8-28-20

For the First Time—Then, and Now—in Epicentro

By Diane Sippl

Por primera vez—For the First Time

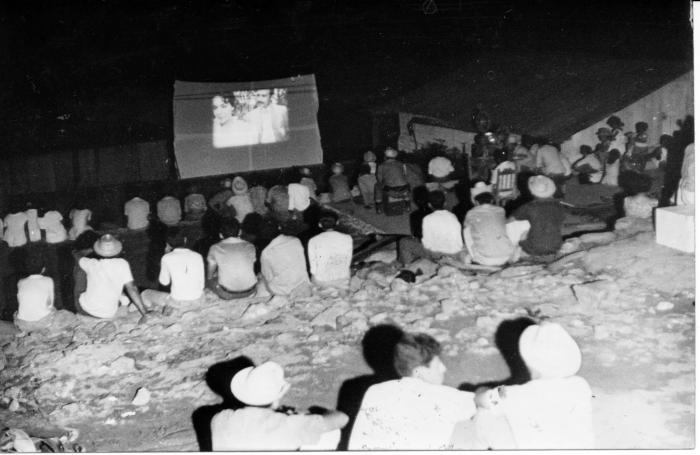

The cinema truck, with its own 2 kW electric generator and a small 16mm projector, has arrived on the rural backroads of the Guantánamo Baracoa region of Cuba. Its driver asks local villagers, “Who has never been to the cinema?

A small girl: “I don’t even know what cinema is.”

A smaller boy: “Cinema is movies...”

A man’s off-screen voice: “What is a movie, in your opinion?”

Woman: “...Maybe it’s a great group of people who have lots of important things.”

Another woman: “...there are beautiful things, beautiful girls, weddings, horses, wars... Everything!”

Another woman: “I imagine it like a party. A dance or something like that. I’d like to see one, to know what it is. Rather than just hearing about it.”

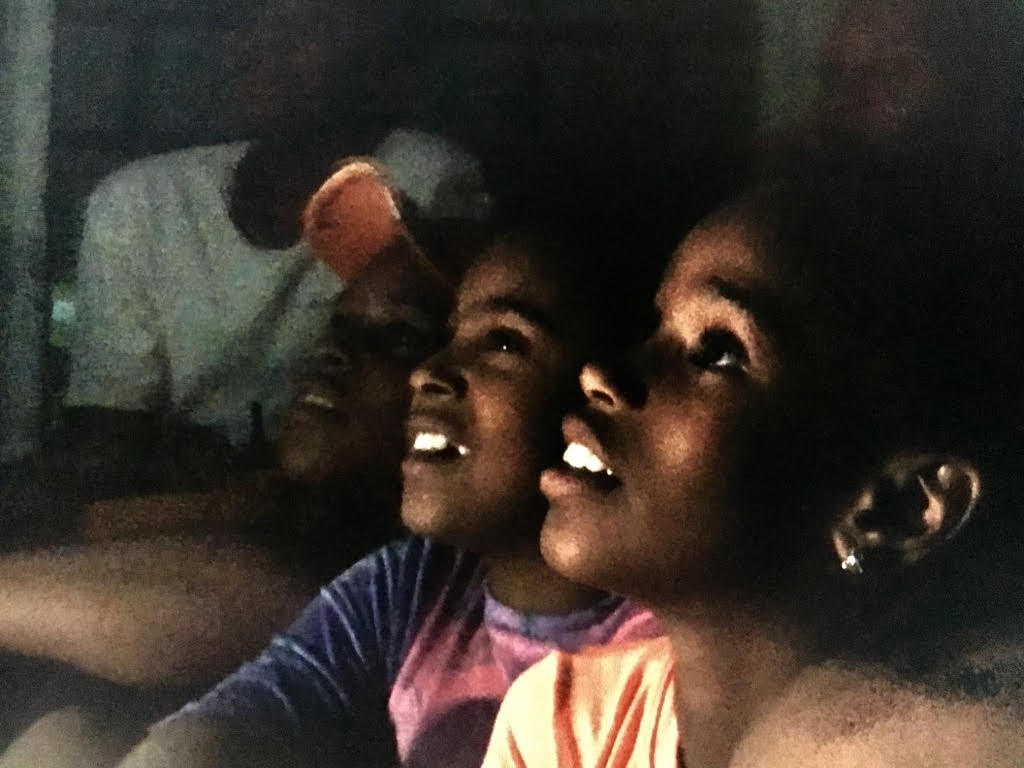

In this small valley tucked deep into the mountains, the members of farm families set up chairs together outside at night. The sky is black. The eyes of four boys shine bright as they gaze upward in wonder at a screen. Smiles spread across the pie-faces of two little girls as they point to Charlie Chaplin, installed at a revolving mechanical feeder, as he scrambles to eat corn on the cob that passes back and forth in front of him like a rotating typewriter carriage. The kernels fly. The crowd roars. Laughter fills the night air. The people hold hands, nod to each other in shared reaction, nurse babies, yawn, curl up on each other’s laps.

