12-25-22

Donkey Eyes: Skolimowski’s EO Sees It All

By Diane Sippl

…But what is a “human” emotion? When someone says you can’t attribute human emotions to animals, they forget the key leveling detail: humans are animals. Human sensations are animal sensations. Inherited sensations, using inherited nervous systems…. All of the emotions that we know of just happen to be emotions that humans feel. So, simply deciding that other animals can’t have any emotions that humans feel is a cheap way to get a monopoly on all of the world’s feelings and motivation. People who’ve systematically watched or known animals realize the absurdity of this. But many others still don’t.

Carl Safina

The dilemma remains how to get an accurate understanding of the animals’ nature and (if appropriate) emotions, without imposing on them assumptions born of a distinctly human understanding of the world.

Caitrin Nicol

… it’s quite obvious that this film was made out of love—for animals and nature.

Jerzy Skolimowski

Creatures Large and Small

In her 2013 book, Animal Wise: The Thoughts and Emotions of Our Fellow Creatures, Virginia Morell tells us that in the 19th century, Romanian anatomist Constantin von Economo identified spindle-shaped neurons in the human brain as the cells that “make us human” because they’re connected to our feelings of empathy, love, sociality, and emotional suffering. By 2007 John Allman discovered in the brains of other animals the same cells, arguing that they would be particularly useful for an animal living in a complex society—one in which making accurate, intuitive decisions about the body behavior or facial or vocal expressions of another is crucial for survival. Yet by 2015 Carl Safina noted that, for too long a time, making “even the most informed, insightful, logical inferences about other animals’ motivations, emotions, and awareness could wreck your professional prospects” as a scientist.

In his essay, “Big Love: The Emotional Lives of Elephants,” Safina poses the ultimate question: “what ‘distinctly human understanding’ hampers our understanding of other animals’ emotions? Is it our sense of pleasure, pain, hunger, frustration, self-preservation, defense, parental protection?” He suggests that it is human shortcomings that prevent us from recognizing the full range of emotions in other animals—not just satisfaction of bodily needs but feelings of joy and sadness, of belonging and loss. Put another way, might it be that a sharper grasp of human emotions could put us closer in touch with the emotions of other animals? This tandem task is a delicate balancing act, always at risk of anthropomorphism, especially in the hands of literary and visual artists when scientists hold us back. Another question: is our Big Love of other creatures an obstacle for objective study or a subjective tool for approaching the dilemma? In fact, it was as an animal lover that poet, painter, dramatist and filmmaker Jerzy Skolimowski was most galvanized to probe the difference between directing humans and working with other animals to create his latest work of art.

Motivating the Camera

Whoever taught children that the sound a donkey makes is “hee-haw” got it a little bit wrong; it’s “e-o,” as in EO, the film aptly named for its protagonist who’s also the one telling the story—that is, assuming it’s not necessary or even adequate to put tales into words. EO’s sensibility is mainly visual, auditory, and tactile; he is as acutely perceptive as he is quietly responsive, sniffing out both trouble and opportunity almost before they arise. Without notice, his perspective becomes ours and we find ourselves inhabiting a landscape where linear trails, tracks, and destinations make less sense than free reign; that is, plotted story arcs fall by the wayside in an instinctive world, one not only of survival but also of memories, dreams, and desires.

There is an old, seldom spoken rule for the arts and crafts: form follows function. If you want a film about an animal to generate emotion, how do you create it as an animal feels it? Au hazard Balthazar managed this feat in 1966, to the point that this milestone in cinema history by Robert Bresson brought on a lifetime of drive and commitment for a young Polish cineaste. In a sense, Balthazar is the ancestor of Skolimowski’s character, and the story of the new donkey’s genesis is one worth sharing today as EO, already winner of the Cannes Jury Prize and named Best International Film by the New York Film Critics Circle and Best Foreign-Language Film by the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, heads for the Oscars as Poland’s submission.

