2-2-20

“Magic, Creatures, and Legends: A Journey into Nordic Folklore”

By Diane Sippl

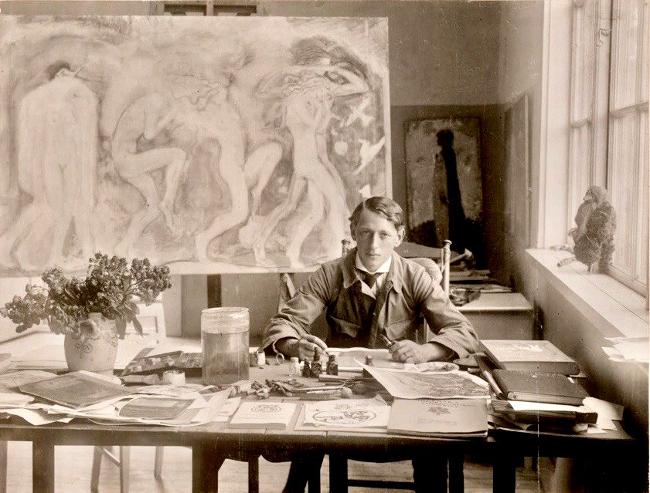

Picture a sandy-haired boy who steals away to the forest, bending an ear for the “little people” behind the rocks and trees. He doodles his way through school, sketching his teachers with exaggerated features, only to land at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts. There a rare beauty with long golden tresses captures his heart. Together they draw and paint; he makes her his model and muse, his “Fairy Princess.” He writes to her from the far North, where he’s been sent to study a strange way of life, that of nomads who raise reindeer. The Sami are as shy as he is, so he mostly takes notes and photos, sketching their tools and clothes, which find their way onto the bodies of gnomes and trolls he paints with a vision all his own. He marries his muse and they journey South, traveling back in time through art. But their Renaissance days end with a murder next-door, so they leave Rome to return home. This time it’s a steamer, loaded with cargo, sewing machines and iron stoves, that takes them down, down, deep into a lake where they will never see the sun again. It is said in the news that the forest spirits, in pursuit of the artist, sank the ship.

On February 7-8, 2020, the 21st Nordic Spirit Symposium at the Cal Lutheran Campus, Thousand Oaks will host prominent scholars in the field who will bring the latest insights into “Magic, Creatures, and Legends” through story analysis, painting, and song: how to recognize these supernatural creatures, what to do when one encounters them, how to understand the thin veil between reality and the ghostly, and what spells to use when one hears a twig crack in the woods or glimpses a shadow among the rocks. As presented by the Scandinavian American Cultural and Historical Foundation and California Lutheran University, the symposium will combine lectures, music, food, performance, and conversation to enhance the pleasure of learning.

From among the eight cross-cultural and interdisciplinary presentations over the two days, this article will contextualize the work of a particular visual artist by focusing on the lecture, “The World of John Bauer” by Ernst F. Tonsing, Professor Emeritus of Religion and Greek at Cal Lutheran University. Fred Tonsing, as we know him, holds a Master’s degree in Religious Studies and a PhD in Early Christian Literature and Art from the University of California, Santa Barbara. His travels as a scholar to the Middle East, Europe, and Central and South America have led to his publication of 40 books on history and Scandinavian topics. The following interview paves the way for appreciating “one of Scandinavia’s greatest illustrators of folk tales.”

KINOCaviar What are the differences among modes of expression such as myth, legend, saga, folk tale, fairy tale, and ghost story? I’m sure they overlap, but what’s the core element of each—even if there might be one example that includes them all?

Fred Tonsing They all exist in the same realm, but there are distinctions. Myth is more public and quite often has to do with the high gods and goddesses like Thor or Odin and Freja. The myths were told by roving minstrels who went from village to village or house to house in Scandinavia, and they would spend night after long, dark night sharing them, usually in poetic form, in song.

