7-17-16

Maurice Pialat: Life at Eye Level

By Diane Sippl

Jacques Dutronc in Van Gogh, 1991

What I understand by realism goes beyond reality… (in Lumière) men and women are captured by a machine they’re unaware of, surrendering an instant of their lives, which is what every actor has been doing ever since… Did Lumière film reality? I don’t think so. Lumière is a more fantastic filmmaker than Méliès. The cinema transforms what is sordid into something marvelous, it makes the ordinary exceptional.

Maurice Pialat, Cahiers du cinema, October, 2000

On Satan’s Turf

Overwhelmed with fatigue and at a loss for his bearings in the dark of night, a humble priest crosses the meadows and woods on a mission, only to be confronted by a visit from Satan. Cloaked as a traveling horse dealer, the devil tests the priest’s faith by instilling in him the power to see straight through to the human soul. Is such a “gift” a blessing or a torment? Does divine grace lie in the priest’s vision, or is such insight a curse that detaches him further from his flock?

This faltering character is Father Donissan in Maurice Pialat’s 1987 Palm d’Or winner, Under the Sun of Satan, and he is played by Gerard Depardieu, who by then came to be regarded as an uncanny stand-in for Pialat himself — Pialat who had, also by then, been tested many times by his constituency and had been saved by nothing if not his piercing compassion for those we would forsake. How did he do it? That is, how did he himself manage to manipulate and appall his cast, crew, backers, and audience alike and come out the other side of writing, directing, acting, and producing in a state of grace?

“Madame Bovary — C’est moi,” Flaubert insisted. The novelist’s inscrutable, compulsive, desperately desiring heroine, confined to the countryside and its social margins but having tasted the material and sensual temptations of Rouen, was a portrait of Flaubert’s longing self without virtue, predictability, or alibi. Unabashedly self-willed while caught in the web of ancient patriarchy and budding capital, Madame inevitably sinned; what Flaubert did was to show us not that she was immoral but that she was real. This was enough to create a scandal on the pages of his book and in the conundrum of his rapidly changing world. But the pen, he could control.

Gerard Depardieu and Sandrine Bonnaire in Under the Sun of Satan, 1987

Naked Childhood

Maurice Pialat’s films are filled with the fear and awe he experienced in his own life — yet not only of people and their uncontrollable casting of inclusive and exclusive nets, but also of the cinema and its uncontainable relation to reality. Pialat struggled amply with his own psycho-social demons, but perhaps more so with the possibilities that cinema unleashed. If Flaubert, who said he detested realism, penned his dreamily fixated alter-ego in his book, Pialat painted his own ego in his films, whether he played the roles himself or wrote them together with his real-life romantic partners, often “ex-es,” and directed them to play themselves on the screen. Still others, lay actors, were directed to take up various aspects of Pialat’s life before the camera.

If we consider the camera’s objective point of view to be at “eye level” in Pialat’s hands, we might just as well make the pun, “I”-level, because the list of ways this auteur inculcated cinema as self-portraiture is virtually endless. Yes, he began his adulthood as a painter and then acted in the theatre and made documentaries for TV, but none of these is the source of his realism as much as, he himself would argue, a deep sense of emotional abandonment in his early years, as articulated in his first feature, Naked Childhood, in 1968.

This kind of early trauma can breed distrust, bad faith, envy in lieu of loyalty, self-loathing where there should be love. Pialat was neither the first director to take up these maladies nor the last to work through them via his scripts and his actors. If his temperament led him to pursue such feelings not as ailments that needed to be healed so much as a seedbed for creativity, his relentless mining of base and wretched behavior was as unsettling as his intuitive compassion was inimitable. Perhaps it was this last feat — finding a cinematic means of iterating a recognition of “soul mates” — that left his fans the most in the dust.

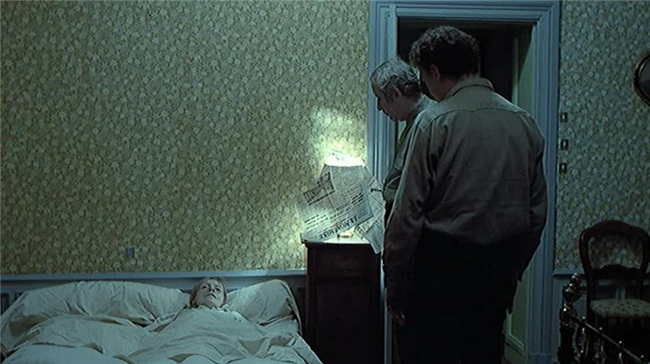

Monique Mélinand, Hubert Deschamps, and Philippe Léotard in The Mouth Agape, 1974

Some Kind of Realism

It takes but one encounter with this artist to learn what it feels like to be scrambling for a way “in” — into Pialat’s deep sensibility. For while we doubt, he knows; while we judge, he understands; and while we grimace, he accepts. To see at “eye-level” is the first step to showing life, but many wouldn’t perceive it that way. Pialat explores his characters candidly, but not through the mode of storytelling. Rather in flashes of disconcerting moments than in any narrative arc or even thread, he shows us their precarious relationships with each other: a bourgeois young lady meeting a ruffian at a dance in Loulou; a pregnant, “kept” woman taunting a self-flagellating country priest in Under the Sun of Satan; a daughter pursuing sexual conquests to spite her father in To Those We Love (À Nos Amours).

