12-12-16

Interrogation: Vetri Maaran on Visaaranai, India, and Cinema

By Diane Sippl

Many filmgoers today might be surprised to discover that over 60% of India’s cinema output is neither Bollywood in style nor Hindi in language but hails from South India where films of many genres are made in Tamil, Telugu, and Malayalam. There, Tamil Nadu has been producing films for at least a century, and today it alone makes over 250 films annually, more than all European countries combined.

Relative newcomer to this rich legacy is Vetri Maaran, whose second feature, Aadukalam (2011) won six National Awards, the most ever in the 63-year history of the award. He is currently in production with a $30 million trilogy, North Chennai, a 35-year epic of the labor unions of the harbor, black money, and gangster activity – a true story and one of the most expensive projects ever of Tamil cinema.

Vetri Maaran’s third feature, Interrogation (Visaaranai), takes us first to nearby Andhra Pradesh where four innocent Tamil migrant workers are coerced into participating in a murder plot behind a state election that threatens their security, their freedom, and their very lives.

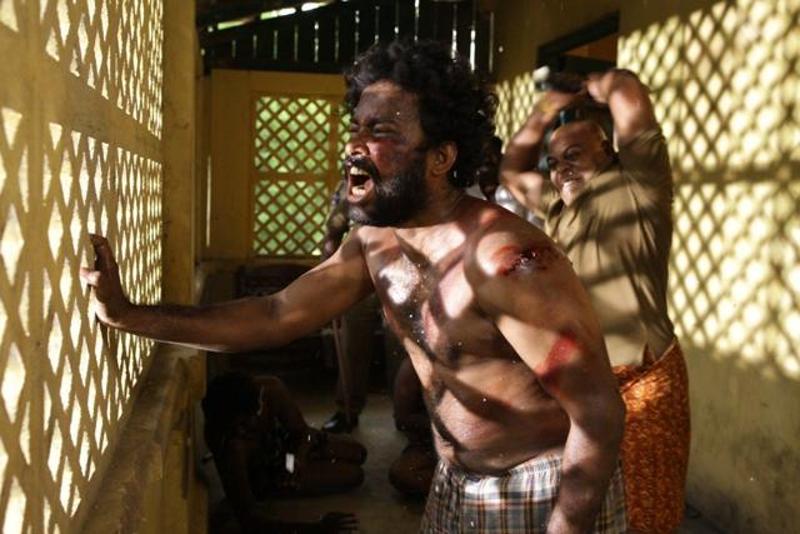

A runaway adolescent pedals to work at dawn from the lawn where he sleeps. He vows to protect a domestic worker he swoons over from her abusive boss, and a young friend meets up with them looking for a job. Before the day begins, the boys and their two friends are jailed, then tortured, and forced to confess to a crime they do not know.

Shot on location partly in a real police station from the colonial era and in chronological sequence so that the story was revealed to the actors and crew only scene-by-scene as the action and dialogue were developed with the director, the filming process for Interrogation was an organic one and held the cast in suspense as the film does the audience who views it. The eerie, minimal score built around silences and the rhythms of world ethnic music lets the film resonate globally in accordance with its widespread social issues.

Winner of the Amnesty International Italia Award when it opened in competition at the 72nd Biennale Venice International Film Festival in the Orizzonti category, Interrogation was also chosen from some 1,500 films (the annual output of the country producing the largest number of films in the world) as India’s submission for Best Foreign Language Film at the 89th Academy Awards.

Crafted with the character point of view of South India’s presumed “dispensable” youths of today, Interrogation not only lets us identify with the downtrodden who are forced to fuel the tyranny of the higher-ups, but it carries our empathy through to a true catharsis in a tragedy of the common man for the 21st century. Finally, the “interrogations” we follow of four adolescent boys and of an accountant they are forced to abduct become our own investigations into the “case of doubt” practice by which an estimated 30% of India’s police cases are “closed” today, making victims of youths under 25 years of age.

More than a police procedural, Interrogation is a political panorama-in-time as it exposes a web of corruption infecting an entire socio-economic system and launches a critique of all hierarchies of exploitation via a bottom-up perspective of historical and contemporary India. But beyond this, if cinema can lend a visceral voice to the silenced, then Interrogation unleashes a gut-wrenching shriek to be heard around the world wherever civil and human rights are abused.

