5-1-20

Bridging the Gap: Crescendo in Our Time

By Diane Sippl

Music is a metaphor for life, in the sense that music is in a constant state of becoming,

it is making connections, between sounds, with things that are ephemeral.

Daniel Barenboim

These days when live music concerts are off-limits, it might seem that one obvious reason to look at—and listen to—Crescendo, the new German film by Dror Zahavi, is to enjoy the performances of the classical repertory. Bach, Pachelbel, Dvorak, and Vivaldi are all there, as well as a surprise at the end. Yet maybe it’s even more worthwhile to discover how standard works by these revered composers emerge from a seemingly impossible co-mingling of energies—those of young musicians, each of them either Palestinian or Israeli, recruited precisely to play in concert with each other.

For reasons disclosed well into the film, Karin de Fries, officer of the Foundation for Effective Altruism under the banner of the European Union, commissions Frankfurt music professor Eduard Sporck, a retired conductor, to form an orchestra to perform as part of the fringe events of new peace negotiations in the Middle East. The event should lead to the opening of a music school in the West Bank, the first of its kind. Professor Sporck reluctantly accepts her challenge, and upon arriving in Tel Aviv, he manages to find not the “hundred, who will generate a thousand” of such young talents, but hardly twenty.

There is no shortage of Israeli applicants, and when a relatively seasoned violinist with braggadocio to spare offers to bring in his cronies, a chamber ensemble from Tel Aviv who can look like Arabs but play like Jews and cover the quota, we find out some of the reasons why so few Palestinians have appeared. They can be lacking a musical parent or relative to teach them, or the time to practice when their work supports their families. Or, as is the case on the day of the audition, they can be blocked at the border. A violin case can look like a weapon, and as one determined 24-year-old daughter responds to her father, “It is.” What is she fighting for? Respect. For her music, herself, and her country.

Usually the only Israeli they see is an Israeli soldier.

Daniel Barenboim speaking of Palestinian youths

I think when he was growing up in Israel he never met a Palestinian,

they may as well have been on the moon.

Edward Saïd speaking of Daniel Barenboim

Crescendo might seem to give more than a nod to conductor Daniel Barenboim who, through his historic youth orchestra formed in 1999, sought to bring together the same two constituencies of emerging talent—Israeli and Middle Eastern—as he worked with music theorist and literary scholar Edward Saïd to show how music can create bonds that transcend—or better, change—politics. The film initially looks like the story of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra. But let’s remember, Barenboim was born in Buenos Aires, and his family moved (briefly) to Austria, in the mid-1950s, and not from that region as the war ended. They lived in Israel, where he was a citizen, but he subsequently gained citizenship from Palestine as well, the first Israeli to do so.

So while Crescendo speaks generally for many youth orchestras bringing Jewish and Arabic musicians together, it also follows its own beat, that of a motley group of teenagers who mostly have only music to tie them to those on the other side of the checkpoint. That border is dramatized from the Palestinian point of view. Young Omar’s father, his teacher and the other half of his duo as they perform at weddings, proudly escorts him to the audition until, that is, he is not allowed to pass the border to deliver Omar safely from the West Bank to Tel Aviv. We see Layla, a few years older and from the same community, practicing her violin with a vengeance in her apartment in Qalqilya above street skirmishes between the Israel Defense Forces and Palestinian protestors. She presses a halved onion to her nose to curb the effects of the tear gas wafting up as she plays. Her mother, strong and defiant like Layla, would hold her back from an orchestra formed in Israel, a nation that has killed her relatives, but Layla’s father pushes her to compete, just as Omar’s dad urges her to look after his son.

