1-9-11

Mamma Gógó Looks Back:

The Ghostly Tales of Friðrik Þór Friðriksson

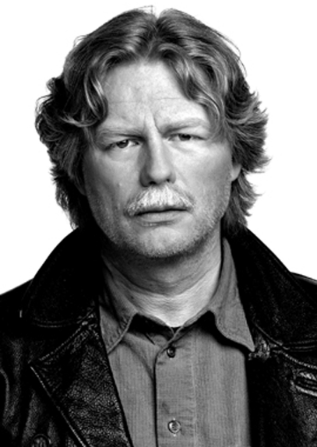

Friðrik Þór Friðriksson

One of the special delights of the Scandinavian

Film Festival Los Angeles (now in its 12th year, on Jan. 8, 9, 15,

and 16) is that the attendees get to meet and talk with many of the filmmakers and actors right in the theater lobby over Nordic drinks and “sauna” sausage

at the Writers Guild of America in Beverly Hills. Iceland’s Friðrik Þór

Friðriksson (Fridrik Thór Fridriksson) arrived this year along with his latest venture in writing, directing, and

producing — Mamma Gógó — making it at

least the fifth time one of his productions has been showcased in the festival.

His towering presence and husky voice seem strangely at odds with his quiet reserve and soft countenance. You shake his hand and feel he is at one remove from the world — or altogether too in-touch with it. While he looks like part Marlborough Man and part country preacher, he is really an erudite, globe-trotting, go-getter from Reykjavik who erupts with both tears and a belly-laugh in a single interview.

In his latest opus, drawn largely from his own life, this path-finding auteur makes inventive

use of several earlier Icelandic gems.

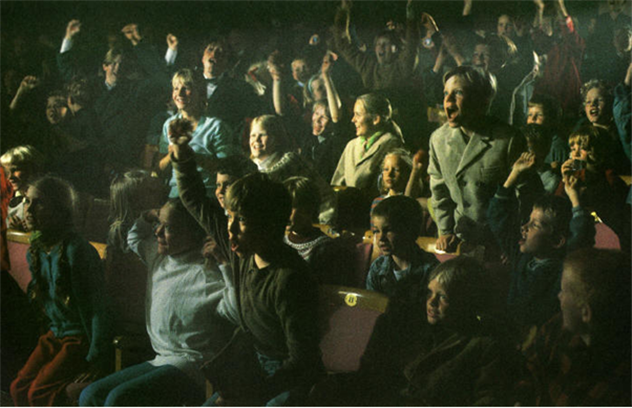

One is Girl Gógó (79 af stodinni, or Taxi 79), based on Indriði Guðmundur

Þorsteinsson's novel of the same

title. The film was enormously popular and also

controversial in 1962 when it was released.

Seen by 63,000 people in Iceland,

then about one-third of the country’s population, it was restored by The

Icelandic Film Archive in 1995. Friðrik Þór

Friðriksson also includes scenes from his own earlier, quasi-autobiographical

works, Children of Nature (1991),

which won him an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film, and Movie Days (1994) — both co-scripted

with his longtime best friend, Einar Már Guðmundsson — along with a brief clip from

Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush in

which the actor begins to eat his shoe.

Mamma Gógó

While writing, directing, and producing ten of his own films in twenty years, Friðrik Þór Friðriksson also managed to produce another thirty films with others at home and abroad through his own company, The Icelandic Film Corporation, putting his country solidly on the map of world cinema. But over the last decade Iceland’s economy collapsed, and his company fell into serious jeopardy. Around the same time, his mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. With creditors hounding him on one side and his mother slipping away into her own world on the other side, he decided to look with a certain lightness at the grave realities of his life. Defying the logic of space and time, these events became Mamma Gógó.

In a sense, Friðrik Þór Friðriksson is a “funny” kind of guy, but in the most unexpected ways. Certainly there is nothing funny about mental illness, which, as he shows us in film after film, can take hold of a person at any time from early childhood to late adulthood. Yet Friðrik Þór Friðriksson offers an oddly oblique perspective on these aspects of life. Is he guided by a certain slant of light pouring down from the Arctic circle? An extra sensory perception emitted from the land’s beds of lava rock?

His earthy humor anchored Angels

of the Universe (2000), his adaptation of Einar Már Guðmundsson’s sobering novel

that presents one suicide after another.

I’ve never seen a more sensitive, accurate, or imaginatively articulate depiction of

schizophrenia.