A few days after a screening of his film in Hollywood, I caught up with writer-director Vetri Maaran in London via Google Hangouts and was excited to engage him in the following conversation.

The Story

KINOCaviar People refer to Interrogation as a crime drama, a film noir, a thriller, a police procedural, and a docudrama. Yet to me it doesn’t quite fit into any of these genres. Can you describe any special way that M. Chandrakumar’s memoir, Lock Up, was written, in terms of structure and style, and how much of that form you wanted to keep in the film, such as the voice or the narrative?

Vetri Maaran I started working on the script after I got the rights from Chandrakumar. In the first place what excited me about the book was – ‘excited’ is the wrong word – what motivated me to make this into a film was the truth the book was dealing with. When I read the book I understood that it was not an isolated incident that was happening to Chandrakumar, and it was not something that happens only on India. It’s something that is happening around the world and it’s something that needs a representation. And it’s such a deep grief that I felt it needed to be shared. So that was the first thing.

And the second thing was the way he had written it – the way he’d expressed the detail, the kind of procedure the cops were using against innocent people like him, and how subtle the bits of information were throughout the book. And those minute pieces of information made the whole arc of the drama for the reader. That was very interesting for me, and I decided that it should be the way this whole story was being told.

And then to do that, I had to have two things in it, because Chandrakumar had written of his own experiences, and if I made that alone into a film, there was a possibility of the film being understood as the police going against people who don’t have money, who don’t have power, who are immigrants, who are expendable. But that is not all that’s the case – the police can go against everybody if they want to – and not just the police, the whole system.

So the system can take on anybody it doesn’t want within the system. That’s what happens, and for which I had to work on two other real-life events: the story of the auditor and then the story of the encounter, the killing of the three boys. That was another story that happened, at a different time within Tamil Nadu. So I brought these three real-life events together, and we wove them into one whole film, to give the effect that it has today. And also, we wanted it to be a kind of reading on the policing system within the country and, on a larger scale, around the world.

KC Did you have to use any fictional devices to write the script or were there reliable documents that reported the way the killings had happened?

VM Chandrakumar’s story of his experiences was during 1983 and it ends with the boys being released from the court. The boys were shot in 2003. And the auditor was killed in 2009. So these three separate events actually happened at different points in time, but they all said one simple thing – that the system is going against the powerless and those who are ‘expendable’ in order to safeguard its own self. So that was the connecting factor for me to bring all these three real-life events to look like one story.

KC What about the police inspector from Tamil Nadu, their own state, who initially tries to stand up for the boys?

VM The policeman is my fictional truth to tie down these three real events. So he goes through all three separate stories to make them look like one.

KC But the details of how the boys ended up getting killed in 2003 – were they available for you?

VM There are no proper documents on it; the documents have been created by historians who are appointed by the system, so they don’t talk about anything that really happened. But there is the people’s view on it. We have incorporated some neighbors who were checking out what happened; it went into the film. They have spoken it out and it was on some blogs and people were talking about it. I had to talk to some of the cops within the police force who were involved in that operation.

KC So you did talk with them, but you didn’t necessarily get what you considered reliable evidence.

VM There are no clues, but those who were involved told me that these are things that happened, so we went on with that.

KC With the reports that you got from the people and the blogs –

VM Yes.

KC You know, in working for a studio there is often the pressure to re-do the story, or they bring in another screenwriter… but do you feel that as an independent writer-director, you had total freedom to tell this story the way you wanted to tell it, in the end?

VM Yes, with this film I have really to say that I had 100% freedom, and I didn’t have to make any compromises for an external factor – let’s say if I’d been with a studio, maybe I’d have had to do something for the studio, but with this one, I was just making it for myself. I was working for the betterment of the film, and I had no pressures whatsoever.

When we were making this film, monetary benefits were the last of our concerns. Everybody in Interrogation got involved because we all thought of it as a responsibility to talk about this, and we really took it as a duty to do it. And we all had to give up a lot just to make this happen. It’s really fulfilling to see the film coming up this long and being discussed and watched by so many people. That’s more important for us.

Independent Filmmaking

KC Did you have any problem raising the money to make the film or to get it distributed?

