3-9-14

3rd Los Angeles Turkish Film Festival: Atalay Taşdiken’s Meryem

By Diane Sippl

I was ruffling the pages of film books a few days ago. I took some of the books that I had read years ago and comfortably sat on the sofa. I came across a sentence that I underlined as I was turning the pages of Tarkovsky’s Sculpting in Time: “The image is an impression of the truth, a glimpse of the truth permitted to us in our blindness.” I thought about this sentence for awhile. Then, in the light of Tarkovsky’s words, I pondered over the films that we’ll be screening…

It is amazing to be cinema’s student. It is amazing to learn with films and watch films as if we are dreaming…

Cenk Ertürk, LATFF Director, “Festival Introduction”

The catalog for the 3rd Los Angeles Turkish Film Festival, held March 6-9, 2014 in Hollywood’s stunning Egyptian Theatre, is as impeccably mounted as the rest of the event and showcases the commitment of a festival director who brings a high degree of professionalism in presenting a national cinema to an “industry town” that needs to expand its horizons. But Cenk Ertürk also brings something else, something quite exceptional in the increasingly inundated turf of film festivals popping up like mushrooms after the rain: the ever studious expertise of a film devotee who is dedicated to the art of cinema. Believe it or not, how rare that is in Southern California today!

So in congratulations to him and his bravely artful celebration of the latest results of Turkey’s longstanding contribution to world cinema, let’s acknowledge our “blindness” as we enter the dark theatre prepared to glimpse new “impressions of truth.”

In some ways, like no other, Atalay Taşdiken allows us to “watch films as if we are dreaming” when we turn our eyes to his Meryem.

In the turquoise luminosity of a vast lake are reflected heaven and earth alike, clear spring skies and a mountain peak that open the vista of a young maiden who awaits her future. She sees only its promise. Our first glimpse of her, in a flowing white gown with a man at her side, perched on a precipice looking out on the water with her expansive point of view, delivers us to a dreamscape of ethereal light.

Nearby on a dry plateau in Anatolia, Eflatun Pinar, a “lilac-colored spring,” rises up from the ground, creating an oasis and fountain. It produces an astonishing amount of icy clear water before it falls to the vast lake below. At this ancient sanctuary, deities of the Hittite Pantheon, flanked by figures wearing a winged sun disk, are carved into a wall of huge boulders that stands upright after more than three thousand years. The goddesses, as if alive and in full power, gaze out from the stone relief to deliver the promise of the old belief: a woman who bathes in these waters will find herself with child.

Into this bath, to assuage the customs of the local women, the adolescent bride Meryem is submerged as if to shock her into fertility. It’s more like a ritual sacrifice to the gods than a session of physical therapy, because at home she is bedridden with fever from the impact of the icy waters. If only her newlywed husband would send for her to commence their conjugal life, she could please everyone by bearing a child, but since he returned to Istanbul within a week of their wedding, which was only a few days after he was called there to meet his new fiancée, the best she can do is fulfill her marital duty by serving the needs of her parents-in-law who shelter her in the meantime in exchange for her good-natured labor. It’s not that they are mean-spirited; Mustafa is their only son, and with him away and their daughter married off and caring for an infant of her own, they are alone. Despite enlisting her work of all kinds, they are actually trying to help Meryem, whose own dad, a childhood friend of Süleyman, her new father-in-law, passed away without properly placing her with a spouse; so Süleyman kindly arranged the marriage to look after the unassumingly beautiful Meryem.

Atalay Taşdiken’s recent film, Meryem, is neither magical nor mythical; nonetheless it feels like a modern-day fable about women, men, and the snags in old village life that have yet to be satisfactorily unraveled. As Turkey’s heartland makes the transition from time-honored traditions to new social mores for a modern agricultural economy, its women, young and old alike, pay the price of change that its surviving patriarchal structure would just as soon forego.

Writer/director Taşdiken parlays his keen perspective on relevant issues into a filmic “village patois,” a cinematic idiom that syncretizes veritable local color and dreams. While persuasively portraying Meryem’s point of view, he also does justice to the predicaments of two other young men beside the notably absent husband, Mustafa. Both of these males are somewhat off-kilter.

