6-19-22

Treasurer of the Night: Inna Faliks, Piano at The Wallis

By Diane Sippl

On Wednesday, June 22 at The Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts at 9390 N. Santa Monica Blvd. in Beverly Hills, nine new works for piano will be given live premieres by prolific pianist Inna Faliks side-by-side with her performances of the original classics on which they were based. An homage to Beethoven and Ravel, the concert, from 7:30-9:30 pm, is preceded by a Prelude interview with the artist by KUSC’s Brian Lauritzen on the same stage at The Wallis’ Bram Goldsmith Theater at 6:30; tickets can be purchased at 310-746-4000 (Monday–Friday, 10 am to 6 pm) or at TheWallis.org/faliks.

A high-profile performer who tours the world with her recitals and concerts, Inna Faliks is a professor and head of Piano Studies at UCLA’s Herb Albert School of Music. By master-minding the album, Reimagine: Beethoven and Ravel, released on Navona a year ago, she conceived of an ingenious way of crossing musical eras and artistic disciplines at once. When she commissioned six of her colleagues at UCLA (Richard Danielpour, Peter Golub, Ian Krouse, David Lefkowitz, Mark Carlson, and Tamir Hendelman) to respond to Beethoven’s Bagatelles, op. 126 with their own new compositions and three other celebrated contemporaries (Paola Prestini, Timo Andres, and Billy Childs) to compose new pieces inspired by Ravel’s Gaspar de la nuit, some of these artists created works resonant with the source music, some took off on flights of fancy of their own, and some referred back to the original prose poems of Aloysius Bertrand on which Ravel based his three fantasies.

Inna Faliks also gave herself the challenge of performing some of the most demanding music ever created for the piano. What’s interesting is that her concert will feature the new works first before she plays each individual one’s predecessor in tandem, inviting the audience to enjoy and appreciate the vitality of contemporary composers (and perhaps discover something new in the classics along the way).

Crossing Paths

If you ever wanted to trace artistic expression from imagined experience into written words and then again into musical notes, Gaspard de la nuit is proof of how demanding—and exquisite—that rapture can be. Inna Faliks has dared to add two more layers to the process, asking three renowned composers and musicians to then improvise on Ravel’s compositions with their own fresh imaginations and musical visions, creating sounds that she will then, in turn, produce with her own interpretation as a pianist. If all this seems like an unusually tortuous excursion in the arts, at least from verbal to musical and then from artist to artist, try to conjure that it can all be done in scarcely an hour on a midsummer’s night, portentously within the shadow of the summer solstice, as if a chilling encore to Make Music Day the world over.

The Images

Picture this: you are sitting in a garden in Lyon, France and a messy-looking man sits on the bench beside you with a book. “You must be a poet,” the stranger tells you. “I’ve spent my whole life searching for the meaning of Art and its elements. I discovered the first principle, Sentiment, in a little book inscribed, ‘God and Love: to have loved and to have prayed.’ Yet what constitutes Idea in Art? Having devoted my entire youth to studying nature and the works of man, I think the second principle—that of Idea—is Satan. But after a stormy night at the Church of Notre Dame when clarity shone through the shadows, I saw that the Devil does not exist, that Art exists in the bosom of God, and that we are merely the copyists of the Creator.”

This stranger thrusts the book, his own manuscript, into your hands, telling you of all the attempts of his lips to find the instrument that delivers the pure and expressive note, of every attempt to pour onto the canvas (before the subtle dawn-glow of clarity in the shadows appeared) his novel experiments of harmony and color, the only products of his nocturnal deliberations. Then the shaggy old man goes off to write his Will, telling you he’ll return tomorrow to collect his book. The manuscript is Gaspard de la nuit: Fantaisies à la manière de Rembrandt et de Callot.

The next day you re-visit the garden to return the book to its owner, but he doesn’t show up. You ask everyone, “Who is M. Gaspar de la Nuit?”

“He’s probably in Hell, unless he’s out on his travels,” they tell you.

“He’s the Devil!” you realize. “May he roast in Hell. I’ll publish his book.”