But alongside of those were the folk traditions. The folk tales and fairy tales are related. Fairy tales have to do with supernatural beings; they’re never true. Folk tales, on the other hand, quite often have roots in places, things, or persons. Fairy tales deal with fairies and all sorts of beings that inhabited the world of people before the industrial age, whereas folk tales might deal with a certain rock, a large rock, that’s in a churchyard in central Sweden.

“Now giants had inhabited the mountains for millennia. They did not at all like these Christians coming in and building churches. Such newcomers built a tower and put a bell in it and started ringing it, which made a giant furious, so he told his daughter, ‘Go up there on that mountain. Take your apron as a sling and shoot this rock at the church to destroy it.’ She missed, and the bells kept ringing, and the giants never returned.” That’s a folk tale that has to do with a specific item, in this case a rock—a real rock—I’ve seen it. It stimulated something that actually happened—a real object, a real event.

As for ghost stories, people were always very wary of ghosts, the dead, and there were various kinds. Quite often in old Scandinavia they were afraid the ghosts would return or come and do some evil in the house, but a ghost could only come in through the same door where it left, so people would break a hole in the wall of a house and take the corpse out through there to bury it; then so that the ghost couldn’t come in, they’d fill up the wall. If people had been evil in life or if they had died a bad death, their ghosts were malevolent, but if they had died a good death, a peaceful death, then they would not be. So there were two kinds of ghosts, but even at that, people were not sure that they wanted them to come back. So quite often, the place to bury the dead was at a crossroads; for example, if the life had ended as a suicide, which would have been a bad death, then when the ghost arose, it wouldn’t know which way to go….

I’m not a folklorist, but I’d say a legend has to do with the stories of a place, a person, or an event, and they are more developed, sometimes literarily, but through telling and retelling. Some will migrate, so a legend will be told about a particular person in one place, but then the same story will be told about another person in another place. What’s interesting is that many of the legends go back two millennia; we know because some have popped up among the Roman writers. Some of the legends moved down into Germany.

KC Giants and ghosts are familiar enough, but what are trolls and tomtes and nisses?

FT Nisses are another type of being, quite often inhabiting waterfalls or rivers, like water nymphs. They’re men, usually, and they play a violin, but there are all kinds of stories, and sometimes nisses are women. Then there’s Hulda, the witch of the forest, who’d attract young men deep into the forest to do certain sexual things. There were mermaids. For instance, Hans Christian Andersen’s “Mermaid” is another story that’s pan-Scandinavian. And there are mermen, too. The forests and rivers and waters were filled with these little beings, some very nice and some not so nice.

There’s a story of some youths, boys and girls who liked to go out into the forest and dance, which they weren’t supposed to do. “They’d form a circle and sing and dance around, but they had no fiddler. One day a man appeared with a fiddle under his arm and a bow and he asked, ‘Well, shall I play for you?’ ‘Oh, please do!’ they said. So he started playing, and they danced to the beat, and he’d speed it up, and speed it up, and speed it up and speed it up ‘til they cried out, ‘Slow down, slow down!’ but he didn’t, he just kept speeding it up. They wore off their shoes. But then they wore off their feet, and their ankles, and legs, and bodies, until finally just their skulls were bouncing around on the ground, and they kept screaming. The local pastor heard the noise, and he went out to the forest and recognized this. He said, ‘Fiddler, stop and be gone!’ because he knew it was the devil. Somehow the children’s bodies were restored to them. They went back to the village. Never again did they go out to that forest glen to dance.” Now that’s an example of the stories that are told.

KC How do you know this tale?

FT It was passed down to me by my Swedish grandmother who lived with us for ten years. She was born here, in the U.S., but her husband was Swedish and her parents were Swedish. Occasionally you’d hear noises outside, and she’d say, “That’s a tomte.” She thought they were out there. Usually the tomten were little shoemakers, so in the winters you could hear them tap, tap, tapping on their shoes, banging the nails into the soles. Certain sourpusses would say, “No, that’s just the ice cracking on the lakes.” But my grandmother knew it was a tomte. And every Christmas you had to set out a bowl of milk or porridge on the step for that tomte, who had always lived on that same property—families could change, generations changed, but that tomte was always there guarding the place. You had to treat him nicely, because if you didn’t, the cows would stop giving milk, the sheep would stop giving lambs…. So you would place a little bit of porridge or milk out there on the porch and he’d be satisfied for the year. You made him happy.