Not long thereafter, Friðrik Þór

Friðriksson turned right around and tackled autism in A Mother’s Courage (2009), a documentary lauded

for its spectacular visuals and enormous heart.

In Mamma Gógó (2010) it’s

Alzheimer’s, all tangled up with filmmaking, financial woes, and the treasures

of Iceland’s artistic culture.

These are heavy themes, but laughter lurks around every corner. Look at titles like Cold Fever, Devil’s Island, Niceland — and Mamma Gógó to boot — and know that you are walking hand-in-hand with ghosts, but that you have Friðrik Þór Friðriksson to shepherd you soulfully across their turf.

Angels of the Universe

A Mother's Courage: Talking Back to Autism

Mamma Gógó

Movie Days

An Elegy to My Mother

I’m often asked whether it is difficult emotionally to use elements from my own life in a film. But I have used my life as an inspiration before, namely in Movie Days, which was based on my childhood in Reykjavik back in the 60s. You have the feeling that at least you know your life well and there is some truth in it that shines through in a film that the audience can recognize.

Diane Sippl Well Mamma Gógó tells me a lot about who you are; in fact, I see the same artist — and the same person — behind every one of your films. Your thumbprint is there every time. But now for a different question: Many refer to you as the ‘Godfather of Icelandic Cinema’ for bringing so many people and resources together to make films that put Icelandic life and culture on the screen. What are your reactions to being considered a kind of founder or leader of a national cinema? What does it mean — what comes with it, and how does it work?

Friðrik Þór Friðriksson Maybe I once played such a role, but these times are over now. I don’t produce as much as I used to.

DS Except that you’ve produced a lot — some fifty films…

FTF Yea, yea, I have something to do with the most important films made in Iceland, in one way or another — working as a co-producer, or launching the projects. But now I take on very few projects. Since the economic collapse, the government cut down the subsidy by 35 percent, so you see very few films coming out of Iceland. It takes about two years to finance a feature.

People still come to me with scripts, and ask me for help, and sometimes I give them to other producers. I try to concentrate on my own films now more than I used to. So I will try to produce maybe two or three films a year, not more, mostly because the situation in Iceland is not so good at the moment.

A Mother's Courage: Talking Back to Autism

DS Both your film and our talk involve looking back in so many ways: at other works of Icelandic cinema, at other artists, at your own career, your family, your own life. When you put Mamma Gógó together, did it just evolve that way?

FTF Yea, well this project was always going

to happen. I didn’t know if I was going

to make it after two years, five years, or ten years, but I was definitely going to make this film before leaving this

earth, because it was so clear in my mind.

Once I see a film in my mind, I get a pain, so filmmaking for me is a

painkiller — it’s like I have to get rid of the film, get it out of my head.

DS When did you get the idea for making Mamma Gógó? Did you start writing it when your mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s?

FTF No, I made a documentary film that played on HBO last April, called A Mother’s Courage, about an autistic boy, and there are so many things people with Alzheimer’s have taken from this movie. I worked three-and-a-half years on this documentary. Kate Winslet narrated it.

The idea for Mamma Gógó came about five years ago because I thought it was ironic that the guy who made Children of Nature (1991) was suddenly in the same situation again with the characters, but in his own real life. So I connected the stories from my real life for Mamma Gógó.

Aud How long did it take to make Mamma Gógó?

FTF Oh, it’s just like a child — nine months.

DS Central to the themes of Mamma Gógó are themes and images from Children of Nature — in fact, the film itself. What got you making Children of Nature in the first place?

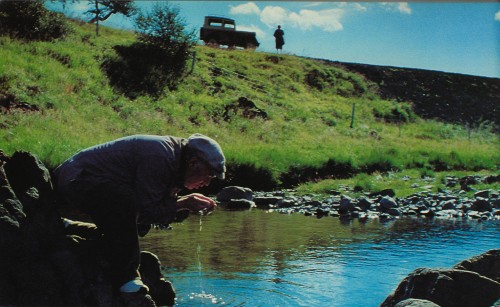

FTF Children of Nature is, well, like a gravestone for my father. Mamma Gógó is a gravestone for my mother. I used to work at this — I made gravestones for ten years. My father was about sixty years old in the film. He was born in 1896, so he was 94 in real life. In Children of Nature I was very curious about things he did before he died, because he did all kinds of strange things, the same things the man does in Children of Nature. So it was my experience with him before he died, and this was my marker.

DS What were the approach and the premise for Children of Nature? And can you tell me something more about your father? How did he influence you?