VM Actually, my producer for this film is a very popular actor in Tamil. His name is Dhanush, and we have been working together for the past ten years. For my first two films, he was the actor, and for my next film he’s the actor and producer, and we have come together to produce a couple of other films as well. So we have always been in a good relationship. We’ve been sharing the same interest in terms of subject matter and the kinds of films that are being made. And when I pitched the idea, he was ready to support the film and raise the funds.

I never had any issues in making the film or, for that matter, marketing the film in India because we both, together, have made a lot of successful films, like three or four, and this one also opened very well domestically. It was commercially successful in terms of people watching it and getting back the money, so it’s a good one – it’s a good outing.

See, I am an independent filmmaker for this film, whereas on my previous films I’ve worked with bigger stars and we’ve made a lot of money as well. My previous film won six Indian National Awards, which is a big thing – which is the highest, actually, for Indian National Awards. So there is an expectation for the films that we make.

KC Did you have any conflicts with the government or individuals – any pressure to embellish or heighten or soften any aspects of the film, such as the visualization of violence, the portrayal of issues, the references to key people or events?

VM It was all my own choice. See, when we talk about violence, I want to call up one important thing. Chandrakumar said, ‘I have written only 40% of what I underwent there. I had to avoid writing a lot of it because I didn’t want my daughter to read this book some day and realize that her father had been forced to undergo all these things. So I didn’t write them.’ And out of the 40% he had written, I used only about 20%, which is to say, whatever I have depicted is less than 5% of what actually happened to him.

And while writing these sequences of brutality, I felt very responsible, and that responsibility was to document what was happening there and what is happening there, and it was no intention of mine to indulge in violence or to shock my viewer – nothing of that sort. I just wanted to document something that has happened there, and not just to one person, Chandrakumar, but to millions of faceless people like him whom we had to represent through this film.

So that was a bigger responsibility for me, and I was very selective in showing what needs to be shown. There were certain instances where there was too much blood. I just went on to black-and-white in order to reduce the gore factor. Then the two gunshots in the head, like when this boy Afsal is being shot, are black-and-white; I didn’t want to show the blood and gore. I was trying to refrain from doing all these things throughout the film. But at the same time, I had the responsibility of capturing what happened then, as it happened. That’s why I had to deal with that, and it was my own choice of how to show it. And even the Indian censor board didn’t have much of an issue with that.

KC So did you have any problems from the Indian censor board at all?

VM No, because when we make films, every region has its own individual censor committee. In Tamil Nadu, whenever I make a film, they know that I don’t make films just to make money; they know that I am responsible in making films, so when I showed the film, they just wanted me to reduce the duration of a couple of scenes, and I said, ‘Okay, I’ll reduce them.’ I did reduce a few scenes for them. That’s it. There’s nothing else. They were very appreciative of the film.

Cinematic Form

KC Interrogation uses a noticeable visual aesthetic of lots of vertical camera angles – either very high or very low – dramatic lighting and shadows, occasional shifts to black-and-white footage, and proscenium framing that lends a voyeuristic touch to the film in the sense that we’re peeping down hallways or through obstructed views – we can’t see as much as we would like to find out. Does this style stem from the empathy you want to gain from us for the four young protagonists?

VM You actually noticed a lot, you see. One thing that I would like to add onto that list is the lighting scheme that we used. The first half of the film, in the Andhra Pradesh police station – the first 45 minutes – is all high-contrast, light and shade, only two categories, you know – it’s good guys and bad guys. But then as the film progresses you realize these cops who are being the bad guys do have a vulnerable spot and they are also in a fix.

That’s when the film moves on to the next phase, when KK comes into the film, and the second police station’s operational staff. It becomes more filled. You don’t see the contrast between the good and the bad, the black and the white; there is more gray space, more balance.

When we get to the end of the film, when these boys go into the marsh, they run, they escape, then it again shifts back to the black-and-white lighting. There is no gray area. It falls into a black or white, either good or bad. That’s where it all stands.

And then the lenses we used, and as you mentioned, the use of cameras from top angles and watching the characters through something in the foreground giving the effect of a more hidden, clandestine camera – these are the factors creating the reality of the film and the devices that we used to tell the story that way.

Characters and Actors

KC When we hear the police slap labels on the characters at the beginning of the film such as ‘Al Qaeda’ and ‘ISIS’, in the U.S. we call that racial profiling. Are the four protagonists downtrodden due to religion or ethnicity or caste or because they are homeless/migrant workers?