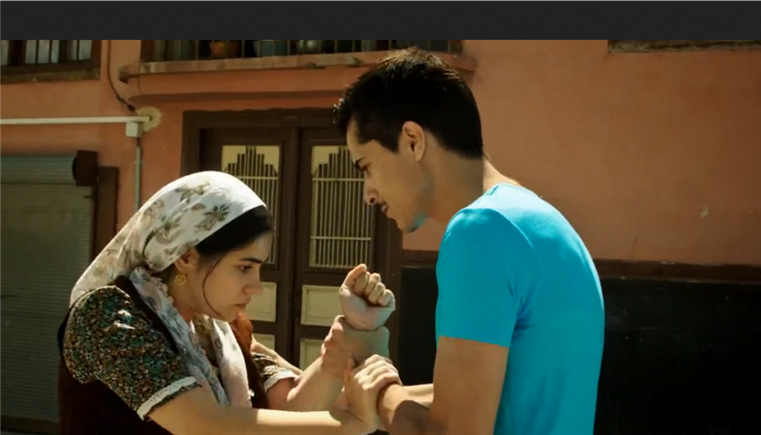

One, Murat, is a recent army veteran who is all-too-present in Meryem’s daily life because he fell in love with her just before he was called up to military duty. He pursues her adamantly now, and worse, in a kind of feverish rage, perhaps owing to the psychological imbalance with which active combat has left him. Shell-shocked, he suffers déjà vu and hallucinations, and he follows her on the village streets consumed with desire, surely in hopes of the calm her affections would bring him. His dialogue is sparse, better spoken through the songs he commissions at night when he can’t sleep: an old friend, serving as a cross between a minstrel and a griot, performs for him soulfully by the lake, playing melancholy ballads to soothe him.

The other young man drawn to Meryem is a neighbor who is also at a loss, owing to an impaired development that leaves him equally inarticulate. Yet she is impressively sensitive to him; so, as keenly alert as he is to Meryem’s vulnerability in light of her neglectful husband, her flaming would-be suitor, and the village gossip, this shy neighbor is her best defense. Tacit as he is, the film makes of him a uniquely effective, heartbreakingly sympathetic whistle-blower.

Meryem pines for a husband she doesn’t even know, longs for a life she has yet to discover, and mostly struggles to find a way to please everyone as a faithful and obedient member of the family and community, but ultimately she vents to her own mother, who has only one angle on the situation: “Everything comes to she who waits; once married, there is no turning back.”

The tension mounts as Meryem performs her daily chores, including tending to a sweeping field of snow-white poppies along with the neighboring women. She faints under the glistening sun. Is she pregnant, with Mustafa — or worse, Murat? When Meryem reluctantly confesses to Süleyman the threat Murat poses for her, this father by proxy is forced to seek a solution. Yet rest assured, Taşdiken has no Hollywood maternal melodrama in mind. It’s disarming to see this blushing bride’s face turn to sad dismay when she finds Süleyman has sold his cows, the family’s only source of income, to forward the money to his son, urging Mustafa to rent a dwelling in Istanbul for himself and Meryem; nevertheless, “all the bulgur in Anatolia,” packed up nicely in muslin bags for Meryem to deliver to her new home as she arrives, won’t settle the issue. Perhaps the money her mother gave her that she nestled into her breast pocket, “in case of hard times,” will be more meaningful in a new day.

Atalay Taşdiken introduces us to the Turkish province of Konya with a native eye for documentary detail. Outside of the principal characters mentioned here, most other actors in the ensemble of village dwellers are local inhabitants, lay actors proudly participating in location shooting near Lake Beyşehir, the region’s largest sheet of water, a jewel in the ecology of fish, birds, reeds, and mountain springs beside ancient stone carvings of Hittite deities. Daily life and the divine meet at the horizon here, where the filmmaker has previously made the documentary, Even the Sun Is Reluctant to Leave, a short piece about the legendary sunsets. Strangely, Meryem follows in this vein by working as an ethnography of the region as much as it does as an allusion to the “Old Anatolian myths.”

We follow the everyday cycle of labor as Meryem milks the cows, strains the milk into yogurt, sells it at the open-air bazaar, and works in a noodle-making brigade with the other women as they shape and dry the dough in the sun. After she cooks and serves dinner to Süleyman, we go with Meryem to a “henna party,” a bridal shower for a neighbor, where with all the brilliant costumes and dancing, the fiancée at the center weeps. These scenes beg the question of the issues behind them: arranged marriages; labor for in-laws and the servitude of women; entrenchment in ancient traditions and superstitions; abandonment and infidelity on the part of husbands; town gossip, harassment, and coercion; a lack of education for women. In short, a wife is not worth the bargain without “doing her duty” for husband and children — nor, for that matter, is a man a “man” without doing his compulsory military duty. The conflicts these issues present are palpable in the film, written on the face of Meryem (Zeynep Çamcı in her film debut) differently from moment to moment, her eyes brimming or screaming with quiet emotion, her lips quivering into a hopeful smile or carefully turning down in dismay.