FTF Well he was a farmer in the north of Iceland on the farm where I shot Mamma Gógó. The beginning of Children of Nature and half of Movie Days were also shot there. My film, Falcons, with Keith Carradine, was also shot there.

It’s very dear to me, this place. My father died at age 76, when I was just a young man. He quit farming at 37. I mixed this up a bit, but this is where the idea came from. I made myself 10 years old, the age I was when I was sent from Reykjavik to this farm. So I compressed my life, but I used scenes that I really lived through.

In Children of Nature are all kinds of scenes that I experienced with old people, not only my father but also two old black guys I took care of in Reykjavik. One of them happened to be my father’s best friend. So I take everything from my own past like everybody else. It’s just like when you’re listening to a radio play or listening to a story — things just come to mind and then you put them together, and suddenly you have a film.

Children of Nature

DS What do you mean when you say that your father did strange things? He was out of touch, or creative, or what?

FTF No, for example there were these lava stones, so he walked barefoot on these, on the land he loved, and this is a scene in Children of Nature.

DS I know in the clip you used in Mamma Gógó, someone is carrying a dead dog.

FTF It’s the opening sequence of Children of Nature.

DS And then we see him bury it. So this just introduces the motif of death? How did you decide to use this clip?

FTF Well it doesn’t matter what I used, really. I could have used the end. In fact, I used the end, too. The irony is that the guy (me) who made the film about people going into old people’s homes has to deal with the same subject as his (my) characters in the film — that’s the idea.

DS What has happened with the genetic research and with the lab you refer to in Mamma Gógó as ‘Decode’?

FTF Well they were the first Icelandic company to go to the NASDAQ and the only Icelandic company to be on the NASDAQ, and they’re not doing so well. But I just met the guys recently, and they’re concentrating on applying their current research to schizophrenia, so the company is doing quite okay even though they’re not as big as they used to be.

Angels of the Universe

DS Now, maybe you think you’ve answered this, but it will never be answered enough for me. How difficult is it to write about your own life? Because I know I was intrigued when I interviewed you about Angels of the Universe that you said you knew the author of the novel so well. You grew up together?

FTF Yes, he’s been my best friend since I was nine years old.

DS And also his brother, Pálmi Örn Guðmundsson, named Páll as the main character in the novel and the film?

FTF Yes, of course. That’s why my son was playing his brother, the young brother he hits (i.e. — the author, Einar Már Guðmundsson, who would grow up to write the novel, Angels of the Universe about Pálmi and then adapt it to the screen).

I think Angels of the Universe was difficult for me because my friend’s parents were alive, and they were good friends of mine, of course. So I had to think about it, because when the novel came out they had to go through grieving a second time, and then for the third time, of course in a much stronger way, when they saw the film. But with my own mother or my father, it’s just another gravestone for me to make. I know they will be happy with it, so…

DS So what does it mean when you say ‘it’s another gravestone’? I think a gravestone is different for you than for a lot of other people.

FTF Well that’s why you make a gravestone — to keep the memory alive.

A scene with Kristbjörg Kjeld in Girl Gógó used in Mamma Gógó

Movie Days, or “Thank You for the Music”

Being an old cinephile, I have always made references to

film history and quoted other filmmakers in my works. I’m proud to be a part of film history and

like to say ‘thank you for the music.’ As

Stanley Kubrick

puts it, ‘A film is — or should be — more like music than like fiction. It should be a progression of moods and

feelings. The theme, what’s behind the

emotion, the meaning, all that comes later.’

DS Can you tell me a little bit about your actress for Mamma Gógó, and who she is in Icelandic cinema, and how you used her in your film?

FTF The black-and-white flashback at the end of my film is of Kristbjörg Kjeld, the same actress who plays the lead in Mamma Gógó, as the title character in a film from 1962 called Girl Gógó (or 79 af stodinni); and also the actor, Gunnar Eyjólfsson, who plays the father in my film, played her lover in that film, as you see in the flashbacks.

My mother, who is now 96, was starting to get Alzheimer’s about ten years ago, so I was really waiting for Kristbjörg Kjeld to grow older so that she could portray her in this role, because I couldn’t imagine anyone else who could do it. Kristbjörg Kjeld has acted in over twenty feature films during her career that spans more than fifty years, but she has achieved even more in theatre than in cinema, and she’s a good friend of mine.

Kristbjörg Kjeld in Mamma Gógó

DS Can you tell me about Girl Gógó? When I read the credits at the end of your

film, Mamma Gógó, I was fascinated

that you were using clips from this 1960s film.