VM This film is about the caste issue, the lower caste and the minorities as well – the Muslim minorities and the Christian minorities – especially the Untouchables, the lower-caste people within the society. They always end up doing the menial jobs, they always end up being the migrants, they always end up being in trouble. So say, for instance, the boy who has gone to watch a film and has this name of ‘Afsal’ – Afsal is a Muslim name. Because he is a Muslim, they ask him if he is Al Qaeda or ISIS, and then this boy says, ‘No, sir, I am Tamil.’ Tamil is immediately ‘Liberation Tigers of Sri Lanka’. So if this boy had not been a Muslim boy or a Tamil boy, he might not have ended up being in trouble like that. And these boys like Pandi, Murugan, and Chandrakumar – all these boys are from the lower caste, and Inspector Muthuvel is also from the lower caste, even if he is a part of the Indian reservation system: lower-caste people have to be given some 30% of the job offers in all government positions.

There is one scene that explains the situation when they’re talking about silencing the Intelligence Inspector in the police station and the Assistant Commissioner says, ‘Sir, that guy’s also our caste. I can talk to him.’ And the DCP says, ‘Then let’s pay him the money, also – let’s give him a share as well.’

Then in that same scene when Muthuvel tries to save the boys, he says, ‘Okay, you decide it. You guys do it. I’m leaving.’ He gets up. But the Assistant Commissioner stands up and says, ‘You have to do it or else you will be in trouble.’ When Muthuvel doesn’t have any other option, he sits down, and the Assistant Commissioner says, ‘You low-caste guys, you come in through this government quota.’ Now all the other cops are upper-caste guys and this one guy alone is the low-caste guy, and he’s trying to do justice for the boys, but he’s being silenced.

And we can also mention that one particular shot in terms of lensing. So this Inspector Muthuvel stands up. He decides to leave. And then the AC stands up. With a wide-angle lens, the AC’s in the foreground and Muthuvel is a little bit away, in the background. The focus is on Muthuvel. The Assistant Commissioner of Police looks so big in size and Muthuvel looks so small. That’s the kind of pressure the upper caste has over the lower caste, and he’s forced to accept doing something that he really is not convinced about doing. So this is a whole subtext that is there in the film that needs to be read, too.

KC Are all four of the boys (the protagonists) Muslim, or only the one?

VM No, one boy is Muslim. The other boys are Hindu boys but lower caste.

KC And are all the low-caste boys of the Untouchable caste?

VM It varies. The Brahmins, or the other upper castes, look at those who are next in the hierarchy of castes, down to Untouchables; then those Untouchables to the Brahmins look down upon the next…. You see, being low-caste does not necessarily mean being Untouchables, but they are out of the acceptance of the normal society.

And also one more important thing – there is no caste system in the open as it used to be some hundred years ago; yet on a larger level, it does exist still, but unsaid. The upper-caste person has favoritism. He is nepotistic toward his community’s youngster who comes into a government job, and he uses this favoritism toward his community’s people. It works in an unsaid, hidden way. It’s the hidden agenda.

KC So if in real life the author of Lock Up works as an auto rickshaw driver today, in the film he does what?

VM In the film, he works in a butcher shop.

KC And Pandi is the one who works in a small shop on the street – as a shop assistant?

VM Yes. And Murugan works in a hotel. And this boy Afsal has come just three weeks prior to the incident that happened. He’s come to Guntur looking for work. And then these boys are taking him in. So Pandi is trying to put him to work in the shop where he is working.

KC You directed a huge ensemble of many actors over a shooting schedule of 42 days. Were there any special challenges in working with the actors?

VM No, I normally don’t have issues working with actors, and also, to be precise, there were only four professional actors, and the rest were all amateurs or new actors. Pandi and Murugan were professionals. And KK, the auditor, was a professional, and the Inspector who gets shot in the end also is a professional. Other than that, all of them are new people.

For me, when I choose to have someone play a role, I make sure that person fits the role. I have an image when I write the character, when I conceive the character. If actors can suit that frame, I’m kind of ready to take them in, and then I don’t pressure them or force them to be a certain way. I just let them be themselves and then I capture them. That’s it. That’s how I work.

KC It feels that way, but it’s hard to believe. The acting seems so natural. The whole film is quite remarkable in terms of the skill and the professionalism and the way it’s all put together. Was it 42 days that you spent in production and shooting it? Is that correct?