KC I heard that if a character were endowed with magical powers, it could be a bad thing—the magic was a virtue, but it could be a punishing one.

FT Yes, it could be good or bad. For example, before the modern era, usually the pastor, who had been trained at a university, was the only one who could read and write, so he would act as the doctor for the parish, which covered many, many miles. Therefore, the pastors were thought to possess certain magical powers, but they used them for good. Others did not. The birthing of a child was very, very dangerous, so quite often, during the delivery, the midwife or her assistant would sing an appropriate song to make sure that the birth went well and there was no danger to the child. So those were “good” magical powers, as well.

KC I read a story last night—a Danish tale but maybe based on old Icelandic tales, who knows—told by Isak Dinesen, about a king who had lived in old times. In his chambers, the king was quite sad and introspective. His loneliness drove him out into nature to seek his “path.” He rode his horse through the forest to the water’s edge and visited an old thrall. What is a thrall?

FT A thrall would be a servant, but in earlier Viking days, a slave.

KC The thrall brought a fish to cook for the king, and when he gutted the fish, inside was a ring. “I’m honored here,” thought the king. But then a guest recognized the ring—the one from the hand of a princess as she’d floated in a boat upon that water. The ring had fallen to the water, to the fish, to the thrall, to the king. When he went out to return it to the princess, the king met his death. Such was the magic—not just that invested in trolls or monsters, but the magic itself—dangerous and bad.

FT Of an object, yes, especially a ring. Richard Wagner, of course, wrote the operas Der Ring des Nibelungen about this gold that was owned by the Rhinemaidens that Alberich, the evil dwarf, stole and then made into a ring. Then everyone who wore that ring was cursed until finally Wotan threw the ring back and the Rhinemaidens picked it up and put it with their treasures. Ring stories are really wonderful stories.

KC So is this an example of an “ur” form? Did it come up, really, in Germany, separately from any ring stories in Scandinavia? Or do you think it migrated?

FT Who knows? Well Denmark, of course, is the peninsula to Germany, so it’s Germanic, although the Danes don’t follow that, and they’re still angry that Germany took over Schleswig-Holstein, the northern Schleswig area near Hamburg, because that was Danish. My father’s family was partially from there. But yea, a lot of these stories do migrate, yet we don’t know how—through minstrels, or what have you. There are thousands of stories; anthologies of Scandinavian folk stories are 600, 700, 800 hundred pages long sometimes.

KC Let’s talk about the visual dissemination of Nordic tales. John Bauer’s illustrations in children’s books were published even long after his death in 1918, straight up through the 1950s. We’ve relied on his prolific body of work. Were those books part of a trend?