In a climate of Hollywood block-busters such as Avatar: The Way of Water and Top Gun: Maverick, the most exquisite big-screen experience of 2022 is an encounter with the enigmatic, episodic ventures of a humble donkey in a film as idiosyncratic as its maker. The 84-year-old writer-director-producer Jerzy Skolimowski has worn many career hats: a one-time boxer, he has also worked as an art designer and even more important, as an actor in his home country, Poland, and abroad. His previous films as an auteur (The Shout, Deep End, Moonlighting, Essential Killing) have increasingly experimented with artistic form, yet in a sense, this master of cinematic language has been living with EO his entire adult life, and it is his urgent pleasure to tell us why. With his co-writer, co-producer, and wife, Ewa Piaskowska, he shared his story at Laemmle’s Royal Theater in West Los Angeles in early December.

Fresh Out of Film School

“When I finished studying at the film school in Łódź in Poland, it was 1966 and I wasn’t even thirty years old, but I had a chance to make my first professional film, called Walkover, that summer. It was screened in maybe twenty cinemas all around Poland and one cinema in France, because some crazy French guy had seen it in my country. Toward the end of that year, I received a phone call from Paris. It was from Cahiers du cinéma, which, then run by people like Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, had already been established as the leading film magazine in the world. The secretary on the phone said they wanted to interview me. I thought it was a bad joke and asked why, when I was just out of film school and had made only one film.

“No, no” was the answer, “it’s not a mistake—we just had a session with all the editors to make a list of the ten best films of 1966, and your Walkover took the second place.” After a long silence on my side, I recovered my voice and asked, “Who took the first place?” The answer was “Au hasard Balthazar by Robert Bresson.”

I asked to postpone the interview for a day or two so that I could see that film and make some kind of comparison or comment. They agreed, so I ran immediately to the cinema, purchased a ticket, and viewed the film. By that time, I’d already developed a kind of semi-professional, semi-cynical attitude toward the film I was watching because I was more interested in finding the answers to why the camera was put at one angle, not another, or why a tracking shot was used instead of a steady camera. I wasn’t interested, really, in getting emotional about the story I was watching or getting involved in the plot.

But at the end of the film there is this famous scene when Balthazar, the donkey, is dying, lying on the slope of grass, surrounded by a herd of sheep, and all those sheep have little bells around their necks—“ding-a-ling,” delicately—but there were several dozens of those sheep. It was like music for a funeral—an incredible scene. And when the light went on after the screening, I was so surprised to learn that I was crying. I had tears running down my cheeks—the only time it would ever happen. Never before and never after that.

An Homage to Bresson

I understood that I’d received a great lesson from the old master. The lesson was—I’ll try to put it into words—that the animal character can move the audience stronger than any professional actor who would be executing his brilliant craft, declaiming some fantastic words—I don’t know, Shakespeare, or whoever it might be. We could be observing something really phenomenal, like the best performance, but still in the back of our minds there would be this disturbing knowledge that just after what we were watching, at that moment, the director would say, “Cut!” and the actor would jump up and go for a drink or make jokes with his colleagues, and therefore, emotionally speaking, we would be kind of cheated, slightly.

But when the animal is dying, animals don’t know what acting is, they don’t understand the process of acting, they are just “them,” so I took the death of Balthazar as if it really happened, and this is why I cried. And this is why we were thinking about making the film with the animal character as the leading character. Obviously, the donkey—and the remembrance of my tears, of course—took a very important part in that decision.”

The EO Way

When Skolimowski was asked how he directed not one, but six donkeys for EO, his first answer, “Basically, it’s a lot of carrots,” was not as glib as it sounds. Nor was his next response: “But they’re all playing the same part, so it’s a bit easier than directing six actors.” He then delved into the exceptional beauty of the gray Sardinian donkey, and his desire to bond with the animal became clear. Spending all his free time with EO allowed the filmmaker to become an effective donkey whisperer, and this affection enabled a vital exchange with the animal that led Skolimowski to discover something remarkable on the set: EO’s point of view was more enticing than the standard master shot at each location. The animal’s perspective mysteriously endowed the film with a new authenticity that was at the same time a wondrous take on the natural world.