VM Yes, I shot 40 days and for 2 days, I had to re-shoot some portions. Technically speaking, it was a 40-day shoot.

Language and Culture

KC We often forget that India is a country of many languages, and some scenes of the unjust procedures in the film have to do with language gaps and choices. How did you navigate this situation in the writing?

VM In India we have around 24 to 26 official languages, and we have hundreds which are not official. Many are just spoken languages without script. There is one called Tulu which doesn’t have a script and they make films in that language. A Tamil-speaking person from Tamil Nadu will not understand Telugu, which is being spoken in the next state, Andhra. Or none of these guys living in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh will understand Malayalam, which is being spoken in the next state, or Kannada.

South India consists of four states, four different languages, four different cultures – Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala, and Andhra – and none of us shares the other’s language. And most of us don’t speak Hindi. Of course in Karnataka a lot of people speak Hindi. In Kerala they speak Hindi. In Tamil Nadu and Andhra, we speak less Hindi. So I think English is more the language of communication within India. I communicate in English within India.

When I was writing the film, the exciting part for me was the language barrier within the country and how important it becomes. To understand one’s language and to live within one’s own country is becoming challenging for us. That’s very – what to say – that’s very Indian to share with the world. And the biggest challenge we had was how to tell this to a non-Tamil or non-Telugu-speaking viewer. That is when we decided to go with two colored subtitles.

The languages in the film are mostly Telugu and Tamil. So we had to use the different-colored subtitles so that a non-speaker would understand the difference, and the importance of language, the difficulty of language, within the country. We used the yellow for Telugu and the white for Tamil.

KC Will the film be distributed in India in multiple language versions?

VM We’re not dubbing the film in India. It has subtitles, and we’re releasing the film as it is. We had a small release around India, and it did have subtitles.

KC How will access on Netflix change this film’s reception?

VM I feel that the visibility of the film has grown immensely because of Netflix, because after it was on Netflix we got someone from Brazil saying the film is good, and someone from the Philippines has watched it and says it’s good – these are places a Tamil film would not normally reach.

India Today

KC You’ve reminded audiences that human rights violations – in particular police brutality and abuse – are prevalent worldwide, but can you speak to issues in South India? Is there police abuse there today? Do people worry about corruption in election processes or results? Are there still ‘internal machinations’ within law enforcement and political intervention of police/courts/rising citizens in government processes?

VM You see, policing is only one phase, or to be precise, it’s the hand of the system. And my opinion is that the system as such is meant to curb, to scare the common man against policing, against the ruling British world. In that political system the policing rule was established by the British rule, and we still hang onto that.

There are a lot of reforms being made in various fields in a country like India. So much is changing, and even the policing system tries to make changes here and there, but I personally feel that the whole system has to be reviewed. That’s my thing. I feel that it’s world-wide.

It’s world-wide wherever you give the power to someone who can do anything to prevent the common man from expressing himself or protesting in a peaceful way. I think that’s a human right – to protest in a peaceful way. And when you’re not being allowed to do it, the system stopping you from doing it is not the right kind of system. We need to change that. I feel that the system needs to be changed. That’s my whole take on it.

KC Okay, what about the opposite side of the coin – your film was selected as the submission from India to the Oscars. Has the government supported the campaign for international recognition of your film, even though it’s independently produced?

VM Normally the government doesn’t get involved, but from this year, it has announced that it’s going to fund a certain amount of the campaign, which is really good. And the moment the announcement came that Visaaranai/Interrogation was the Indian submission, that said a lot about India as a democratic nation. A film which takes on the system in this way becomes India’s submission for the Oscars. I always say that this is the best example we could have to tell the world that India is a democratic country and that creative freedom – the creative freedom of an artist – is very, very much intact here.

KC It’s a paradox for me that I would like to see a lot more of. I would like to see that happen everywhere, and I’m amazed that you’ve achieved it, so I congratulate you on it.

VM Even last year the submission from India – a film called Court – took on the judicial system. So for the last two years, these are the kinds of films that are being selected and sent, and that’s really a very, very, positive sign, I would say.

The Promise of Cinema

KC Well it really impresses me very much. And I have then one closing question. I wouldn’t ask this of everybody, but I think for you it’s really important to comment on it. I’ve been a professor of film history and theory, and I’m a film critic – not a movie reviewer but a scholar of world cinema – and I would like to hear your answer to what you think cinema can do best and how far its power can go. What’s the most that it can achieve?