The documentary realism brings a bizarre pang of guilt, though, because the vivid floral dresses and kerchiefs, the multi-colored paint peeling from old wood and stone surfaces, the brilliance of poppies stretching over the vast

meadow all register as immensely vibrant, as if pulled from a magic carpet ride of “Tales by the Lake” and lensed with the images a grandmother would create in spinning a cautionary bedtime story for a modern little girl. The spellbinding widescreen cinematography by Feza Çaldıran intoxicates us with color and light. The ambiance is unforgettable.

The most strikingly memorable are the dazzling turquoise of the Beyşehir waters and the glowing white — of Meryem’s flowing dress by the lake, of the poppies she picks in the fields, of the milk from the cows, of the gulls that fill the sky as they fly off in formation just after she tosses a pebble into the lake in the film’s opening dream and the ripples of the water spread endlessly outward. For all Meryem’s naïve purity and innocence, the repercussions of Mustafa’s departure grow as the days pass. The images resonate later when, near the end of the film, Meryem drops a huge jar of pebbles into the water, one stone for each day of waiting for her beloved, and the jar doesn’t sink in this strange lake that defies gravity. The buoyancy is portentous of Meryem’s path, mobile and mutable as water. Where it flows, nobody knows, but what is clear is that the motif leads to a revision of the ancient “vanishing-god” myth of Telepenus in the environs of the lake.

Hittite mythology has it that Telepenus, son of the Storm God and the Sun Goddess, grew angry after a failed feast and fled, spelling disaster for the divine, human, and animal worlds alike, leaving them all hungry, thirsty, and sterile. The Storm God took off to look for Telepenus hill and dale; the Sun Godess sent out an eagle for a bird’s-eye search. When all failed, a bee was sent to sting him where he slept. Upon his return the gods appeased him with various offerings in a ceremony that was a model of Hittite ritual practice.

All this echoes the film’s trajectory in pinning down Mustafa for Meryem, right up to the “sting” of the phone call to him answered by his mistress. Yet the “ritual offerings” the family has sent — dried beans, homemade noodles, and bags of bulgur for Meryem to take to Mustafa in Istanbul — are left by the wayside as Meryem moves on, leaving both the mythology and her plight open to interpretation.

Meryem, Atalay Taşdiken’s second feature film (which he wrote, directed, and produced) may seem as magical as it is real, but it’s no far-fetched exoticism of Turkish village life. Taşdiken himself was born and raised in Beyşehir and came of age beside the lake. He opens his film with an on-screen dedication to a real “Meryem” he knew throughout his childhood:

“The most beautiful woman in the town, loved and sought by all, suddenly went away. I used to hear my mother and sister talking about her. And I always wondered what happened to her. I never really intended to explain this,” he told the audience on March 7th at the LATFF, “but reality, life, is crueler than the movies. She went to Istanbul to live for two years, came back, lived with her mother, and was married off to a much older man. She died at the age of 32, but in my film, I wanted to be more hopeful for women.” The real Meryem died of lung cancer, and the film includes a scene in which Meryem scolds her father for resuming his old habit of smoking.

Regarding his style, Taşdiken adds: “I have a strong visual

background. As in my first

feature, Mommo, I wanted to

incorporate dreams into this script. They’re very strong in Eastern storytelling. They mean a lot to people. And I wanted the color and light in my film

to match and enhance the story.” Shot in High-Definition digital

with the Arri camera in Cinemascope format, Meryem

is as divine to behold as any legend of old, while its storytelling is

as relevant and real as we need it to be in sharing life in the Anatolian

countryside today.

Writer-Director-Producer Atalay Taşdiken

Meryem

Director: Atalay Taşdiken; Producer: Atalay Taşdiken; Screenplay: Atalay Taşdiken; Cinematographer: Feza Çaldıran; Editor: Serhat Solmaz; Sound: Ferıt Karabına; Music: Youkı Yamamoto; Production Design: Nurdan Tavukçuoğlu; Costumes: Rabıa Durak.

Cast: Zeynep Çamcı, İsmael Hacioğlu, Mustafa Uzunyılmaz, İpek Bilgin, Mehmet Usta, Derviş Deniz, Serhat Özcan, Hande Üzelsancak, Gaffur Uzuner, Yeliz Akkaya.

Color, Arri HD widescreen, 100 min. In Turkish with English subtitles.