10-27-11

Valery Todorovsky’s Hipsters: Rebels with a Cause

By Diane Sippl

…the hipster was…(a) typical lower-class dandy, dressed up like a pimp, affecting a very cool, cerebral tone — to distinguish himself from the gross, impulsive types that surrounded him in the ghetto — and aspiring to the finer things in life, like very good ‘tea’, the finest of sounds — jazz or Afro-Cuban…

Albert Goldman with Lawrence Schiller, Ladies and Gentlemen, Lenny Bruce!!

The hipster style was assembled in relatively close proximity to the ghetto black: it gave formal expression to an experienced bond, it shared a certain amount of communal space, a common language, and revolved around similar focal concerns.

Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style

The Russian word for “hipsters,” stilyagi, refers to a youth sub-culture beginning as early as the late 1940s after WWII introduced Western clothes, films and popular music to the USSR. Stilyagi were “stylists” from head to toe and morning ‘til midnight, defying Soviet codes for conformity in appearance and behavior by supplanting them with the modes of Western youths, and shtatniki were proponents of the United States per se. Stilyagi were targets of the press and the Komsomol alike and risked expulsion from universities (unless they had “connections,” by blood or persuasion, to Party officials, bringing them even easier access to Western lifestyles.

Valery Todorovsky’s popular hit, Hipsters (Stilyagi) rocked the Russian box office over the New Year in 2008 and racked up a number of Nika awards including the country’s “Best Film.” The screenplay was adapted by Yuri Korotkov from his book, Boogie Bones and the film was directed and produced by Todorovsky by incorporating rock songs from Russian culture of the late 1980s and 90s, sometimes adapting their lyrics to drive home the narrative but other times keeping them in tact for recognition or celebration of their role in creating style.

The film opens with the hipsters in full swing at a party until the Komsomol raids it with scissors in hand, and Mels (an acronym for Marx-Engels-Lenin-Stalin), played by Anton Shagin with a sweet naïveté that would melt anyone, is expected to shear the tresses and slash the dress of vibrant Pol’za (an acronym for Pomnim Lenina Zavety — “We remember Lenin’s behests”). Polly, as the subtitles call her (and throughout, they are only as good as subtitles can be, losing much in the translation of not only Russian, but lyrics and also slang) is played sumptuously by Oksana Akinshina, and she not only thwarts Mels’ directive, but mercilessly seduces him. As in all good musicals, she can’t yet admit to herself that she has fallen just as hard for him.

Mels is instantly hooked. He learns to dress, dance, and play the sax in good stilyaga form, and he changes his name by dropping the “s” — significantly, Stalin. This all endears him to gang leader Fedor (Maksim Matveev), whom we know as the carefree Fred, son of a Soviet diplomat who lives “the good life” and “gets down” at the same time. All is well until the jealous one-time ally of Mel makes waves; Katya (Evgenia Brik, pretty even in her frumpy gray uniform) denounces Mel as a traitor. Soon thereafter Fred is co-opted as a career diplomat (so that he can actually go to live in the U.S.), and their friend Bob is busted for black-marketeering. Other surprises come along, “expected” in a lifestyle defined by spontaneity.

Todorovsky has said that all his life he dreamed of making a musical, but everyone kept telling him that the genre wasn’t a Russian one, and that Russians don’t even accept musicals on the stage. “I think this is the first Russian musical since the 30s and 40s and I still wanted to make it,” he commented at the Seattle International Film Festival. What most in the audience probably didn’t know was that in 1936 a very particular musical, Grigori Aleksandrov’s Circus, appeared on Russian screens, actually adapted from a Russian stage play, Under the Big Top, by I. Ilf and E. Petrov.

When in the early 1930s

Aleksandrov accompanied Sergei Eisenstein to America

for a project at Paramount,

the young assistant director was smitten by what he saw on-screen: the studio’s

musicals by Ernst Lubitsch and Russian emigré Rouben Mamoulian, and then also

those at Warners. Alexandrov wanted to

work in the genre that could make a film star of his wife, the singing-dancing

Lyubov Orlova. Circus featured impressive choreography, complex design and

cinematography, and some of the most popular Soviet songs of all time. Not only that, but Circus (Tsirk) looks like

a clear inspiration for Hipsters on

many levels, and it appears that Todorovsky’s film refers to it quite

explicitly in its narrative, its choreographed images, its camera style and even

a song.

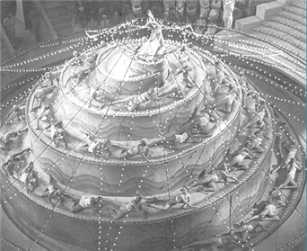

But Todorovsky also merged the stilyagi of the 50s with the Russian rocker rebels of the late 80s. “I took their songs because I thought they were closely related,” he tells us, “and as a musical producer I reworked them and turned them into a musical. They all originally sounded different.” The scene of the Komsomol meeting in which Mel is expelled is set to an orchestration of “Chained by One Chain” from the 1980s by Nautilus Pompilius. Throughout the film, Roman Vasyanov’s rapidly moving camera with its endlessly shifting angles and Alexey Bobrov’s editing that is perfectly in sync with it deliver a kaleidoscope of

images, often from a stunningly high angle, such as in Mel’s and Polly’s love scene, playing up the detached camera’s self-reflexive compassion for the hip but vulnerable youths. Meanwhile the vibrant colors pop as the hipsters’ own names for places and streets are penned onto the screen. Gorky/Tverskaya Street, a sort of “Main Street” of Moscow, is named “Broadway.”