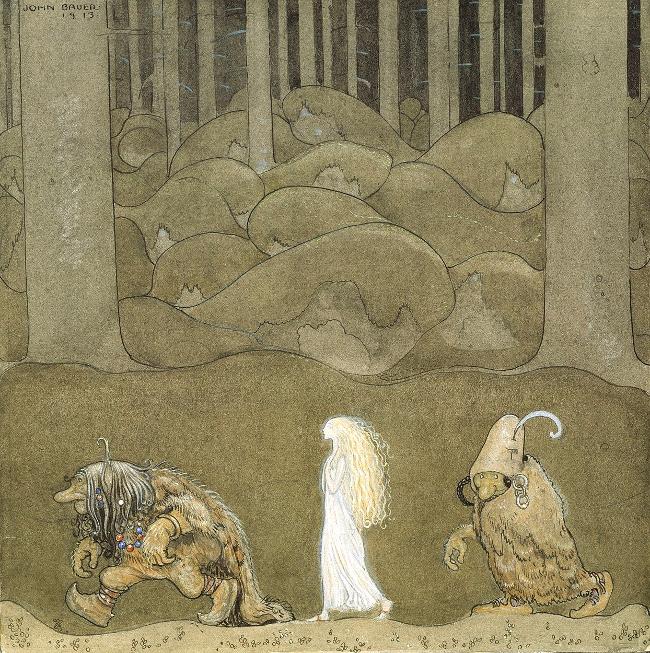

FT John Bauer never really went out of fashion. His illustrations for Among Gnomes and Trolls continued to be popular into the 1950s, but almost every book of folk stories and fairy tales from Scandinavia, right up to today, will have one or two or more of his pictures. He was not the only one to illustrate trolls and tomtes and nisses, and there are dozens and dozens of beings that inhabited the forests and lakes and rivers in Scandinavia, but he gave us the most memorable ones. So today when one thinks of, especially, a Swedish troll, John Bauer comes to mind. When one thinks of a little princess—John Bauer.

There have been other illustrators who have given us their images that are known world-wide. For example, Gustaf Tenggren, who lived after John Bauer’s time—certainly knew his works, and developed his own style—was invited to Hollywood. Gustaf Tenggren gave us the films Pinocchio and Dumbo but also Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs—straight from John Bauer’s little princess and the seven tomtes.

KC Did John Bauer interpret or visually embellish the tales that he painted? I guess these were based on common knowledge, but did he add any creative elements to the look of these characters?

FT He certainly did. The difficulty when you’re illustrating a children’s story, or any story (unless it’s cinema, where you can have a continuous series of pictures), is that you have to isolate the key event that typifies the whole story, so that you can read what happens before it and even maybe what will come in that one picture. And that’s difficult to do. But he was very good at taking just that one instant and illustrating it.

He loved picking up rocks and moss when he was a kid, and in Stockholm he’d go to the archeological museum where he could find the Viking artifacts that were just then being discovered, in the late 1800s and early 1900s. He would go to Skansen, a new outdoor museum in the late 19th century, for which Artur Hazelius, a scholar and folklorist, collected buildings as we would collect postage stamps; from all over Scandinavia, he brought them to a park he designed in Stockholm. Historic buildings from the 9th, 10th, and 11th centuries up through the 19th century were delivered to Skansen, and Bauer would go there and wander about, making notes. In his art, you would see quotations of these buildings.

KC What do you mean when you say historic buildings were “collected”?

FT He moved the whole bloomin’ building to the park—oh yes, the whole thing, furniture sometimes, even. He’d just buy it and move it. It’s a huge museum.

KC It must cover a vast land, to contain all these buildings.

FT Oh, yes—and it has a zoo, because he also liked animals. He gave the idea to other Scandinavian countries and other European countries to do the same, to preserve old buildings. This one is in Sweden. It’s a wonderful place. You spend all day there.

In Bauer’s paintings and pictures of trolls—well there’s a certain building from Blekinge or Dalarna—you see that building and say, “I know that building—it’s right there.” Or in his costumes of the trolls—a troll woman will wear a broach but then a chain hanging from it, and it should have another one, but the trolls are a little sloppy, so they let the chain go. Or the earrings, and the bracelets, are right out of the archeological museum where they were digging up Viking artifacts, so Bauer would combine them in the attire.

"One evening around midsummer, they went with Bianca Maria deep into the forest...

John Bauer, 1913, watercolor

KC So he exaggerated their length or their ornateness?

FT He exaggerated them or combined them in his pictures; there were all sorts of elements that he would quote.

KC So the elements might be real, but he elaborated them or extended them…

FT And combined them in unique ways, or simplified them, because sometimes these little sketches were half the size of this menu or half the size of your 8½ x 11-inch paper. They’re small.

KC Were there other sources of inspiration for his creativity?

FT Early in his career he was sent up to what was then known as Lapland to study the Sami people, so he lived with them a whole summer. When he painted water colors (and later oil paintings that he derived from those), he was to report to the government his impressions of the Sami. They wear a kind of a high hat. Well if you look at Bauer’s trolls, they have these high, domed hats, but John Bauer doesn’t just want to stick a hat on a troll—he puts a feather in it that comes up to decorate it, as a little bit of frivolousness.

KC Is that a kind of signature of John Bauer?