A first coda wraps up the film we are watching of them, Por primera vez, by telling us in voice-over, “And that is how, on April 12, 1967, in the village of Los Mulos, over a hundred people saw a movie for the first time.” After the credits, another coda arrives in voice-over, this time not from the narrator of this short documentary, but the echo of one of the women who said what she anticipated: “A movie is something very beautiful and important.”

Our own joy in witnessing the genuine, spontaneous reactions of these local viewers as they encounter a film for the first time in their lives—our pleasure in seeing each one’s surprise at the phenomenon of cinema and the ways they share their delight in the magic—is unforgettable. Most of us today might not even be able to recall our first experience with the moving image.

Yet there is something else significant about this tiny gem of a film by Octavio Cortázar: For the First Time opens with a seemingly simple question printed on the screen, “How is mobile cinema useful?” This pre-credit intertitle sets up a valid premise for viewing a film made in Cuba half a century later, Epicentro by Hubert Sauper. Tucked into his lyrical portrait of children there today is an almost hidden, taken-for-granted question: What makes filmic images—with all their capacity for illusion, and now seemingly in the hands of everyone—useful? Are there those left in our world who are making their own images “for the first time”? Then what is the value of those images?

Por segunda vez—Epicentro, 50 years later

We see what we can, what we want to see, and what is shown to us. As a nonfiction filmmaker, my task is not to “show reality as it is.” That makes no sense, it does not exist. I create a world – a movie – which consists of real people in their real environment, as themselves. They offer us their landscape of thoughts and dreams – or nightmares.

Hubert Sauper

In a pre-credit sequence over a black screen before any images arrive, Hubert Sauper takes us back long before Cortázar’s short film was made—in fact, before “the movies” took over the world: “Imagine yourself over a hundred years ago when most things that defined our modern life were invented—the light bulb, telephone, automobiles, plastic, electric chairs, machine guns, machines to fly, machines to make images move—cinema.” He then takes us to the 1898 explosion of the U.S.S. Maine off a small tropical island, Cuba, where the American flag was planted overseas for the first time. The film opens with a galactic spectacle of lights, and he asks us if we can see Cuba. Of course, we say to ourselves, “No.” “You missed it,” he tells us, “because what your eyes follow is the bright heat and the power of empire—of images and imagination.”

In the empty foyer of the American Theater in Havana, a dapper man in a black suit stands on a map of the Americas on a tile floor and points to Cuba at the center. “We are small but powerful in body, heart, and soul,” he tells the narrator, who has asked him, “What are you doing?” “Working,” says the man. He answers more than once: “Working...” It’s a dreamy way to introduce the thesis of the film, that Cuba was discovered as a “utopia” and was at the same time the epicenter of three dystopian chapters of history: “the slave trade, colonization, and globalization of power—ingredients of modern empire.” Another metaphor then comes more explicitly to life when a tiny girl in a red dress toddles on top of a yard’s walls, each one a bit higher, to reach some boys to play with, only for them to race down the street away from her. She calls to them, chases them, loses them, and turns to sit on the wall and cry, “Nobody loves me!” Her heartbreaking image, in the shadow of the lofty term, “empire,” launches both the themes and the means of the film: the expressions of real children of Havana today and their candid and savvy perspectives of the world that has abandoned them—or worse, threatens to return and capitalize on their “utopia.”

Earlier in that scene, the motif of an old man smoking a cigar, framed by waves erupting like volcanos as they smash against a sea wall, also introduces a poetic mode for Epicentro, so we don’t start out looking for a talking-heads documentary, a statistically-grounded survey, a linear news story. What we discover is observational and participatory cinema—layers of it that dovetail as textured streams of life just as the main themes overlap and interface with each other. Compilations of historical footage enter the film, but hardly as mere reportage or entertainment. This is not a showcase of Havana history; Epicentro declares what is often overlooked in non-fiction films: a consciously crafted point of view, a thesis that paves the way for an intimate look at how others, in this case, residents of this famed island, have enacted their own perspectives, transparent enough to a trained eye but resisted by outsiders, for seeing and making images. The selection and editing of scenes might feel intuitive—to some viewers unstructured and even random—yet the lyrical mode and mind of the filmmaker allow his vision all the more complexity for letting the film ebb and flow, sometimes quietly and sometimes dramatically, just as the Caribbean waves arrive on Cuba’s shore.