Todorovsky did a bit of ethnographic work in preparing his film, talking to one-time Russian hipsters who are alive and well today. He actually culled his rainbow bulldog from one of their stories. They saw the dog as an emblem of identity that they strutted in public, proud of being “different.” According to the director, Russian hipsters expressed themselves not just through their own colors and clothes and cocktail parties with plenty of couches and beds, but precisely through their music and dance. And these two dimensions of the film transform it from a social document into a cultural myth with fairy tale elements borne on the wings of singers and dancers. The hero himself becomes a musician, which only serves to highlight the appeal and the power of music in the insignia he chooses to wear on his shirtsleeves.

Commenting on how contagious the rhythms and vibrations of rock ‘n’ roll, jazz and blues are, Todorovsky claims he danced right along with the actors: “I couldn’t stop myself. No one in the crew had any experience making musicals — nobody, including the choreographers, music director, actors, and director.” To see Boris-turned-Bob (the talented actor-turned-comedian-dancer Igor Voynarovsky) teach Mel how to swing his hips and rock on his toes is worth all the film just there. Hipsters is one musical that doesn’t skimp on a primary element of the genre — movement. Its dance scenes are as potent as its dynamic camera sweeping over the film’s wide frame in scope format. Roman Vasyanov knows just how, and how much, to move the camera.

But beyond Mel’s drive to fit in with Polly’s hip crowd, this young Romeo also wears his heart on his shirtsleeves, from the beginning to the end of the tale, which is the strongest aspect of Todorovsky’s film. Mel’s aspirations, affections, demeanor — his very face, let alone his conscious choices that leap from his heart faster than from his head — cast him as so innocent, pure, and good-willed that all we want is for him to grow into “his own element.” And maybe, in this film’s terms, that’s the best definition of “hipster” there is. As the director sees it, to be oneself in the Soviet Union of the 1950s was a tall order, and we want Mel to rise to it.

There is a turning point in the story — some say that the film starts to sag there — when Polly gets pregnant and money gets tight. Fred has taken all his privilege and gone off to America, the land of milk and honey and real hipsters, so he thinks. But he comes back and says there are none there. “He’s lying,” says Todorovsky. There were hipsters; he just stopped seeing them. He had already turned into the ‘man in the suit’.”

But his return visit, an emblem itself of how young Russians “got their hands on” the life of The West during the Cold War era, is providence for Mel, in the form of Fred’s gift of a gleaming, luscious saxophone, maybe the image with the biggest iconic value in the film. If the “suit” for Fred means co-optation by Western “civilization,” and not only that, but also the bygone zeal for personal taste and expression, and the wavering and fading of freedom in any youth subculture that eventually comes apart at the seams, then the sax for Mel is the height of his own free spirit in The East. The sax, ever regarded as the “bastard” instrument because it never made the ranks of other horns to enter the legitimacy of the orchestra, at the same time carries a punch that subverts that classical definition of music. Not only is it appropriately the “right arm” of a counter-culture figure such as Mel, but it’s his very essence. Between the narrative and the visual aspects of the film — and furthermore, between the musical and visual aspects — the sax is never restricted to one symbolic meaning, not any more than music can ever be reduced to a single sign or reference. The saxophone, mythically and realistically, delivers a “special little bundle” to Mels and Polly, their biggest challenge in the film and one that far surpasses that of Fred’s coming of age faster than Elvis. Says Todorovsky, “Everything was building to this, because Mels wanted so badly to play sax with this black guy, merge with his culture and music; and we were simply giving him all this.”

True to form in musicals and conjuring homage to Russian musical cinema and popular music itself, to those bold and playful and free-spirited works of earlier years that transported cultures, arts, and values on the wings of curiosity, admiration, and longing, Hipsters both draws from and advances an iconoclastic mode of Russian filmmaking — and, according to both critical praise and box office success alike, the taste for this particular “good life” in Russia is alive and well.

Above: Director-Producer-Writer Valery Todorovsky

Hipsters (Stilyagi)

Director: Valery Todorovsky; Producers: Leonid Lebedev, Leonid Yarmolnik, Vadim Goryainov, Valery Todorovsky; Screenplay: Yuri Korotkov (based on his book, Boogie Bones); Cinematographer: Roman Vasyanov; Editor: Alexey Bobrov; Music: Konstantin Meladze; Libretto: Valery Todorovsky, Evgeny Margulis; Art Director: Vladimir Gudilin; Costumes: Alexander Osipov.

Cast: Anton Shagin, Oksana Akinshina, Evgenia Brik, Maksim Matveev, Igor Voynarovsky, Ekaterina Vilkova.

Color, 35mm Scope, 125 min. In Russian with English subtitles.