10-12-15

Afia Nathaniel’s Dukhtar: In the Name of the Daughter

By Diane Sippl

Set today in the northern mountains of Pakistan, Dukhtar is an intense road film of a mother and daughter fleeing a traditional practice of marrying off child brides. “Dukhtar” means “daughter” in Urdu. The mother, Allah Rakhi (“God protects”), who suffered this same fate, now sees her much older husband, Daulat Khan, a powerful tribal leader, using ten-year-old Zainab as a bargaining chip in an endless blood feud with the neighboring clan. A moment arises when the woman and girl can flee, and they escape in the mountains until they are picked up by a truck driver, Sohail, who is heading south, even if not all the way to Lahore, where Allah Rakhi could find her mother. As an ex-muhajid, Sohail knows the heated politics of the area and can help his stowaways, but he himself is on the run.

Shot in the Hunza Valley and remote regions of the Punjab, in an area of political unrest where no independent feature film has ever been made, Dukhtar presented many obstacles for its filmmaker. Working with 200 extras and filming chase scenes at the world’s highest altitudes wasn’t easy. The physical location of isolated mountain terrain and desert plays a main role in the film. But there were plenty of other hurdles in bringing the film to fruition. I met Afia Nathaniel on the occasion of Dukhtar’s submission as Pakistan’s entry for Best Foreign-Language Film at the 87th Academy Awards, and I interviewed her in West Hollywood.

Dukhtar opens its theatrical release in the United States on October 9th to coincide with a special day. On December 19, 2011, the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution 66/170 to declare October 11th as the International Day of the Girl Child, to recognize girls’ rights and the unique challenges girls face around the world.

KINOCaviar Can you talk about what you faced in making Dukhtar?

Afia Nathaniel When I was in film school in New York, I never believed it could be so difficult to make a film, but in a developing country, it can be even harder. Dukhtar was a story with two female leads — two brown women — played by two unknown actors. And then I was a brown female filmmaker making my first feature film, so no one knew of me. It was being made in Pakistan, a country not known for cinema and where there is hardly a film industry at all. I didn’t subscribe to Bollywood or the accepted genres of the region, so there were no stars in my film, and there was no white male lead or familiar traditional hero. And then there would be subtitles. It was a ten-year struggle to find production money, and it finally came from Europe.

KC How much independent filmmaking is actually done in Pakistan?

AN In 1947, the birth of Pakistan, when it inherited the Bollywood tradition for cinema, it came to be called Lollywood (B is for Bombay; L is for Lahore). The most popular are masala films. Only now, in the last ten years, has Pakistani cinema got the courage to find a voice. Lollywood is big but with regional languages, so to make a film in the industry, you have to stand your ground and take a risk.

I wrote, directed, produced, and co-edited Dukhtar, so I feel I have found my feet within the industry. The film’s release ran four weeks straight within the country, which is unheard of for an art house film competing with Hollywood and Lollywood offerings.

KC How did the shooting process go?

AN For much of the time I was the only woman surrounded by a crew of 40 men on my set, in this barren region of dispute between Pakistan and India in the middle of winter. Below-freezing weather along with sectarian tensions kept me on my toes. There were cases of bomb blasts, and security was deteriorating. I had to be open to all the elements, which kept shifting — the light with the landscape, the weather and the opportunities for capturing it within the frame. Remember, this was a road trip. We had to cover great distances yet finish filming in four weeks to make it back to Lahore before the snowfall blocked our only passage, the Karakorum Highway.

KC And post-production?

AN It took almost a year to edit because I had to keep trying to raise funds.

KC Do most of the people in the region of the film speak Pashto — or Punjabi?

AN While Allah Rakhi’s tribal culture is Pashtun, Urdu is the national language. Almost everyone understands spoken Urdu, so even though the story is set in a location with its own dialect, I created a character with a context for using Urdu. The women there are forced to spend their lives within the four walls of the house. Their only exposure to the outside world is through television. Women really watch TV, soap operas, and it’s how they pick up Urdu. I heard women in our location speaking flawless Urdu — it’s a way of exposing them to culture.

KC What in particular inspired your writing?

AN I read a news story about a woman from a tribal area who actually kidnapped her two girls to prevent them from becoming child brides. I couldn’t get the image out of my head. An illiterate woman in a small village in such a deeply conservative region — where did she get the courage? That’s how Dukhtar started, a mother and daughter on the run.

The statistics are staggering. In Pakistan one out of every five girls under 18 years of age is married off already as a child bride. And it’s not just there. Across the world, over 15 million girls every year lose their childhood to marriage. We need to speak about this issue. The film has made it more visible in the media. Liberals and conservatives alike have seen Dukhtar. A new law has been passed in Pakistan that has raised the legal age for girls to marry from 16 to 18 years old. That’s progress.

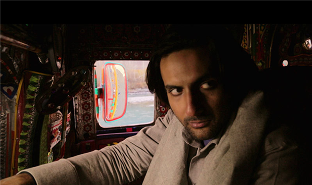

KC When the trucker gives a lift to Allah Rakhi and her daughter, we fear for them — for one reason, because his truck is so big and loud. With its spangles, it literally glitters and glows, and it really stands out in such a stark landscape. I can see that its many hues make for a very cinematic image, but is it realistic?

AN The truck drivers in Pakistan tend to have very colorful personalities, and they use their trucks to represent themselves, so they put a lot of love into decorating them quite artfully, as a statement. Sohail’s truck might look garish, but he has inscribed it with romantic poetry written on the sides of it.

Sohail was a mujahid and he defected from the war. I based him on a real person. We generally hear the same old story, of men and boys who enlist for training camps but then are used just for the war, but Sohail chose to leave war behind in pursuit of something else — love. I wanted to show this, visually.

And of course once he takes this escaped mother and daughter as passengers, hiding them as he does, he’s fleeing not only his own past, but their’s as well, and becoming an “accomplice” in their crime. A war defector traveling with a married woman and her kidnapped daughter!

KC Does your own mother inspire your filmmaking?

AN My mother was always a very strong woman. I grew up in a middle-class matriarchy, including both my grandmothers. Nonetheless as a girl in Lahore I lived with the constant fear that if I stepped out of the house alone, someone would harass me on the street or kidnap me or worse, rape me because I was easy prey. But I’ve observed so many women who really fight in behalf of their children, and their conviction and spirit move me. I’m grateful to the family that raised me and to my own family, my husband and my eight-year-old daughter, born after I started making this film, for their support.

Afia Nathaniel

Dukhtar

Director: Afia Nathaniel; Producers: Afia Nathaniel, Muhammad Khalid Ali; Screenplay: Afia Nathaniel; Cinematographer: Armughan Hassan; Editor: Armughan Hassan, Afia Nathaniel; Music: Peter Nashel, Sahir Ali Bagga; Production/Costume Designer: Nauman Kashif; Sound Designer: Eli Cohn; Sound: G.M. Chaand.

Cast: Samiya Mumtaz, Mohib Mirza, Salefa Aref, Asif Jhan, Ajab Gul, Samina Ahmed, Adnan Shah Tipu, Abdullah Jan, Omair Rana, Zeeshan Shafa.

Color, HD, 93 min. In Urdu and Pashto with English subtitles.