5-5-21

Go East, Young Man! Antonio Pisu’s Est at SEEfest

By Diane Sippl

Est, written and directed by Antonio Pisu as his second feature film, fits hand-in-glove with the concept and purpose of SEEfest (Southeast European Film Festival Los Angeles, now in its 16th edition), not just because it shows us the “East”—in particular, the “Southeast”—but because it reveals the borders, generally all too rigid, but once in a while, porous, sometimes even becoming bridges among the countries of the region. In this case, the “East” is Hungary and, primarily, Romania; the “South” is Italy in a time before it was inundated in its own “south” and “east” by refugees from further south and east, (and before it was the first European country to be entirely devastated and shut down by COVID-19 with tourists from every direction).

Of course, the flood of emigres to Italy in the last decade is not any newer than the stream of Italians to western European countries as both guest workers and potential citizens. It’s all “relative”—only a matter of geography and history, or better, economics and politics. So it’s understandable that a trio of adventurers from Cesena in Emilia-Romagna, Italy might have it in them to get it right—not the map, but the compassion—except that they are quite young, and one of them seems never even to have heard of the Berlin Wall, which is about to fall. It’s the autumn of 1989.

Bibi (Jacopo Costantini) is more worried about “girl trouble” than watching (let alone reading) the news. Rice (Lodo Guenzi) is fairly well versed in history and politics and has at least some idea of how things work in the “East,” so he’s game to try it out. Pago (Matteo Gatta), a local tour guide, knows several languages and feels he’s outgrown his native town. They’ve all been buddies since childhood, and off they go to discover the world together.

These hapless twenty-somethings leave girlfriends behind and hit the road for a mere ten-day sojourn that they can afford, if only by offering “yard sales” behind the Iron Curtain that will fund their way. They’ve packed up some of Italy’s own black market “exports” (cigarettes, chocolates, eye-popping lingerie). Who do they think will be able to afford them? They’ll find out, one way or another.

Most of the normal road movie conventions are to be found in Est: the inevitably empty gas tank, changes in plans or even destination, disrupted communication with those back home, the re-purposing of goods brought along, encounters with strangers and the uncertainty of whom to trust, and the discovery that even one of your own company can’t be relied upon to toe the line. These standard obstacles of the genre are each compounded in the midst of a dictatorship, be it local or remote, and they are more than doubled with the lack of a common language, but filmmaker Pisu keenly plays with another layer that can make matters even worse.

For all their good intentions, his “three musketeers” are incredibly naïve. Bibi’s ignorance will obviously get them into trouble; we’re on edge waiting for him to put his foot in his mouth—or a stranger’s suitcase into his car, despite the fact that all the world’s airports announce relentlessly, “Do not leave your baggage unattended or accept parcels from strangers.” So what if there’s contraband, even weapons or a bomb inside it? Pago thrives on the suspense of being in jeopardy—otherwise they could have gone to Rimini instead of Romania. He’s willing to bank on the help of one Girolamo Zorli, a Mafioso-looking compatriot from the trio’s own Emilia Romagna who buys them a round of palinka but whose shady-looking ways are ambiguous enough not to be trusted.

Rice is the only one who seems to care about Ceaucescu and secret police, yet he’s the very one to open the car trunk in the public square and peddle to passersby. This isn’t even to mention his ubiquitous video camera and his moviemaking of the daily living (or dying) reality of Romania; he’s more conspicuous than any street photographer. They panic when they think they’re being tailed on the road but never give a thought to curfews or tapped phones. They assume they are exempt from prosecution because they are foreigners, armed with a stockpile of cigarettes (even the officers at the border preferred their bottles of wine and Italian salamis). What really never occurs to the three knights-errant is that their mere presence or contact with the locals endangers the native Romanians, people they’ve hardly met, who offer them earnest if cautious hospitality.

Antonio Pisu has commented:

Like the rest of the world, Italy pretends it knows nothing about the Romanian government today, or its past. Using the film medium, that history can be retraced in the eyes of three young Italians and become universal: a metaphor for how little it takes to change one’s point of view. It’s a window on the ironic fact that what we take for granted every day is nothing more, for most of the world’s population, than a magnificent spread just glimpsed from the back row—on tiptoe.

Then how does this writer-director turn a linear road movie—linear in terms of both geography and narrative—into an indelible inner journey?

