9-29-13

German Currents: The Flow of the Year

By Diane Sippl

“German Currents: Festival of German Film” will showcase a cross-section of the country’s highlights in cinema production at its seventh annual event, held this year at the American Cinematheque’s Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood from October 4-7, 2013. A wide spectrum of programming will encompass theatrical, documentary, and short films and also sample a diversity of genres and settings, with co-productions hailing from Austria and Switzerland and location shooting in Africa, Canada, Asia, Australia, and the U.S.

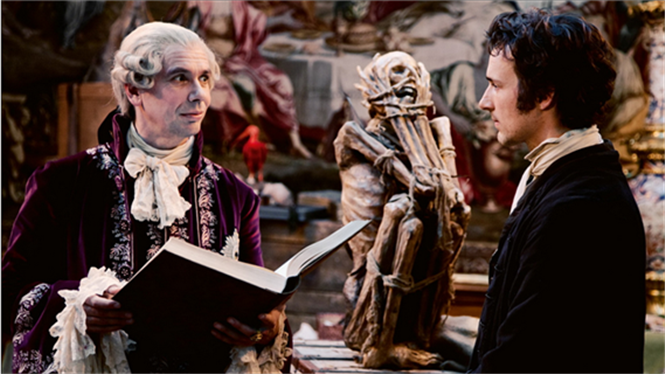

Beginning with the Gala Opening Night, the “wide angle” of this year’s “German Currents” will be established in Detlev Buck’s Measuring the World, which takes us not only across continents but also across genres. Based on Daniel Kehlmann’s best-selling novel, the film has been referred to variously as a life-adventure, a double biography, a historical epic, a visual fable, a playful re-imagining, and a humorous tale that uses science fiction and three languages, German, Spanish, and French.

How else to portray the lives of two famous Germans who took stock of their world(s) in dramatically inverse ways?

One is an early genius living in near poverty; the other, a boisterous go-getter from a noble family. Both win the support of the Duke of Brunswick in the early 19th century. While mathematician Carl Friederich Gauss pursues his interior journey cerebrally through theories and figures, naturalist Alexander von Humboldt engages life physically through global exploration. “Most human beings don’t know why they are on earth, they accept their destiny and try to survive,” a tagline tells us, but these two extraordinary men “fight their predestination.” While one comes to know the surface of the Earth through abstractions, riddles, and disquisitions of arithmetic, the other finds unknown cultures, exotic animals, and dreamlike landscapes in his travels. A swashbuckling period piece in any event, and shot in 3-D, the film has won awards for its costume and make-up design. Composer Ennis Rotthoff will be at the opening night to talk about his score.

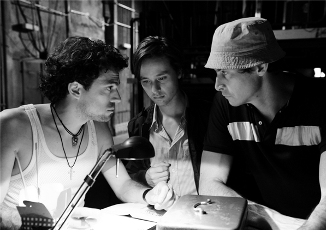

A film that has literally swept awards, including the top Lolas for German films in 2013, is newcomer Jan Ole Gerster’s low-budget first feature, his modest sleeper hit, Oh Boy.

It may seem unlikely that a slacker dramedy of Gen-Y youths would double as a valentine to Berlin, but this black-and-white beauty scored with New Orleans-style jazz knocked Tom Hanks and Halle Barry aside (in Tom Tykwer’s Cloud Atlas) to garner Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor awards for Tom Schilling (as a lazy twenty-something basking in German-style dolce far niente) and Michael Gwisdek (as a salty old barfly who manages to reflect on the past) respectively. Ironically, Gwisdek beat out his own son, nominated in the same category.

Oh Boy also picked up four other Lolas — the big ones: Best Film, Best Director, and Best Screenplay to Gerster for his seemingly non-story of a day in the life of Niko, a law school dropout who is all but unconscious of his drift into oblivion. Singer/songwriter Cherilyn MacNeil and the band The Major Minors won for their jazzy soundtrack that keeps the film moving when Niko seems to be standing still. We’ll see Niko reckon (or not) with his begrudging father, his dissatisfied girlfriend, his prying neighbor, the government, performance artists, and the mainstream theatre as well.

The grainy cinematography shot with the RED camera takes us to a Berlin at once reflective of the Nazi era (at least via the stage) and strangely out-of-history as we contemplate the metropolis from Niko’s point of view. Character and setting are in the foreground here, yet it’s sure to be a mastery of tone and style that will introduce writer-director Jan Ole Gerster to audiences of the “German Currents” as the country’s “new cinema hope.” Gerster has already been called “the voice of his generation” and Oh Boy, the film that made the mark. With the screening of his winning debut in Hollywood, Jan Ole Gerster will be on hand for discussion at the “German Currents.”

Two films in the series transport viewers to the American continent in its ruggedly majestic beauty. The Adventures of Huck Finn takes us on a raft with Huck and Jim down the mighty Mississippi. In this family flick for a Sunday “kindermatinee,” it will be interesting to see how director Hermine Huntgeburth navigates the many dialects of Mark Twain, master of wit and dark satire.