VM See, I don’t find cinema bringing social reform, and I don’t look at cinema as a medium of making political agendas. I see it as a medium of the common man – at least privately, the common man, and especially in a country like India.

India is the largest producer of films – it makes around 1,500 films a year. So from that perspective, a common man – the common man’s collective unconscious – is influenced by the kind of material given, through unassuming ways, such as in films. You go to a film – you just start picking up certain things from a film, and you feel that, you take the things that come from there for granted.

Say, for instance, gender equality. In Indian films you never get to see that. And that is, in a way, a reflection of the society, and it influences the society internally. It’s a circle. It goes on in a circle. I feel a good film will start a discussion within the society, and that discussion should lead to further, larger movement within the society. That is a good film for me – a film that presents its own language, community, and culture is a good film for me.

And I feel films are an important source of history, especially in countries like ours where we don’t – where there are so many fewer archiving processes. You know, like if we want to see what happened in 1970, we just will have to look on to a film that was shot in 1970. Sometimes what happens in countries like India is that you don’t get to see how the people of those times really lived, and instead you see them trying to imitate some other culture or history. There were times when they made cowboy films in Tamil, where they used to wear hats and ride on horses, or they were dressed like native Americans – they made films of that as well, because of the influence of Sergio Leone and other people. They tried doing all these things. So there is the responsibility of the filmmaker, also. Unintentionally being a historian is also a major responsibility of a filmmaker. Films also are sources of history. These are certain things that I feel that cinema is all about.

VM And one more thing that I want to add about what films are. I always feel film is a marriage between – on the one side you have science and commerce; on the other side you have art. So for any other art form, you don’t need a whole bunch of people. You don’t need 200 people to make any art form except cinema. It has brought everything into it. So when so much comes into play, if a filmmaker doesn’t understand science, he can’t make films. If he doesn’t understand the science, he will not be able to make the film that he is making right now. If he doesn’t understand the commerce, then he will not be able to make his next film. So that’s the thing. It’s a marriage of all these aspects, and it’s so important for a filmmaker to be making film.

And then to be making films you need to have an investor, be it an independent investor or a studio. Someone should be there to invest in your idea, your script or a script that the investor feels is good for you to make into a film. So that’s another aspect I always have in my films.

KC Early on your film, Visaaranai (Interrogation) presents us with a character who, much like us, has come from a late night at the movies. Does that situation position us as spectators in a special way? Is the title meant to turn back to us – to let us see ourselves looking at a film, discussing it, questioning, maybe even making our own “interrogation,” of corrupt systems, of our world?

VM Actually, the Tamil word for this title, Interrogation, was Visaaranai, and Kafka’s Trial was translated into Tamil as Visaaranai. That’s the reason I chose that title. It’s the same story there; even Kafka’s Trial goes on that way. The protagonist is arrested, and throughout the book he’s being interrogated, and ‘til the end, he doesn’t know what his crime was. That’s what happens to these boys as well, so that’s the reason I chose that title.

KC I see. I was going to ask if anybody influenced you.

VM If that’s the thing, particularly, it’s Dostoevsky for me. And Shakespeare, of course. I was a literature student – I did my Masters in literature. Shakespeare is there always, and filmmakers – Akira Kurosawa and Costa-Gavras, Herzog, Oliver Stone. Oliver Stone is a very big inspiration. Lots more, lots more….

KC I’m sure. Thanks so much for the great talk, and good luck!

VM Thank you!

Interrogation (Visaaranai)

Director: Vetri Maaran; Producers: Dhanush, Vetri Maaran; Screenplay: Vetri Maaran; Book Source: M. Chandrakumar; Cinematographer: S. Ramalingan; Editors: Kishore T.E., G.B. Venkatesh; Sound: T. Udaykumar (4frames); Music: G.V. Prakashkumar; Designer: Jacki; Costumes: V. Anand Nagu; Make-Up: A.R. Abdul Razack.

Cast: Dinesh Ravi, Samuthirakani, Kishore Kumar, Anandhi, Murugadoss, Ajay Ghosh, E. Ramadoss, Moonar Ramesh, Pradeesh Raj, Silambarasan Rathinasamy.

Color, 116 min. In Tamil and Telugu with English subtitles.