You open it to a preface written by Gaspard himself, which explains that the artists Paul Rembrandt and Jacques Callot represent two opposite faces of Art: the philosopher who meditates upon beauty, science, wisdom, and love, grappling with the symbols of nature, and the flashy figure who struts down the streets, picks fights in taverns, swears by his rapier, caresses harlots, and is mainly preoccupied with waxing his moustache.

The Words

Gaspard de la nuit: Fantaisies à la manière de Rembrandt et de Callot is itself a collection of early prose poems written in 1836 by the Italian-born French poet Aloysius Bertrand. Derived from the original Persian form of the word, “Gaspard” means “the man in charge of the royal treasures.” Here “the night” alludes to all that is jewel-like in the dark, mysterious or ominous, and maybe even gloomy and ill-tempered. In 1908, inspired by three particular poems in this collection, Ravel chose the following texts to transcribe into music for his Trois poèmes pour piano d'après Aloysius Bertrand.

“Ondine”

… I thought I heard |

"Listen! – Listen! – It is I, it is Ondine who brushes drops of water on the resonant panes of your windows lit by the gloomy rays of the moon; and here in gown of watered silk, the mistress of the chateau gazes from her balcony on the beautiful starry night and the beautiful sleeping lake. |

"Each wave is a water sprite who swims in the stream, each stream is a footpath that winds towards my palace, and my palace is a fluid structure, at the bottom of the lake, in a triangle of fire, of earth and of air. |

"Listen! – Listen! – My father whips the croaking water with a branch of a green alder tree, and my sisters caress with their arms of foam the cool islands of herbs, of water lilies, and of corn flowers, or laugh at the decrepit and bearded willow who fishes at the line." |

Her song murmured, she beseeched me to accept her ring on my finger, to be the husband of an Ondine, and to visit her in her palace and be king of the lakes. |

“Le Gibet” What do I see stirring around that gibbet? |

Ah! that which I hear, was it the north wind that screeches in the night, or the hanged one who utters a sigh on the fork of the gibbet? |

Was it some cricket who sings lurking in the moss and the sterile ivy, which out of pity covers the floor of the forest? |

Was it some fly in chase sounding the horn around those ears deaf to the fanfare of the halloos? |

Was it some scarab beetle who gathers in his uneven flight a bloody hair from his bald skull? |

Or then, was it some spider who embroiders a half-measure of muslin for a tie on this strangled neck? |

“Scarbo” He looked under the bed, in the chimney, |

Oh! how often have I heard and seen him, Scarbo, when at midnight the moon glitters in the sky like a silver shield on an azure banner strewn with golden bees. |

How often have I heard his laughter buzz in the shadow of my alcove, and his fingernail grate on the silk of the curtains of my bed! |

How often have I seen him alight on the floor, pirouette on one foot and roll through the room like the spindle fallen from the wand of a sorceress! |

Did I think him vanished then? the dwarf appeared to stretch between the moon and myself like the steeple of a gothic cathedral, a golden bell wobbling on his pointed cap! |

But soon his body developed a bluish tint, translucent like the wax of a candle, his face blanched like melting wax – and suddenly his light went out. |