The three young pleasure seekers travel the route of a triangle for their trip, setting out from Italy due north to Budapest, Hungary; but they soon find themselves venturing further east than they had imagined, all the way to Bucharest in Romania. Yet the film follows the direction of their emotions. For that map, picture a big throbbing heart—it expands as it encounters one challenge of empathy after another, and it contracts, shrinking back in fear, as it endures the circle of the Romanian Securitate closing in on it more and more tightly. That could be because the travelers’ actions turn not only riskier, but more criminal in the eyes of the State, and also because the most naïve and inane of the trio, Bibi, increasingly leaks out too much information. He’s polite and sympathetic when the turn of events calls for political savvy, or at the very least, street smarts. Bibi’s obliviousness to the situation at-hand can be counted on from scene to scene, but so can his compassion. As the danger escalates, Pago and Rice begin to look like novice Quixotes performing gallant services for the vulnerable with Bibi as their dim-wit squire, but none of the three (save perhaps the budding accountant Rice) has a clue as to the lion’s den not marked on the map and all the life-and-death repercussions of the “accidental misbehavior” of delusional tourists in a land of dictatorship.

The central conflict arises when a stranger named Emil overhears Pago announce their itinerary in a phone call from a Budapest post office and asks him to deliver a suitcase to his wife and child in Bucharest. Rice is smart enough to deduce that the man has fled and they should stay out of his business. They say no. But the baggage ends up in their car trunk thanks to Bibi’s secret concession to the refugee. Pisu deftly employs the suitcase, its contents unknown, first as a source of mystery, then as a burden for three wayfarers out for a good time, and finally as an increasingly dark threat, or at least a “red flag” for its proposed delivery. But such a lyrical director as Pisu also draws on two other filmic strategies—the ironic juxtaposition of music and image as well as the power of song per se, not just particular songs (oozing with nostalgia as they are) but also the role of song and singers in the cultures portrayed. The charm of the film, and what makes the road trip so emotionally “moving” and its heart so expansive, is the way Pisu weaves these two stylistic devices together throughout the voyage to consciousness on the part of his three innocents.

Defend me, from opposing forces

At night, in my sleep, when I’m not conscious.

When my path becomes uncertain

And never abandon me

And never abandon me

These lyrics, sung by the composer-songwriter-singer Franco Battiato, are well known enough to be sung by almost any Italian of the time period. Just the same, his name and the title of the song, “L’ombra della luce” (“The Shadow of the Light”) are printed on the screen in English right along with all the song’s lyrics (a rare treat for those reading subtitles and those yet unfamiliar with this iconic Italian). It’s raining as our three buddies cruise through a Romanian village, and the music could be diegetic, the singer sadly crooning on the car radio—or it could be seeping from the hearts of the youths who are, essentially, tourists, and beginning to feel like it as they pass a peasant woman eating sunflower seeds on a street bench, a man driving another, whose arm is around a child in their horse-drawn cart, or a little girl watching from a field where her mother toils. The girl glares straight at the camera. These are not actors, but local dwellers. A man and a woman frowning, picking out food to eat from a bin-size bag, another couple aboard a hay wagon. A man in a wild, untrimmed sheepskin coat, holding a live goose, a woman holding a child. We expect the song to be about them. A plea for mercy, kindness. But Pisu saves that pity for the three Italian youths: throughout the first three lines of the song, Est’s camera gives us a close-up of Rice, then pans to Bibi, then to Pago, then back to Rice. Ironically, while their point of view is through the car window and the lens of the video camera, our point of view is on them. The montage of these images, the traveling shot of their road trip, turns inward through Battiato’s song, to the protagonists and us.

Bear me up to your highest peak, in your realm of peace

And never abandon me.

Battiato’s hushed voice comes to sound like a prayer for all the indifferent and self-serving who ignore the dispossessed. At that moment, the car turns around so they can look for the suitcase Rice tossed out the window when he panicked that they were being followed. The irony of Battiato’s lyrics is even more acute when the song is repeated a few scenes later as the lads find the opportunity to sell their wares. A long line of desperate customers is diverted from a near-empty store to the trunk of Pago’s car as Rice hawks cookies, chocolates, cigarettes. “Unexpected, but very nice vibes here! So bubbly!” quips Bibi. The hungry clients hand over their money.

Defend me against opposite forces.

The night, while asleep, when I’m unconscious,

When my path becomes undefined.

And never abandon me.

Please, never abandon me!

We see close-ups of Romanian faces, all types, all ages, and then of their hands, outstretched, receiving food, videotapes, clothes. And the image cuts to the videotape Rice is making, of people buying leather boots, backpacks. And handing over their money. Until another car arrives, Militia, and a scowling officer grabs the three Italian passports, then drives off. Who are the “unconscious” now? In case we managed to construe the lyrics as praise for three Good Samaritans, the next scene delivers the keynote of Est.

In a small, all-but-empty cabaret that night, they spot the missing suitcase. The singer (Iulieta Szomyi), a lady in black—with black hair, dress, jewels and black gossamer gloves, shoulder to fingertips—takes a seat at their table and steals the scene like the Wicked Witch from the East, except that she’s mesmerizingly messianic. Her dream was to sing at the Stadt Oper in Vienna, and she is indeed theatrical. The boys (now they betray themselves as morally and socially immature) earnestly offer to buy the suitcase back, offering its worth in money. “That is not a suitcase,” she soberly states. “You know what’s inside? So why did you throw it in that field? I saw what’s inside. The money you have is not enough.” She reduces them to a nonplus. “…How much would you pay for a memory? A dream? A hope?” she asks. We see rotating close-ups on each of the boy’s faces. Pago asks her what she wants. “You should have asked me this a long time ago,” she snarls. “It’s too late now. But you, what do you want? For how long will your holidays last? This is not a market.”