Nor do we get to look right into their eyes. The director rarely accommodates us with close-ups but rather with medium shots — fixing on Sandrine Bonnaire framed like a masthead on a boat or on Jacques Dutronc poised quietly on the grass but not complacent at all — or glorious wide shots of a lone figure traversing green terrain that should be idyllic but is really all but haunted.

Frustrating us with a lack of shot/reverse shot editing that unfolds and explains the scene, the filmmaker often drops us into it with little or no exposition and worse, hardly any resolution. We are in the moment — in Isabelle Huppert’s bed or at the bar with Gerard Depardieu — without knowing how we got there or why, with no establishing shot for the sequence, and no music to tell us the right way to feel. All’s a bit off-kilter: a son on the make while his mother’s on her deathbed; a newly ordained priest who asks to be secluded in a Trappist monastery; a financially insolvent Marquis fatally shot in his chateau. And yet all is so glaring in its physicality, its tactile incarnations of exhaust, despair, self-exile.

Prescient silences, structured absences, and long-take shot-sequences (on average, 9 minutes) that end with unexpected cuts can aggravate the viewer every bit as much as unwarranted cruelty or even just unmotivated actions — OR — they can stimulate speculation, spectatorship of the most active, passionate kind. Not to know but to wonder, not to control but to dream, not to recognize but to see, as if for the first time — is this not what cinema invites?

Isabelle Huppert and Gerard Depardieu in Loulou, 1980

An Impassioned Life: Pialat Paints Van Gogh

When the film begins, Van Gogh is unknown, he doesn't know he's Van Gogh, nor that he has only three months to live and 100 paintings to paint. One doesn't paint a hundred paintings in a state of depression. Van Gogh died having glimpsed happiness.

Maurice Pialat

Sartre reminded us that Flaubert, the so-called father of realism, “during his trip through the Orient, dreamed of writing of a mystic virgin, living in the Netherlands, consumed by dreams, a woman who would have been the symbol of Flaubert’s own cult of art.”

“My dear Maurice,” wrote Jean-Luc Godard, “your film is astonishing, totally astonishing, far beyond the cinematic horizon covered up until now by our wretched gaze.” That horizon on canvas was captured by the likes of Seurat, Monet, and Renoir; Pialat delivered it to the screen, but only as counterpoint — luscious foliage swaying in the breeze, ripples of sun-dappled water, but juxtaposed with a seeming lunatic who, fully dressed, runs right off the shore and the rowboat into the water. The film’s brothels and can-cans deliver us to Toulouse Lautrec, but only after Van Gogh parodies him outrageously at a picnic. Then days (or is it weeks or months) later, Pialat miraculously captures the delirium of dancing in a brothel for an exuberant sequence-shot of non-stop merrymaking with the whole ensemble headed straight for the camera. The gaze turns on us. If the Impressionists made a science of reality, Van Gogh was its alchemist: they mimicked what they saw; he transformed it.

And like the detached but robustly free Van Gogh — “prickly maverick” whose world was at a tilt — Pialat pursued his projects. A counter-realist by convention and an ultra-realist by impact, perplexing, alienating, never ingratiating but surprisingly rewarding, he inspired filmmakers and movie goers for generations to come.

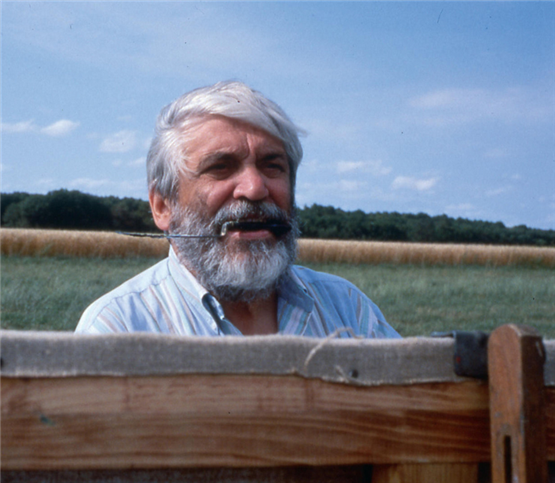

Writer, director, actor Maurice Pialat

Love Exists: Maurice Pialat Retrospective

UCLA Film and Television Archive

Billy Wilder Theater, Hammer Museum, Westwood

July 22-August 6, 2016

Naked Childhood, 1968

Graduate First, 1978

We Won't Grow Old Together, 1972

The Mouth Agape, 1974

Loulou, 1980

À Nos Amours, 1983

Under the Sun of Satan, 1987

Van Gogh, 1991

Maurice Pilat, Love Exists, 2007, by Anne-Marie Faux, Jean-Pierre Devisers