Of course the lead actress is the same in both works, but how did you

decide to juxtapose the color and black-and-white footage in your own film and

scenes from that film? What does Girl Gógó mean to you?

FTF Well, 79

af stöðinni (aka Girl Gógó) was

one of the first Icelandic films. It’s

by a Danish director, Eric Balling, but it was one of the first films shot in

Icelandic with sound. It’s based on an

Icelandic story, a novel by Indridi G. Thorsteinsson in our own language, so it

meant a lot to me. One of the reasons I

used Girl Gógó was that the

character’s name was also Gógó, the name I gave my mother in my film, which is

her nickname in real life (from Gudridur), so there were too many coincidences

— you have to take it as a sign.

Gunnar Eyjólfsson in Girl Gógó, in a scene from Mamma Gógó

DS Kristbjörg Kjeld is so beautiful in it, and the male romantic lead, Gunnar Eyjólfsson, handsome as well, yet it’s the relationship between them — lovers when we see them in black and white (in the footage from Girl Gógó) and married when we see them in color (in the Mamma Gógó story) — that literally moved me to tears. It happened to everyone around me as well. But it started earlier, with the director character talking to his mother face-to-face, telling her how much she means to him. That simple act is very moving, very penetrating. And then it’s quite something to see the scenes from Girl Gógó as part and parcel of your film. To pair the two sets of images lets the audience put the two films — which are really one life — together. It creates an effect at once dignifying and reassuring, with regard to your actress, your character, your own mother, and any mother.

I guess I’m wondering if Icelandic people find the whole experience even more particularly overwhelming, because of their familiarity with the novel, the film, and the actress.

FTF Even though both the novel and the film were quite popular when they came out, most of the new generation has not seen Girl Gógó.

DS Really? Is there a way in Iceland, a cinématheque, where they can get the chance?

FTF They can buy this film. It’s easy.

DS But it’s the universal problem of young people losing their history, their culture?

FTF No, also losing the taste for black and white films.

DS But it’s so beautiful.

A scene with Kristbjörg Kjeld in Girl Gógó used in Mamma Gógó

DS Mamma Gógó makes so many references to Icelandic arts. Beyond using footage from other films, you mention names of particular poets and painters, and you pay special attention to music. How important it is for you to either preserve the culture for Icelandic people or to put it out to the world as an emblem of the creativity you know?

FTF Ya, it’s a mixture of both. It’s something I was brought up with, that really made me what I am, so I think other people would like it as well and appreciate it as much as I do. Still, it’s more in the countryside of Iceland. People start to sing when they come together. And it happens that where I come from, in the North, there are great singers there — really beautiful singers. It’s a ‘natural touch’ with art, and at a very high level, I would say, because these people are farmers and amateurs, not singers by profession. And that’s what I like about it — it comes so naturally. You don’t need to go far for this culture, because it’s still very much alive.

DS In the care home where the mother is staying at the end of Mamma Gógó, the camera pans really slowly across a number of faces of people who live there and we hear a very eerie kind of music. The camera rests on the person playing the instrument — what is that instrument?

FTF It’s not a musical instrument; it’s a tool. It’s a saw.

DS So this is his own creation?

FTF No, some people play with a saw. He was extremely good.

Hilmir Snær Guðnason as Mamma Gógó's son, the Director

DS You use a quote in the film from Oscar Wilde — there’s dialogue back and forth about who discovered America.

FTF He said that the Icelandic people belong to the most intelligent nation on earth, because they discovered America and decided to lose it.

DS It leads to some other lines in the film that maybe have more meaning for you and people from Iceland than they do for American audiences. One line with which I whole-heartedly agree is a reference to Hollywood…

FTF “Hollywood is all about killing time and stuffing people with junk so they won’t be hungry.”

DS Now the irony is that not only are you positioned for an Academy Awards nomination today as we speak, but also in your own script for Mamma Gógó, your character is hoping for one, so are you counting on the audience to piece together the irony of this?

FTF Ya, if this is irony. You know, I just put it out there…

DS Well your Children of Nature did win the nomination, but for me there’s a gap that is difficult to bridge. Sometimes I find it hard to laugh at the Academy and what it means in world cinema, the way it dominates the scene and the distribution with its own product. Sometimes I feel I’m fighting the Academy to be able to see a film you would make. You can think of it that way.

FTF Ya, well, and also, if you look at my story, without my nomination from the Academy, maybe I would have made three or four films in my life, but now I have made fifty, so look what the Academy has given me by putting a focus on Iceland — a whole new age of film in my country, so that’s beautiful.