The scene is almost surreal, a bit like something from Dracula’s Castle they visited earlier. So when we next see Rice on the road, his thoughts floating like ether out the car window again, it’s not clear whether the soprano voice he hears singing is on the radio or in his imagination. In fact, we’re seeing the real videotape of the trip on the screen, with dates printed in the corner, 14.10.89, hollowed-out buildings and industrial trucks passing by on the misty road, a young woman driving an old woman on a flatbed wooden horse-drawn cart with tractor tires. By now we realize this is the original footage of a trip that actually happened in 1989 when three Italians made this journey and documented it. And when our protagonists do arrive and deliver the suitcase to Emil’s family, and we hear Battiato’s song again, the refrain, “Do not abandon me” takes on another meaning as a mother and child unpack sweaters, soaps, stuffed animals, bracelets with joy. Now a truly generous idea comes to the fore: Rice’s videotape can take on an entirely new value by playing it for Adra, her daughter Adina, and her mother Costelia. They can watch it and see Emil pleading with the Italian trio, begging them to bring this “happiness” to his family, in the footage Rice shot with a totally ulterior motive.

It’s by no means the end of the road here—there are more twists and turns in Est for both the Italians and the Romanians, each one authentic to the time and place, but it’s worth noting that there is more documentary footage, including TV news clips of Ceaucescu in two opposing sequences, one at the height of his power and one as he is already retreating. And with that footage there is more irony as well, also achieved in song, such as that sung spontaneously by a hostess at a separate home visit, sung from memory, as so many Romanians and Italians (and Europeans and Latin Americans) did for years to come. The song is the wildly upbeat “Felicità” performed by Al Bano and Romina Power, almost a popular anthem of the era. While its lyrics are also fully printed on the screen (alluding to nothing but the sheer “happiness” of love), they are used for grand irony the first time, with cross-cutting between suffering Romanians, savoring only their memories, and the current nightly news broadcast of Ceaucescu speaking to thousands of Party members in a theatre palace as they clap in unison. The next time that song is sung in the film, it’s a new era, one of true felicità.

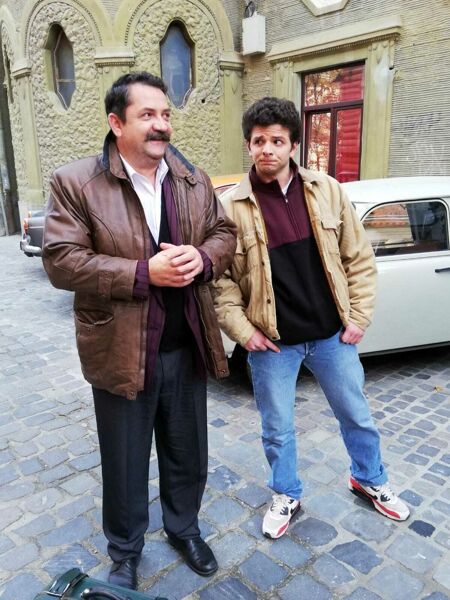

Viewers who stay glued to the screen for the end credits will be rewarded by outtakes from the original series of videotapes of the three Italians, Maurizio Paganelli (Pago), Andrea Riceputi (Rice), and Enrico Boschi (Bibi), shown sporadically throughout Est. Paganelli’s voice-over asks, “Did you picture it like this?” and we are realize that just as seeing the videotape of Emil meant the world to his family in the film, playing that same videotape for these three men, the real “actors,” now in their fifties, most likely imparted far more meaning than a treasured souvenir. Maybe our own experience via the film was equally eye-opening.

Est

Director: Antonio Pisu; Producers: Paolo Rossi Pisu, Maurizio Paganelli; Screenplay: Antonio Pisu; Cinematography: Adrian Silisteanu; Editor: Paolo Marzoni; Music: Davide Caprelli; Set Design: Paola Zamagni, Iuliana Vilsan; Costume Design: Luminita Mihai.

Cast: Lodovico Guenzi, Matteo Gatta, Jacopo Costantini, Paolo Rossi Pisu, Ana Ciontea, Ioana Flora, Liviu Cheloiu, Ivano Marescotti, Sofia Longhini, Eva Issa Popovici, Iulieta Szomyi, Beatrice Balzani, Ada Condescu, Manuela Ciucur, Dana Voicu, Radu Romaniuc, Liviu Pintileasa, Ioan Peter, Virgili Aionei, Anca Florea

Color, 104 min. In Italian and Romanian with English subtitles.