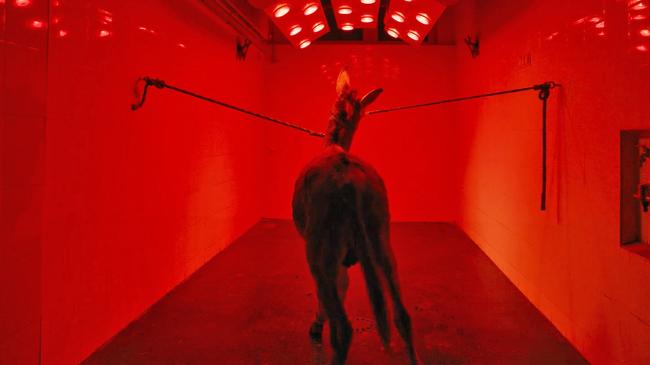

We meet EO at a circus shortly before its tent is torn down and he is at once released and abandoned by his admiring trainer, Kasandra (Sandra Drzymalska). Thus betrayed, his new travails begin. Alone and independent, he traverses forests and fields, mountain tunnels and streams, though he is sometimes corralled or bridled for labor. His wide eyes reflect a mutual sensitivity with other creatures large and small—camels groaning, wild horses running freely, a dog on a leash barking ferociously, an owl surveying the scene from above, wolves hunted via laser beams, foxes caged up on a fur farm, a bird lacerated by a windmill, fish in a shop window aquarium, cows prodded through a maze to be slaughtered.

EO delivers us to Polish politicians speechifying the same old blabber to inaugurate a horse stable as a priest blesses it. School children play with him in a pasture, learning to show their affection. Inadvertently, he distracts a player from his penalty kick at a village soccer game and ends up the mascot of the winning team, much to his dismay and his demise. Beaten half to death by the losers, he struggles to resurrect himself in his surreal point of view as an insect-like robot whose every bone and joint fights for strength and flexibility once again.

The humans who inhabit EO’s world are rarely compassionate, but one, an empathetic young priest (Lorenzo Zurzolo), frees him from captivity and jokes, affectionately, that the salami he offers EO might be made of donkey meat! This rare companion takes him to Italy after the man has lost his lot (a villa home) in gambling and is soon to lose his stepmother lover (Isabelle Huppert) as well. It’s as if EO quivers over their plate-smashing quarrel as a bystander nibbling the villa’s grass, yet another scene finds the donkey poised on a narrow bridge over the tumultuous waters of an enormous hydro-electric dam. The gaze into the rushing depths looks like a temptation for suicide.

The Cinema Way

As a director, Skolimowski employs every aspect of cinema as an art form,adding some new dimensions as well. Kuleshov’s early but fundamental theory of associative editing fuses objects and sounds with expectations and fears. Frames of bursting color intercut with black screens, bold hues edged or laced with dark shadows, whole scenes saturated with flickering red filters—all of these painterly strokes lend an expressionistic, surreal sense to the film that announces itself as EO’s experience so that when off-screen music resounds, such as the thundering chords of Beethoven, all belongs to the same world. Human dialogue, whether Polish, English, French, or Italian, is so minimal that it’s as if only the tone matters, that being what EO can perceive. And yet EO himself is an unforgettable sight for us to behold in extreme close-ups of his eyes—wide, dark, and intense but ringed with white hair, their natural highlight. The camera lets us see a tear. Do donkeys cry? We do believe so.

EO is a surprise, from one moment to the next. Owing to Skolimowski’s gifts—as an artist, a poet, a director who has been an actor and an animal lover with the same vitality—we are able to feel the life of a donkey as a donkey might feel the lives of humans. It doesn’t take words to tell this story. It takes heart.

EO

Producers: Jerzy Skolimowski, Ewa Piaskowska; Director: Jerzy Skolimowski; Screenplay: Ewa Piaskowska, Jerzy Skolimowski; Cinematography: Michal Dymek; Editing: Agnieszka Glinska; Music: Pawel Mykietyn; Sound: Radoslaw Ochnio; Production Design: Miroslaw Koncewicz; Costumes: Katarzyna Lewinska.

Cast: Donkeys Hola, Tako, Marietta, Ettore, Rocco, and Mela; Actors Sandra Drzymalska, Isabelle Huppert, Lorenzo Zurzolo, Mateusz Kosciukiewicz, Tomasz Organek, Mateusz Kosciukiewicz, Lolita Chammah.

86 min., Color. In Polish, Italian, English, French with English subtitles.