The Notes

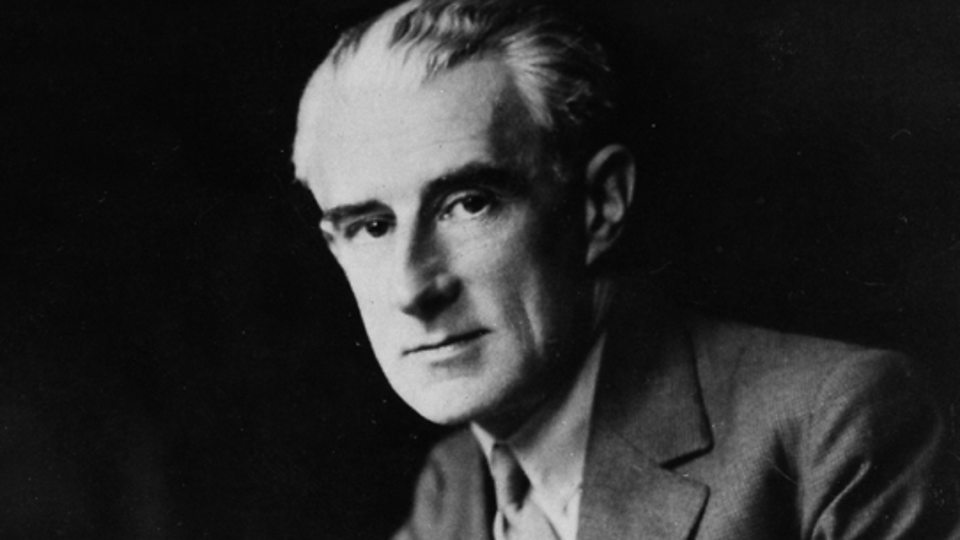

Gaspard has been a devil in coming, but that is only logical since it was he who is the author of the poems. My ambition is to say with notes what a poet expresses with words.

Maurice Ravel

Ravel, himself fascinated by the macabre and grotesque in Edgar Allen Poe—the quivering torment of foul play between illusion and reality in America’s first short stories—was inspired to re-create in music the fear and wonder that Aloysius Bertrand had achieved with Gaspar de la nuit, the first prose poems in French literature.

In the 1890s Maurice Ravel, with his own propensity for the fantastic and the exotic, admired Eric Satie’s experimentation in music; at the same time, he appreciated the innovations of Emmanuel Chabrier, emulated the virtuosity of Franz Liszt, and enjoyed collaborating with Igor Stravinsky. Often acclaimed for his small forms, Ravel could compose with watch-like precision even when his harmony was obscured. Rejecting the label “impressionist” as did Debussy, Ravel’s music was generally less static than that of his predecessor. However, the composer and pianist Ricardo Viñes y Roda, who premiered Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit, claimed that if he performed the nuances and speeds Ravel had set down for “Le gibet,” he would “bore the audience to death.” While Ravel’s piano music was deliberately written to challenge musicians both technically and artistically (with his final movement of Gaspard de la nuit he wanted to surpass Mily Balakirev’s formidably difficult Islamey), it was often noted that Ravel could not perform his own compositions

Evoking interludes of glittering hallucinations, foreboding darkness, and night terrors, Ravel included abundant and fast arpeggios, vague key signatures, and polyrhythms to “paint” Bertrand’s poems in music.

The Music, Music, Music

A successful Ravel interpretation is a finely balanced thing. It involves subtle musicianship, a feeling for pianistic colour and the sort of lightly worn virtuosity that masks the advanced technical challenges he makes in Alborada del gracioso ... and the two outer movements of Gaspard de la nuit. Too much temperament, and the music loses its classical shape; too little, and it sounds pale.

Music critic Andrew Clark, 2013

My music doesn’t need to be interpreted; it needs to be realized.

Maurice Ravel to Marguerite Long

It has often been pointed out that Ravel’s compositions are so minutely calculated and so meticulously delineated that they leave pianists little room to articulate their own interpretations. In performing Gaspard de la nuit, Vladimir Ashkenazy and Martha Argerich have made opportunities to take liberties. Yet consider a contemporary jazz artist such as Billy Childs responding to the widely touted “knuckle-buster” third movement of Gaspard de la nuit, “Scarbo,” within his own idiom and imagination in his composition for Inna Faliks’ performance. Re-imagining the menacing and even dangerous imp who wreaks havoc on a night’s sleep in Bertrand’s medieval chateau, flying and buzzing around in a manner some would describe, quite literally, “like a bat out of hell,” Childs commented about the narrative, “It turned into—in my mind—a sadly familiar American storyline, in which a Black man is being pursued--by the "slave catchers," the Ku Klux Klan, the police...." He entitled his composition, “Pursuit,” calling up this moment in history and yet—or thus—creating again one more fiendishly difficult piece to play. Inna Faliks welcomes the challenge. She masters it with a vengeance.

The Image of the Music

You need to make that wall sing.

Barbara Flanagan, Minneapolis Star

One lasting layer of Gaspard de la nuit exists in its journey across the arts: a towering reproduction of the script of “Scarbo” on sheet music as a mural covering the entire wall of a building in Minneapolis, Minnesota, perhaps both to celebrate and to haunt the passing public with the legacies of Bertrand, Ravel, and Gaspard himself and inspire artists of all kinds to “soar”!