The audition yields at least one unfortunate contestant, an Israeli prima donna who refuses to suffer rejection and vainly flaunts her certainty that she plays with more talent than any Palestinian, throwing a fit across the auditorium. Passed up for the ensemble, she will cause trouble in the end, even if inadvertently. More pervasively disturbing is the gifted Israeli violinist, Ron, haughty as an individual and as a nationalist, who believes it’s obvious that Palestinians have no aptitude for music, that he is the best of the Israeli pack, and that it is incumbent upon him to become concertmaster. Maestro Sporck has other plans and chooses Layla, also rejecting the Israeli would-be “stand-ins,” a double affront to Ron that does more than ruffle his feathers. With no resistance, he organizes a campaign against the Palestinian musicians, especially Layla (a female, to boot, who has half as many years of violin study as Ron has), and the battle rages on, entirely at cross-purposes with the goals of this one-time “Peace Concert.”

An enemy is someone’s story you haven’t heard.

Eduard Sporck

It looks as though the effort has no way of succeeding in Tel Aviv, where animosity among the musicians finds continual fuel. Sporck relocates them to a pastoral setting in the South Tyrol, where they will not only rehearse everyday but live together, tucked away into the Alpine countryside. The South Tyrol has itself been a region historically disputed and contested between Austrians and Italians, and when Germany occupied it during World War II, it demanded that the locals choose between Hitler’s Nazis and Mussolini’s Fascists. Sporck could accept none of these identities, national or political, but was saddled with one as a boy that became his albatross for life. He well knows what it’s like to live with the enemy—he is his own worst enemy.