DS It’s a central paradox in this film, don't you think?

FTF Nah, it’s just humor. You know my Movie

Days and Devil’s

Island were both entries for an Oscar.

Devil's Island

Some people here said that there was an anti-American feeling in them, but they were absolutely not taken in that sense around the world. It’s only here. And I doubt people would see it this way today, because since Obama came to power, so much has changed.

DS Well Movie Days is history — it’s film history, and it’s your history. It’s also American history.

FTF It’s linked to American history in the sense that it was my answer to Woody Allen’s Radio Days.

Mamma Gógó

Ghost Stories: Poetry Sometimes Writes Itself

Often people see symbolism in my work. I say that this is purely accidental, I’m not always aware of what I’m doing. But many things in life happen like that: purely by accident. Poetry sometimes writes itself.

DS You make one of the most beautiful comments through your main actor, Hilmir Snær Guðnason, who plays the filmmaker in Mamma Gógó. He says, ‘Funerals are now the only place where people can be at peace and think beautiful thoughts about others.’ It’s a very strange comment to hear in general conversation. I’ve never heard anybody with this perspective. How does a line like that end up in your dialogue?

FTF Well I said this because I started a new trend. When I was beginning to make films, the trend was road movies. So I said I wanted to set a new trend called ‘funeral films.’ And I made jokes about that.

DS Is this your signature, in a way?

FTF Ya, it’s a signature.

DS But it’s more than that.

FTF No, it’s a true thing.

DS Ya, but it’s deeper, because…

FTF When you think about it, you come from a stressful life, and a friend or relative dies, and then you have to sit there for more than one hour, and what do you do? You start to think about your own life first, and it brings some memory with the one you are burying, and then you start to think about your own life and what you have been doing with your own life, so it’s like a natural yoga. And the music is great.

Ingvar Eggert Sigurðsson in Angels of the Universe

DS So like your mother character, you would also crash funerals, if you felt like it? I’m not saying you have; I’m saying you might.

FTF Well it’s in my films. Some of my characters have been funeral collectors. They go, like in Cold Fever.

DS I think it’s even more than that. When I interviewed your two actors in Angels of the Universe, Baltasar Kormákur and Ingvar Eggert Sigurðsson, they told me something funny about you, and it has never left my mind. They said you believe in ghosts, and I said, ‘Come on, I know his films have these motifs and even this style from time to time of people popping up onto the screen, but what are you saying?’ And they said, ‘No — he really believes in ghosts.’ Now what’s your reaction to that?

FTF Well, it’s so natural. I’ve sensed it so many times. Supernatural things are so natural to me, because I believe that dimension takes place in reality, and you know, I have experienced so many ghosts in life.

DS How? What do you mean, you ‘have experienced ghosts’?

FTF Ghosts are all over, everywhere, not only in Iceland. You can say elves probably are special, and sea monsters in Iceland — that’s so easy. You are crazy if you have seen a monster or a UFO, but ghosts, and elves — they are something that’s very natural.

Cold Fever

DS What’s an ‘elf’ to you?

FTF An elf is just a creature that doesn’t appear in our dimension. They exist. I can tell you a good elf story. I’m making a documentary to change the history of Iceland, because we believe that we were discovered by Vikings in the 8th century, but I know this is wrong. So I’m making a film about ruins that my friend and I found. We’re working on this documentary with an old man who agrees with us, and he’s been holding this theory for ages but no one believes him.

So I went there finally, two years ago, to study this site, and was driving along the way, when this old man called and said, ‘Friðrik, you’re so lucky, because the elves love you. I think it’s because of Cold Fever that they love you so much. So they baked a cake for you — there’s a cake from the elves waiting in the fridge.’

And I thought it was kind of a joke, and after we were through shooting for the day, he invited us for a coffee, and I forgot to ask about this cake. And I completely forgot, because I was so anxious to work on the subject we were filming that not even a cake from elves could mean something to me. So we headed back to town.

And then we were shooting again and the guy said, ‘I’m very sorry about the elves’ cake. They’re very happy that you’re coming here, but they were very angry with me when I called you and said they had baked a cake for you, so they took the cake away. But they told me that they still like you, so don’t worry about that, and there are very few people they have made a beautiful cake for. I saw this cake, and I can prove that, so you have to believe it. They were very angry with me, so I promised them never to interfere with what they’re doing…’

They don’t want to be recognized. He should have just given me the cake, and not said that it was from the elves.