Cinema Is Witchcraft!

Epicentro is also quite self-reflexive, not just in the sense of Hubert Sauper’s own childhood impressions that he shares in a discussion of tourism, but from the very start of the film, through the reflexivity of the medium looking at and interrogating itself. Boys and girls sit cross-legged on the floor enthralled by The Kiss—the first to be projected—in 1896, but they laugh at people who run away from an approaching train on the screen; and at footage from 1898 of American cowboys who conquered the Wild West and then come to defeat Spain and liberate Cuba, the children cry out, “No! It’s a lie! It’s all lies....” “Mentira!” they shout when their Méliès-like Master of Ceremonies in a top-hat, who has already shown them the magic of A Trip to the Moon in 1902, proceeds with footage of “Spain’s” explosion of the U.S.S. Maine and even “gun-shot executions.” Our screen shows us U.S. cameramen with cranks photographing the “true-life documentary.” How could they not be shot themselves?

The children learn not only the lies of history but also the lies of cinema, that the footage of the Maine’s explosion was fabricated in a bath tub floating a model toy boat and cigar smoke puffed over the water. They are hardly the naïve media viewers in For the First Time. In fact, when our screen shows us their own filming process as they themselves stage battles at sea in the Spanish-American War, Sauper shoots right through the creation of early movie myths that were sold as headline stories to Americans in 1898 for the cheap price of a-penny-a-paper and the higher price of fake news and a deceitful national history, a burden to this day.

To dramatize the impact such lies have on the children, Epicentro focuses on the sub-teen Annielys as she delineates the pretext of the U.S. Platt Amendment with eloquent accuracy. “Article III was key—it allowed Americans to come and go in Cuba as they pleased; Article VII said we have to give up our naval bases... still illegally occupied....” Her vocabulary, her logic, her litany of facts, and her interpretation surpass that of many a twenty-year-old American. “That was something very cruel,” she says, “but against which one can fight.”

How would one do that? Not only does the late Juan Padron explain to us his research on the topic and his way of drawing Teddy Roosevelt, who invented himself after Buffalo Bill and his circus show, but he also demonstrates the animation process, which we later see implemented in a less sophisticated way by the children, with the director’s cell phone. Leonelis shows Sauper how she shoots and changes the speed of the camera as her sidekick imitates Charlie Chaplin’s walk, or as she struts in slow motion à la Beyoncé. She and Annielys dress up for a serious fashion photo shoot on the street in which they photograph each other.

Several points are made in the film by these lessons for critiquing and making images. We see that these “little prophets” (as Sauper calls them) learn eagerly and swiftly, but we can also note that the mentoring of their discoveries forms a pattern in the structure of Epicentro—a focal point, at that. Those adults who have something to offer the children, and who actually contribute it, make an impression; they fit into the cultural landscape of a resilient people and have a place in that society. They are not there to be serviced, but to be of service.

Work

Moving images don’t reflect history today, they ARE history. What counts is not “what happened in history,” but how it is remembered on film. Cinema is much more than memory: it is prophecy... a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy. Moving images “program” our minds, and our future, so that should make us think twice about what we put on screens.

Hubert Sauper

Out of nowhere, a large, older blond man takes into his arms a beautiful woman, but in a very precise way—they do a tango together. Later we see Leonelis doing dance exercises in a gym, first at the bar and then on the floor. She is joined by dozens of other girls of mixed ages and shapes who follow their instructor in silence. “Precise, strict, and absolutely correct, an outstanding artistic education for ballet,” comments the man who did the tango as he observes their training. He’s from Europe, and as a guest, he demonstrates his own step for the children. “Come back whenever you want,” says their teacher. The kids are yours.”

Another European who is a role model for the young girls is Oona Castilla Chaplin, the Spanish-British actress who is the daughter of Geraldine Chaplin, granddaughter of Charlie Chaplin, and the great-granddaughter of Eugene O’Neill. Several times in the film she sings Cuban songs as she plays her ukulele; three of the girls have lunch on her porch and dance flamenco. Leonelis, in particular, aspires to act in telenovelas when she grows up. We catch this little girl at home, where Oona is her mother, in a nasty fight with her about doing her homework. They slap each other and exchange foul words. It’s high drama. Then we are relieved to see that it was a test—an acting test. She asks Leonelis to make up a story—a conflict—but not a real one, because that could really hurt someone. But if people can’t tell that it’s not real (as we couldn’t), “then that’s acting.”