FT Yes, sticking the feather in the hat.

KC But the hat is recognizable as a Sami hat?

FT Yes, or the trolls carry a Sami knives, which are curved and inscribed with particular designs.

KC So he was sent to the far North as a kind of ethnographer? And then he recorded his findings visually for the government?

FT Yes.

KC And what did he think of the Sami people? Do you know?

FT He admired them, very much.

KC For

what?

FT For the lifestyle. You know he’d grown up in the forests of Southern Sweden, which are very dense and very dark, and he got up to the tundra, and there were these wide, open spaces with brilliant light from the sun, also reflected from the snow. He admired the Sami for how they were able not only to survive but even to thrive in such difficult circumstances. He admired their houses, their very colorful clothing, their pointed shoes, which are nice for walking in the snow, and their exquisite knitting, weaving. Their clothes were beautifully woven, just wonderful.

KC So they’re in the Arctic Circle, right?

FT They’re usually above the Arctic Circle, although some of the urban Sami come down to Stockholm or Oslo or other major southern cities.

KC But they’re not like the Inuit peoples of Greenland, Canada, and Alaska? Do they live in igloos?

FT The Sami peoples are somewhat related, but those who are reindeer herders usually live in skin tents or teepees that are constructed of wood slats with a skin door.

KC Even in the snow?

FT Even in the snow, oh yes.

KC Did Bauer know any Sami language?

FT He must have—I’m sure he learned much of it. He spent a year there.

KC And when people look at Bauer’s work, can they immediately recognize the Sami elements in the images?

FT Yes, but that’s not all. There’s the Italian Renaissance—he took part in the late years of the pre-Raphaelite movement, which responded to the details and complexity of history painting and the imitation of nature in the early Renaissance. But more than anything, he was part of Art Nouveau, in which you have these long, graceful lines with elegance. The tree roots in Bauer’s work intertwine in beautiful patterns. The princesses’ or the princes’ dress styles are medieval but they’re really Art Nouveau with long, sinuous lines. This is before Art Deco and kind of verging on it, but still Art Nouveau. It’s a period around 1912, before World War I, when there was a reaction against the classicism and the various forms of academic rigor in which you had to look very Greek or Roman.

KC Did John Bauer manage to move from very small work to very big work?

FT Well, yes. Toward the end of his life he felt a little constricted by doing just illustrations for children’s books. He really had grander aspirations, so he painted some large murals that covered a whole wall, one in particular of Freja, the mythological goddess of fertility. It’s an extremely powerful woman sitting on a throne, facing forward. And then there were others.

He also did a lot of formal oil paintings, especially of his wife. He loved to depict her in various costumes, so many of these princesses and feminine beings are actually his wife. But she was a painter in her own right, and there are some paintings and portraits of hers that are really wonderful, so I’m sure they critiqued each other’s art.

He loved the outdoors, the rocks and lakes, but she was a city person, and she missed the sophisticated life of Stockholm, so at the very end of their life he acceded to her wishes and they were moving to a new house in Stockholm. But that was a fatal trip, once the Per Brahe went down.

KC So they never even got to enjoy their new home in the city?

FT They never did.

Picture a sandy-haired man who comes from afar, weighed down with empty books and pens, a strange machine he “snaps” again and again—inside our goahti, outside in our bright sun, beside our reindeer, still plentiful now. He smiles at our homes and clothes, but does he know our gods and tales? He must have his own, but why would he go and forget about us—our boys and girls, our land and sky, our stars and fires? He paints our hats and shoes, our knives and belts, on ugly men with pointed ears and potato noses, furry coats that melt into hairy limbs, old Viking chains that hang from necks and wrists. Would we honor him by placing a feather in his cap?

Nordic Spirit Symposium, February 7-8, 2020

Scandinavian American Cultural and Historical Foundation

California Lutheran University, 60 West Olsen Road #2600, Thousand Oaks, CA 91360-2710

https://scandinaviancenter.org/nordic-spirit-symposium/

Information also at: hrockstad@gmail.com Tel. (805) 497-3717