9-15-18

Lark on a String: The Films of Jiri Menzel

By Diane Sippl

Like a bird on the wire,

like a drunk in a midnight choir

I have tried in my way to be free.

Like a worm on a hook,

like a knight from some old-fashioned book

I have saved all my ribbons for thee…

I saw a beggar leaning on his wooden crutch,

he said to me, “You must not ask for so much.”

And a pretty woman leaning in her darkened door,

she cried to me, “Hey, why not ask for more?” …

Judy Collins, “Bird on the Wire,” in Who Knows Where the Time Goes, 1968

A dream fulfilled is the grave of creative activity.

Jiri Menzel

Bird on a Wire

A man moves with the best talents of his time and place, the literary giants and the leading lights of the theatre in Bohemian culture, but then his country is invaded and occupied. He has a chance to flee, but he doesn’t. He stays to challenge the oppressive regime and to resist it with his seemingly innocuous art. He wears many hats—writer of plays and screenplays; director for the stage and the screen. Except for the fact that he also practices medicine and writes novels, this man could be Jiri Menzel, but in fact the one described above is his predecessor, Vladislav Vancura, whose art Menzel and so many others admired.

And if Leonard Cohen’s 1968 song “Bird on the Wire” evokes the moment Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia and crushed the “Prague Spring” (the brief period after de-Stalinization when the thaw of imposed social realism had allowed the Czech New Wave in cinema to blossom), then ironically, another song on that same album, “Partisan,” easily evokes Vancura’s era when, as a proponent of the literary avant-garde along with Kafka and others but also as a Communist, he fought in the Czech underground resistance to the Nazi invasion of the country.

Vladislav Vancura, whose novel Capricious Summer (along with Jaroslav Hasek’s The Good Soldier Schweik) has been considered one of the “twin masterpieces of Czech comic literature,” was detained, interrogated with futile results, tortured, and killed by the Nazis. Menzel’s work may have been banned or upended beginning in 1969, but he survived to make films then and in less severe times. (For example, he adapted Capricious Summer for the screen in 1968, with a hugely popular reception in Czechoslovakia at the time.)

However, Larks on a String, made in 1969, only three years after his Oscar-winning Closely Watched Trains in 1966, had to wait 21 years to pass the censors; it then went on to win the top prize at the Berlinale. It was followed by Secluded, Near Woods (1976), Cutting It Short (1981), The Snowdrop Festival (1984), My Sweet Little Village (1985), The End of Old Times (1989), and I Served the King of England (2006), all made in Czechoslovakia. Each of these nine films as well as an eight-hour documentary called, Czechmate: In Search of Jiri Menzel will be screened in Westwood (usually as double features) by the UCLA Film and Television Archive at the Billy Wilder Theater over three weekends from September 14th- 29th, 2018.