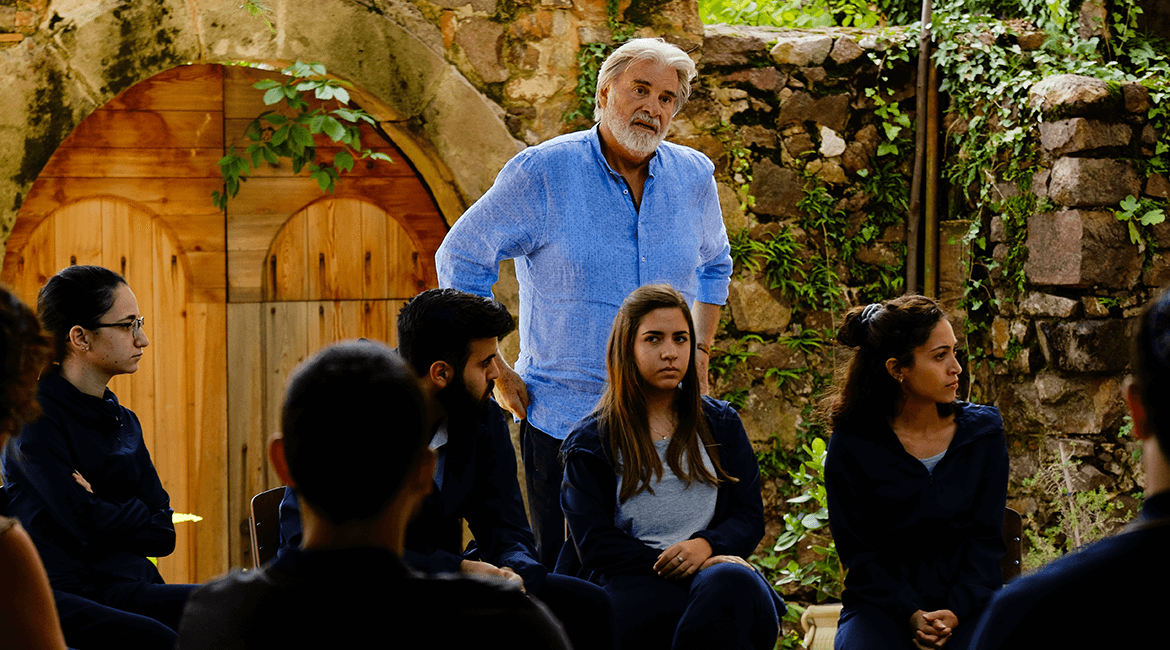

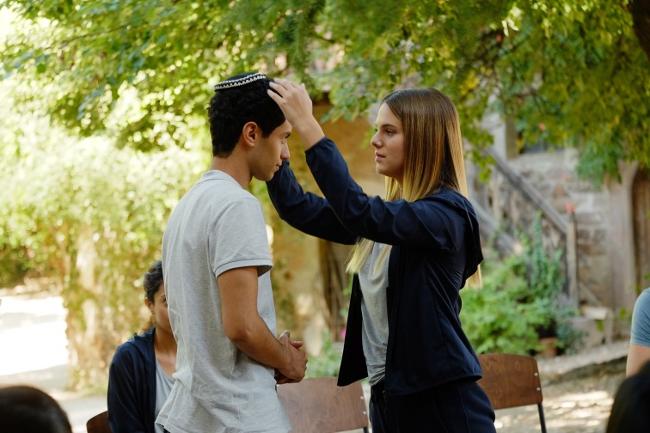

So with vast unwelcomed experience, he leads the musicians in numerous forms of group therapy: venting exercises, cross-the-line challenges, and walk-in-the-other’s-garb demos in which Omar volunteers to sport a kippah just as Shira dons a hijab. It’s no laughing matter as the Israelis snap photos on their smart phones to send home. The psychodrama enactments are the scariest, in which the maestro-turned therapist requires the youths to express every hostility they have ever harbored, eye-to-eye with the “enemy.”

Fear is always a lack of knowledge. It is lack of knowledge that brings instability, so it is important to know not only how to do something but why you are doing something. It is the same with music.

Daniel Barenboim

As they begin to face their demons, the musicians’ backstories slowly emerge. Layla’s family had to flee its homeland following Israel’s 1948 War of Independence. Sporck’s parents had to flee their homeland, Germany, at about the same time, following their practice as doctors perpetrating war crimes in Birkenau. He gets “down” with the young musicians by revealing a mysterious visit he has just made to a local Tyrolean woman who saved his life as a boy. His Nazi parents weren’t so lucky; they fled in vain, but “didn’t deserve to be saved,” he remarks. “It was my fate to survive as the son of mass murderers. It sticks on me like a blood stain. I never will be rid of this disgrace. It’s not only this tragic narrative but also the teller’s sober attitude that registers on youths who have been born into the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and have never seen any other way of life—or heard of it, until now. Just as Layla and Omar thought they would never see Europe, Sporck confides in them, “I thought I would never be able to travel to Israel, but then I accepted our project. I had to do so, go to Israel, and I did. I went to Tel Aviv, the lions’ den.”

If nothing else, Sporck would like the musicians to at least hear and feel themselves playing together, in concert with each other. That goal may be part of his own self-redemption. In fact, the film includes scenes in which, presumably at home in the region, he is attacked on the roadside, possibly foreshadowing a traumatic scene to come. Security forces, hired to protect the orchestra, urge him to ban the use of Twitter and Snapchat among the members. “That’s not going to go down well with these young people,” he replies. Meanwhile as they continue to rehearse, Maestro Sporck persists in showing them that it is not only their camaraderie that suffers but also their music. Why? Because they are not listening to each other.

Yet there is an exception to every rule, and Crescendo starts right off with its high point—a “mixed couple” that strikes up its manifesto loud and clear: #makemusicnotwar—the motto that is actually the second half of the film’s title. It also comprises the second half of the story, once this Palestinian clarinetist, Omar, and the Israeli French horn player, Shira, defy their rivaling “homies” and play out a Romeo and Juliet scenario—almost. Theirs is a gushing, blushing exchange of teen sensuality and audacity that actually looks far more natural than the kicking-and-screaming feuds the others persist in whenever their instruments are not in-hand. The interludes shared by Omar and Shira blossom like night-blooming jasmine, from the hillside chalet where they sneak visits in their rooms to a poolside reprieve from rehearsals that the ensemble enjoys, and the crescendo for this love-crazy couple is an underwater one, cleverly evoking for us, as music does, the unconscious fulfillment of our dreams and instinctive feelings.