We never stop to think about it, but filmmaking, history, photography, dancing, singing, acting are all talents we see these children strive to achieve. Epicentro never says it; the film simply shows it. Each mentor has a purpose—to share his or her work, and to let the children find out what it feels like to do that work. Along the way, the film also shows us many kinds of tourists, past and present, and their ways of consuming song, dance, photography, and yes, even cinema, beginning with the earliest Americans themselves. Thankfully, among them are those independent artists who, early on, took cinema into their own hands before it became “industrial” and “imperialist.” The end of the film lets the children see scenes from The Gold Rush and The Great Dictator. Charlie Chaplin, as Hitler, spins the world on his fingertip—even bounces this balloon globe off his butt—until the bubble bursts. There is a roar of delight that takes us back to the laughter at his corn-eating scene in Modern Times—in For the First Time.

Utopia

Some people dream about “making Cuba great again.” A famous American real estate tycoon has long planned a tower with his name on it. It’s the “T-word.” I don’t want to spell it.

Hubert Sauper

In many ways, tourists are today’s invaders of Cuba. They are there for themselves and take up the spaces, physical and social, to which the residents of the island have no access. Showing off the talents and the pluck of his film’s participants, Sauper grants them “come-uppance capers” that almost parody the old adage of finding compassion by “walking in the other’s shoes.” The girls ride like princesses in the bicycle rickshaw down the Malecón. Feña’s dream has been to float down the avenue in a vintage pink American convertible, and she does. Leonelis and her little beau are carried along by a horse-drawn cart, and Hubert Sauper even smuggles them into the Iberostar Parque Central Hotel to swim in the rooftop pool and gorge themselves on ten-dollar pastries on the poolside deck. It’s all like a demand for due respect, somehow related to the demand for the freedom to “move, to know, to love, and to aspire” (as W.E.B. Du Bois put it in his 1909 biography, John Brown), here at eye-level, on the street, in Havana.

Feña doles out a superficial response to the supercilious attitudes tourists express. When they ask her how she feels when she notices that those outside Cuba have “more,” she retorts, “Happiness—what is it? Drinks and salsa!” They laugh at her. The joke’s on them. Later in the film she tells Sauper exactly what she thinks of the current American administration and, for that matter, Cuba before the revolution when tourists wanted Havana to provide them with night clubs and prostitution, casinos and cocaine, and Habaneros hadn’t yet taken stock of the far-off activity in the mountains. Unlike the Cuban man who closes his door when he sees a tourist peering into his dwelling with a sophisticated lens, Feña tells the filmmaker, “Mi casa es tu casa” and opens the door to show him her washing machine from Russia, her electric fan from the U.S., and her refrigerator from Venezuela (“that was ideology,” she says). She holds her baby girl, who grabs her breast for milk. “That’s paradise,” the filmmaker tells the mother.

So what is paradise, or the so-called “utopia” that was born with imperialism? Bright and disciplined black children possessed with self-knowledge and self-esteem? A place where people are free to learn, build, and aspire, unhampered by racism and brutality? An island of independence and dignity won by hard work and resilience? Or are these false ideals in the face of money, consumer goods, and competition for education and work, housing and health?

What will be next for Cubans to face? Will the tides roll in further and harder? Trump brags of planting the American flag on Mars this time. Will he manage to plant a hotel in Cuba before then? Epicentro saw its theatrical opening in the U.S. the morning after the 2020 Republican National Convention (dubbed the President’s National Convention) closed on the White House lawn. Mask-less as that rally was, Mark Twain’s remark, quoted in Sauper’s film, rings loud and clear: “It’s easier to fool people than it is to persuade them that they have been fooled.” Epicentro bravely and beautifully does its part in the tall order of work to be done.

Epicentro

Director/screenwriter/cinematographer: Hubert Sauper, based on the book Energie und Utopie by Johannes Schmidl; Producers: Martin Marquet, Daniel Marquet, Gabriele Kranzelbinder, Paolo Calamita; Editors: Yves Deschamps, Hubert Sauper; Sound Designer: Karim Weth; Music: Zsuzsanna Varkonyi, Maximilian ‘Twig’ Turnbull.

Cast: Hubert Sauper, Oona Castilla Chaplin, Leonelis Arango Salas, Annielys Pelladito Zaldivar, Yorlenis David de la Cruz Leyva, Clarita Sanchez, Feña LeChuck, Juan Padron, Felix Beaton, Menale Kaza, Hans Helmut Ludwig, Deneli Beatriz de la Cruz, Leiva Yailen, Leiva Ortiz, Kirenia Sanchez.

Color, 109 minutes, in Spanish and English with English subtitles.