DS Because this is the way elves work. So he broke the code.

FTF Ya, without knowing it.

DS So elves are good.

FTF No, they can be mean, also. These guys were very mean to him when they came…

Kristbjörg Kjeld and Gunnar Eyjólfsson in Mamma Gógó

DS …And took it back. Along the lines of ‘natural’ and ‘supernatural’, or whatever way you want to look at it — I want to know about the pop-ups that appear in Mamma Gógó, some people would say magically, as they do in Angels of the Universe, and maybe as they do in other films of yours. You use them a little bit differently each time, technically and artistically. Was it any easier to achieve the effect you wanted in making Mamma Gógó in 2009 than it was when you made, say, Angels of the Universe in 2000, in terms of the techniques available to you?

FTF Ya, it was.

DS Is it simply digital effects this time?

FTF Ya, I shot this film on the RED camera, so it makes all the effects very easy.

DS Sometimes the father dissolves in, and at the end, at the cemetery, the images remain superimposed for some time. Why is it that you do it? I’m not so concerned about the technique, but how this becomes your way of visualizing your work.

FTF It’s just part of my life, so I have to visualize what I am seeing and just make it honest. You know, I’m not doing big effects — they’re very simple and very low-key. It’s just like it happens in reality.

DS So it doesn’t feel magical to you. It conveys your own real experience.

FTF Yes. When you see a ghost it doesn’t come with Dolby Surround Sound.

The Ubiquitous Red Car

DS Now I keep wanting to ask you, in Mamma Gógó, when the red car moves along the horizon and drops her at the cemetery where she first plants the flowers, it looks like there is no driver. Is this true, or did I see it wrong?

FTF No, it’s true.

DS It’s a ghost car, right?

FTF Ya, because we are looking at it. She doesn’t see it that way. She sees him.

DS It’s an ingenious touch. ‘Magical’ in my language, I guess. What kind of character was Girl Gógó? Was she like your mother, or just in name, a coincidence?

FTF Maybe, but you know she was having an affair with an American soldier from the NATO base in the film. This story has nothing to do with it, but in reality my mother was with a British soldier before the Americans took over, because Iceland was occupied by the Brits first, in 1940. And they say, ‘that was the first involvement with the Americans,’ because the Brits never would have occupied us without Roosevelt being aware of it. So that was just the first stand, through the Second World War. Roosevelt knew what was coming. Churchill came to Iceland, and they occupied Iceland on the 8th of May in 1940, and already then the Americans helped — they took a stand, I guess. But you have to ask historians.

Look! See this — ? Ha! Ha, ha, ha! (With roaring laughter, he nods in the direction of the street, outside the huge window behind me, as a vintage red-and-white car cruises slowly down Doheny Drive in Beverly Hills looking incredibly like the car in his film in Iceland that we have just discussed.)

DS Oh, my gosh! It’s you — you bring this, I know. Everywhere around you there are elves and ghosts and omens — you had a black cat, at the end of your film, walk across the path of your mother and father, but they were already down the path. The cat crossed after they left, not in front of them.

FTF Yea, yea.

DS Because you know, black cats … so why was the cat in the film? For that reason?

FTF No, it just came.

DS Oh, my God — no, no, don’t tell me that. So you do this. You walk in the world, and then these things happen to you, right?

FTF Well, Kubrick said, always use your mistakes, because that creates some kind of mystery.

DS But that wasn’t a mistake. Somebody sent that cat because you were there.

FTF Ya, ya — but there was no animal trainer.

DS And somebody timed that cat to come after the couple was free of it.

FTF Yea. Yea.

DS Just like someone sent that red car on the road now — somebody sent it. (He laughs.) I don’t know who, but maybe you know…

Mamma Gógó

Director: Friðrik Þór Friðriksson; Producers: Friðrik Þór Friðriksson, Gudrún Edda Thórhannesdóttir; Screenplay: Friðrik Þór Friðriksson; Cinematography: Ari Kristinsson; Editing: Anders Refn, Sigvaldi J. Kárason, Tomas Potocny; Production Design: Árni Páll Jóhannsson; Costumes: Helga I. Stefánsdóttir; Music: Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson.

Cast: Kristbjörg Kjeld, Hilmir Snær Guðnason, Gunnar Eyjólfsson, Margrét Vilhjálmsdóttir, Inga María Valdimarsdóttir, Ólafía Hrönn Jónsdóttir

Color, 35mm and DCP, 88

minutes. In Icelandic with English subtitles.