Meanwhile half a century later, Thomas Arslan takes us up from Ashcroft, the northernmost terminal of the railroad, into the wilderness of British Columbia for the Klondike Gold Rush in 1898. The only German director in the Competition section of the Berlinale this year, Arslan is known for his earlier character studies.

Even here in the vast terrain of a Canadian “western,” it may be that he defies genre expectations somewhat by keeping the frame tight on his actors, who have been highly commended in critics’ circles. Nina Hoss trades the East German countryside of Barbara for the backwoods trek to Dawson City as Emily Mayer; along the way she meets the rough-hewn cowboy Carl Boehmer, played by Slovenian actor Marko Mandic. Of course they both come with mysterious pasts that can’t help but attract them to each other, perhaps even more than the shining nuggets that promise a new life for them and their wagon of a handful of other “Dutchmen,” as they were then called.

A raspy, ne’er-do-well journalist reports ahead to a New York newspaper about these German gold diggers, who are notably missing from the repertory of the late-western sub-genre in film history as well as from documentation of the early waves of emigration in German national history. The wide-screen camerawork aims to serve the genre, while Dylan Carlson’s twangy electric guitar score might be updating the ambiance beyond its days. Arslan says that while he discovered his material in a book he found with excerpts from diaries of the Klondike days, what really drew him were the photographs of the era, a time when amateur photography was just taking off because new, small cameras allowed for lensing without a tripod. Nonetheless, how would they capture the seeming endlessness of the landscape, the horizon at which one could never quite arrive?

The camera stays abroad for Layla Fourie, Pia Marais’ noirish drama from

South Africa,

where this director and co-writer was born and came of age.

Layla, who raises her son as a single mother in Johannesburg, moves from one casual job to

another until her training with the polygraph lands her a position in a

security company with a specialty in lie detectors.

Yet a fateful accident leaves her enmeshed in a tangle of deceit, an evolving motif in the film that also encompasses the potential loss of her son. While guilt, suspicion, and paranoia cloud the air as Layla heads toward a psychological crisis, a political subtext is there for the taking, beginning with the back story. Sexual and racial tension seeps in as well, as Layla crosses a boundary with one of her interviewees.

Personal space and personal security become another leitmotif as the past haunts Layla in insidious ways.

After living in Berlin for many years in exile from apartheid and pursuing her work at the DFFB, Pia Marais looks back at her home and questions whether South Africa has truly escaped the long shadows of apartheid. Little by little, Layla Fourie emerges as a classic political thriller, taking us to a country that is still healing its wounds and seeking a way out of the fundamental fear and mistrust that are its historical legacy.

We are in the eastern interior of South Africa here, where the earth is parched and the horizon is bleak. The British Rayna Campbell and German August Diehl as leads have not sprung up from South African soil but are indicative of the world of co-productions that cinema has become. Their accents reveal their native roots, yet their acting is stunning, understated though multi-textured in response to the duplicity of their milieu. Rayna Cambell will be in attendance at the “German Currents.”

One documentary in the series, Beerland, is arguably as German as a film could be, strangely so or not, though its director, Matt Sweetwood, hails from the Midwest of the United States. He’ll be on hand to present his film.

Another outstanding documentary is More than Honey, directed by Markus Imhoof as a Swiss/German/Austrian co-production. Scooping up the 2013 Lola (German Film Award) for Best Documentary among many other kudos, Imhoof tackles the fact of the worldwide extinction of bees. His vexation sends him globe trotting from California to Switzerland, China, and Australia all the while it takes us inside both the flight and the hives of the bees to peer into their breeding and their brains alike. But it all starts in the Alps where Swiss filmmaker Imhoof stands for multiple generations of beekeepers in his own family. With good reason, he identifies with the beekeepers in his film, observes their work, and agonizes with them as they lose their colonies.

Anyone who follows the news knows about the massive impact on the global food chain that the “colony collapse disorder” of bees is causing, how their forced migration from region to region to service large-scale orchards contributes to their onset of disease and invasion by mites. The camera, operated by Jörg Jeshel and Attila Boa, takes us on an “up-close-and-personal” path as the drones tend to their queen or pollinate plants; shooting at a speed of 300 frames per second, they follow the bees zipping through the air and also at home in their hives, in more detail than we can realistically imagine.

Director-screenwriter Markus Imhoof tells us that fifty

years ago, Einstein had already warned of the symbiotic relationship binding

these pollen gatherers to us: “If bees

were to disappear from the globe,” he predicted, “mankind would only have

four years left to live.” Put another way, the economist-filmmaker in

Imhoof sums it up: “In the

struggle between bees and the neo-liberal market economy, bee brokers push

beekeepers, who respond by

pushing bees, to further increase their performance. Bees have become chain

workers, a machine expected to function upon the simple push of a button. In that sense, (assuming the risk of

sounding presumptuous), I could say that More than Honey is a bit

like Chaplin’s Modern Times — as

told by bees.”

“German Currents” October 4-7, 2013, Egyptian Theatre, 6712 Hollywood Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90028

For the full schedule, tickets, and further

information about, go to:

http://www.goethe.de/germancurrents

http://www.americancinemathequecalendar.com/content/german-currents-2013-festival-of-german-film