, Federico Elton, Marta Harnecker, Chris Marker; Production Manager: Federico Elton; Cinematographer: Jorge Müller Silva; Editor: Pedro Chaskel; Sound : Bernardo Menz.

Voice-over narration by Patricio Guzman.

B/W, DigiBeta, 262 minutes. In Spanish with English subtitles.