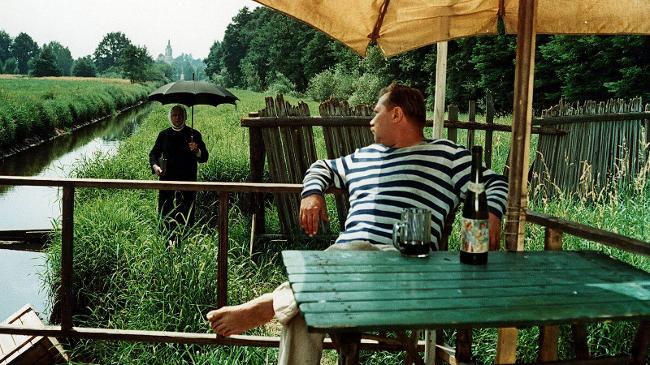

Capricious Summer, Jiri Menzel, 1968

Summertime Blues

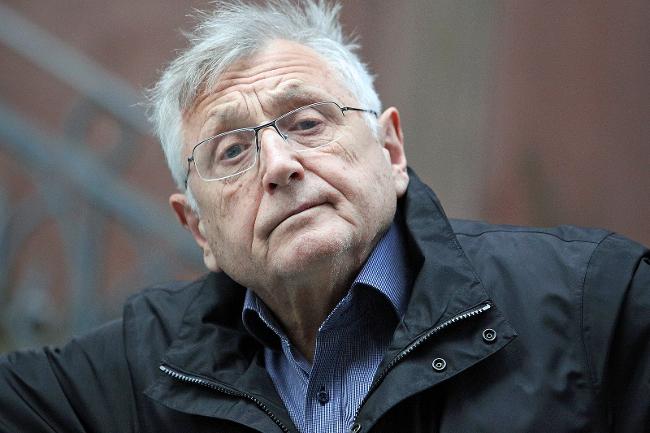

Menzel, this year celebrating his 80th birthday, has worked throughout his entire career in Prague’s theatre arts, of which he has often spoken as his “first love.” In 1968 when he made Capricious Summer, Prague, with a population of hardly a million people, had twenty legitimate theaters, usually with their own repertory companies, as well as two opera houses, and concert halls, not to mention cinema venues. Menzel was a regular at, for example, the Semafor, and he worked as a director at the Drama Club. Actors at these avant-garde theatre companies were a steady staple for the best of Czech films of the era, often lending it integrity and a certain identity. One of those actors was Menzel himself, who enjoyed performing in his own films and those of others. For the sake of argumentation, one facet of the “Menzel Method” might be coined this way, as he put it in 1968: “the ultimate in the art of acting is to be able to say ‘Go stick your head in a bucket’ the same way you say ‘I love you’ and vice versa.”

Just as Czech cinema from its inception at the very beginning of the 20th century was always working hand-in-hand with the National Theatre for the best of actors and scripts, for a century now there has been a close relation between film and the other arts—literature, painting, and music, for example. That connection extended beyond national borders. Jiri Menzel was greatly inspired by both Renoirs, the Impressionist painter, Pierre-Auguste and his filmmaker son, Jean. We need only look at the 40-minute pastoral, A Day in the Country (1936/1946) when it comes to catching the feel of Capricious Summer and the way in which its bucolic atmosphere sings a song of time passing by.

The use of narrative is hardly the point, nor is the concept of character-driven drama where there is little psychology at play in the characters—a bathing house proprietor and his flirt of a wife, a guarded man of the cloth, and a soft-spoken retired army major who idle their summer days away swimming, boating, drinking, and philosophizing until they are pleasantly distracted by a traveling magician who impresses them by doing tricks on a tightrope. They are even more swept up by his blonde assistant who washes up like a mermaid from the stuntman’s gypsy-like caravan and lures each would-be romancer into revealing his physical and social ineptitude. The conjurer, by no means a slick operator or muscle man, is really just a wisp of performance, a bright spot between the raindrops, just enough to cop a free lunch and pass the hat, so to speak. One can only make a fool of oneself, and thus these middle-agers, wary of the passing days and years, do just that. “Fools rush in,” the saying goes... the bath house entrepreneur moves boldly, the old major with swift dispatch, and the clergyman with the love poems of Ovid.

In Capricious Summer we have Jiri Menzel, as screenwriter, director, and actor in his mere twenties, in his two-person ramshackle circus-on-wheels, serving up the pillars of society on a platter. Such a feat is a hand-stand in itself, a “magic act” from the bottom up. The charm of the film goes a long way. We could call it style, which is a language unto itself, but at least one critic considered the meaning of it all as well. Writing in the early 1980s, Yvette Biro looked closely at the acrobat, who of course is played by Jiri Menzel himself:

… there is a sequence when we meet the protagonist as a graceful, gifted tightrope walker doing his daily training. But suddenly some aging burghers arrive and start to get anxious about him: ‘Are you not afraid you’ll fall down?’ they ask and grasp the support, shaking it with full apprehension. He keeps going ahead, but the brave men cannot stop either. They perhaps want the Certitude of Truth. They shout from nervousness and shake the support more and more, until they succeed in pulling it down. In this way, they indisputably confirm the danger of tightrope walking. Does this mean that the clumsy, shy, short-sighted clown, as he is, would necessarily be condemned to fall? Or just the contrary: he could be splendidly triumphant if… if some other clumsy, shy, short-sighted (narrow-minded) external forces did not insist too much on intervening? The question remains open. We will never know whether he really would have been able to fulfill his rather daring mission or not.