It’s clear that history plays its own role in Crescendo, from the fraught audition and rehearsal atmosphere in Tel Aviv to the historic chalet-dormitory, offering a presumed sanctuary, in the hills of the wealthy South Tyrol (where, Eduard Sporck tells Karin de Fries, “farmers there did good business with the Nazis”). History is everywhere, and is being made everywhere. For his opening performance, Omar plays a soulful Arabic composition on his clarinet that he created himself; he is offered a place in the ensemble if he goes home to master a Mozart piece for the next day. Not only does he succeed, much to the surprise of the Israelis, but Sporck urges him to study music in at the university in Frankfurt. The film ends with a sobering and highly fitting musical homage to Omar that attests to the respect he has earned from his peers on both sides of what was once the “divide.” Such a piece, both musically and dramatically, reaches the true “crescendo,” as does Omar’s own composition, his clarinet notes filling the air from his father’s loud speakers as the man, weeping, drives through the streets of Qalqilya spreading Omar’s “story.”

A note about the cast who, it’s important to realize, are themselves from both Israel and Palestine, and just as the characters did, they also lived together for a number of weeks, in order to make the film. As thespians, they are exemplary. Daniel Donskoy is as gifted at acting as “Ron” is at the violin, and the dynamic Sabrina Amali as “Layla” adds fire and life to the film. The sweetness comes from two younger actors, equally promising, Mehdi Meskar as “Omar” and Eyan Pinkovich as “Shira,” both first-rate from beginning to end. And, of course, there is Peter Simonischek, an Austrian himself, so in-sync with the dialect of the region but speaking English for the young musicians, who once again delivers a soulful performance as he did in the German film, Toni Erdmann.

Perhaps there are two codas to a film such as Crescendo playing today. One has to do with relations between so-called “Western” nations and the Middle East; one has to do with the novel corona virus. Regardless of how little or how much this film itself resembles the efforts of Daniel Barenboim and the late Edward Saïd in forming the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, it’s interesting to consider the conductor’s comments to the UN News upon the ensemble’s performance at Carnegie Hall as recently as a year and a half ago, which included five Iranians and six Syrians—“miracle that they were allowed in the United States”—amidst a conflict that has raged internationally for at least 70 years:

We’ve had about one thousand musicians, give and take some, since 1999, and I don’t think one of them has not changed his mind about the other. Don’t forget that every Syrian who comes expects every Israeli to be a murderer, and vice versa. And here they are, playing together, tuning to the same A, playing the same phrase, with the same bow and the same breathing, the same, the same, the same, the same—this obviously has an influence.

Yet there remains another kind of gap to be bridged in a time when we cannot witness such marvels personally, physically, but only through a different kind of “mediation”—which, remember, is not only technological but social, and that is the Internet. Thanks to the efforts of a variety of cultural organizations, in this case the distributor Menemsha and the Southern California exhibitor Laemmle Theaters (among others), films such as Crescendo are accessible to a wider audience than ever.

Laemmle’s Theaters, for example, the Royal in West Los Angeles, the (Santa) Monica Film Center, and the Music Hall in Beverly Hills (now the Lumiere) have hosted Jews with family and ancestors from Israel, Germany, and Italy alongside of Jews, Muslims, and non-secular immigrants from Iran and the Middle East to sit shoulder-to-shoulder and view films from their own countries and from others, often with lively discussions to follow. At this moment, any resulting human bonding remains “virtual,” but hopefully, virtually true.

Crescendo can be seen at Laemmle’s Virtual Cinema: https://www.laemmle.com/film/crescendo-0

Crescendo

Director: Dror Zahavi; Producer: Alice Brauner; Screenplay: Johannes Rotter, Dror Zahavi; Cinematographer: Gero Steffen; Editor: Fritz Busse; Sound: Oliver Jergis; Music: Martin Stock; Production Design: Gabriele Wolff; Casting Director: Cassandra Han; Costumes: Riccarda Merten-Eicher, Julia Schell.

Cast: Peter Simonischek, Daniel Donskoy, Mehdi Meskar, Bibiana Beglau, Sabrina Amali, Hithram Omari, and Eyan Pinkovich.

Color, Scope, 106 min., English and German with English subtitles