In her article, “Pathos and Irony in East European Films,” Yvette Biro went on to explain that irony is not concerned with the naïve issue of who is right but presents conflicts among various people, develops them from various points of view, and refuses to arbitrate. There is no logical character development or progression; rather there are “forceful lunges toward genuine experiences.” Above all, she saw Czech New Wave filmmakers shuddering at a world devoid of mystery.

In an interview with Czech film critic and scholar of literature and cinema, Antonin Liehm, in 1968, Jiri Menzel talked about meaning and truth as follows:

… I prefer truth that is a bit foggy, unclear, but that remains vital with the passage of time, compared with something very precise and pigeonholed, something definitive that has an odor of dead literalness about it. You can’t express anything with a simple sentence or summarize it in a definition. As soon as it’s out, you’ve departed from the truth. Whenever I do it, I always get the impression that I’ve just brushed past the truth, past reality.

Beyond the Clouds

Jiri Menzel knew what he was doing when he turned to Vancura’s novella for his second feature film: Vladislav Vancura was a bold man who took bold strides, but in many directions. Beginning his education with the pursuit of fine arts, he then took up law at Charles University. Unfulfilled, he became a physician and then a writer and chronicler of Czech history. Not only did he write and direct plays and screenplays, but he experimented in his novels, employing poetic devices and a play between various layers of his language.

The words themselves were often drawn from both very old, somewhat archaic sources of the national literature and also the current colloquialisms, which meant from a “high” language (such as the 16th-century Czech version of the Bible) as well as a “common” one with somewhat vulgar idioms. He became known as a “poet of fiction,” and his particular language made his books very popular all the while they showed readers how they could assimilate his new forms of expression. His Capricious Summer employed a number of grotesque elements as well, even if it played them for ambiguity. And his prose very often fell into extensive dialogue, resembling that of a play, all the more amenable to showing off speech patterns at once lofty and robust, erudite and earthy.

Yet the lyricism Vancura masters plays not so much on the men’s banter about business, spirituality, and war as much as on the “strange air” between their desires and their actions, their passions and their deeds. The bucolic scenes Vancura created for the Czech “day in the sun” between the wars, the circus and its hurdy-gurdy music nudging unbreakable personalities doomed to act, even to their demise, registered ironically for Vladislav Vancura’s fate, he himself an unbreakable spirit acting boldly against fascism, which inevitably took him down. In the same vein, the optimistic setting in the novella translated well into a film destined to be made and shown in the “Prague Spring” of 1968, having missed the opportunity to compete at Cannes that May (where the filmmakers themselves took the festival down), but not the fate of repression in store for August, that “capricious summer” in Jiri Menzel’s Czechoslovakia.

Capricious Summer

Director: Jiri Menzel; Producer: Zdenek Oves; Screenplay: Vladimir Kalina, Jan Libora, Jiri Menzel, Vaclav Nyvlt; Cinematographer: Jaromir Sofr; Editor: Jirina Lukasova; Designer: Oldrich Bosak; Music: Jiri Sust.

Cast: Rudolf Hrusinsky, Vlastimil Brodsky, Frantisek Rehak, Mila Myslikova, Jana Preissova, Jiri Menzel, Bohus Zahorsky, Vlasta Jelinkova, Alois Vachek, Bohumil Koska, Karel Hovorka, Antonin Prazak, Pavel Bosek.

Color, 35mm, 75 min., in Czech with English subtitles.