9-27-09

Geliebte

Clara, I’m Looking for You: Helma Sanders-Brahms and Clara Schumann

By Diane Sippl

On Sunday, October 4th

the Goethe Institut Los Angeles will provide three ways to get acquainted with

the work of German writer/director/producer Helma Sanders-Brahms. At 11:00 a.m. the Institut will host an

exhibition of photographs documenting the making of two films, Clara by Sanders-Brahms and Klimt by Raoul Ruiz, both series of

photos taken by Konrad Rufus Müller. At

3:00 p.m., Helma Sanders-Brahms will make a guest appearance at the American

Cinematheque’s Aero Theater in Santa

Monica where her film, Clara will be shown as part of this year’s German Currents festival,

a sampler of the country’s latest works of cinema. The festival runs from September 30th

– October 5th, ending at the REDCAT in downtown Los Angeles.

I was lucky to view Clara when

it opened in

Not unlike the covetous drinkers

at a tavern in Germany who clipped the pearls from Clara Schumann’s satin gown

as she fled the concert hall post-performance to catch an earful (and an

eyeful) of young Johannes Brahms at that local pub’s piano, we flocked to

Mannheim’s gala last November for the world premiere of the latest by Helma

Sanders-Brahms, Geliebte Clara, (My Dear Clara, aka Clara). The reason: this

prolific filmmaker was one of the handful of women who had put

In Düsseldorf in the 1850s, after Clara and her husband (and not the other way around, since Clara was then the superstar of the two) have settled in from touring, he is to conduct the city orchestra while he composes. Clara, soon to become pregnant with their eighth child, helps him, and Robert increasingly relies upon her, but both of them also embrace the affectionate and increasingly necessary help of their friend and eventual soul mate, Johannes Brahms. In this highly theatrical film about musicians, what struck me most vividly was not the music but an image: a window to the Rhine in the stairwell of a sanatorium where Robert has been secluded over many months. Passing the “eye” to the Rhine, Clara informs Brahms that her husband has died. The image truly worked for me. That “eye” was a way of looking, a window out to the water, the ever-changing water itself a way of reflecting, a way of moving, that worked the way music does, but without trying to represent it.

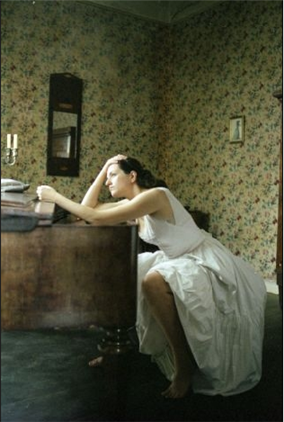

Unlike the films that gave Sanders-Brahms her name (in fact, she is a descendant of Johannes), Clara makes use of three celebrated stars. Pascal Gréggory as Robert Schumann delivers a face and body possessed with emotion — pain, turmoil, inner joy. A rambunctious Malik Zidi at 30 plays a 20-year-old Brahms a bit monkey-like at first, sliding down banisters and walking on his hands as if he were the young Mozart in Amadeus; he actually adds an abundance of charm, warmth, and persuasion to the film. Martina Gedeck as Clara — the namesake of the film and its presumed emotional and performative core — is a surprise. Subdued and rather passive in her behavior, or at least, mostly resigned given her personae, she is quite “the second sex” many women were in her time. Overtly challenged when she takes the wand for Robert at her suggestion, at a time when he no longer has the constitution to rehearse with his orchestra, Gedeck’s Clara can be disconcerting to watch. Brahms once observes her legs and feet from under the piano.

Sometimes Geliebte Clara looks like a cameo of Robert, not Clara, the

ever-beloved star of her era, who gave concerts for sixty-one years, but even then, focusing as it does on his last

years that are filled with outrageous suffering, the film leaves open to

interpretation the source of his ailment.

Is it alcohol or laudanum abuse?

A hereditary chemical imbalance?

Shattered nerves from the pressure and fatigue of touring, or even

composing? I did my own research and was

satisfied with the answers from books, but a hint might have drawn me closer to

Clara, for all her forbearance. As a mother (let alone as her husband's caretaker), regardless of housekeepers and

nannies, she must have experienced an overly taxing life. The children appear on the screen, but scenes

of her interactions with them are terse if tender. On the other hand, Brahms adores them: he

takes them swimming in the Rhine; he teaches

them arithmetic and English; he concocts a “picnic” for them on their floor

when the household furnishings have been sold off to cover debts during Clara’s

pregnancy and Robert’s treatment.

“I must practice four hours a day,” she states once. Often sound bytes such as this one replace dramatic dialogue with the bold relief of melodrama. These bold strokes supplant the nuance of an inner voice, even a quiet, complacent interior, that might disclose Clara’s point of view on her world as an artist in her own right, as a woman balancing career, motherhood, and marriage to a man who has grown physically and mentally ill. We witness one real confrontation: she refuses to give him her drugs. In a physical tussle, they slap each other in the cellar and she then conducts his musicians sheepishly pulling her hair over her swollen face and black eye.

The truth is that, according to

her own private words as written, she loved her husband until the day he died

and thereafter, honoring this feeling despite her attraction to Brahms and her

deep admiration of him. She would not

marry him: hence an early scene in the film and a later, climactic, one, make

ironic play of Robert Schumann’s wedding ring. In the final scene Clara wears rings glowingly on both hands as she performs Brahms' Piano Concerto No. 1 in D-minor, Maestroso (Op. 15). The camera gives us one of the film's most aptly used close-ups. What a pleasure it is to partake in the flow of expressions that come over Malik Zidi's face like shifting clouds in the sky.

In viewing Clara, I was reminded of an important consideration: music requires its own imaginary space. The same goes for words and images. When one creative form seeks to illustrate the other, the art is lost. Along with both Johannes Brahms and his descendant Helma Sanders-Brahms, Geliebte Clara, I’m looking for you…

Geliebte Clara (Clara)

Director: Helma Sanders-Brahms; Producers: Alfred Huermer and Helma Sanders-Brahms; Screenplay: Helma Sanders-Brahms; Cinematography: Jürgen Jürges BVK; Sound: János Csáki H.A.E.S.; Editing: Isabelle Devinck.; Production Design: Uwe Szielasko; Art Director: István Galambos; Costume Design: Riccarda Merten-Eicher; Costumes: Györgyi Szakács; Original Music: Robert Schumann, Clara Schumann, and Johannes Brahms performed by the Danubia Symphony Orchestra.

Cast: Martina Gedeck, Pascal Greggory, Malik Zidi, Clara Eichinger, Aline Annessy, Marine Annessy, Sacha Caparros.

Color, 35mm, 104 min. In German with English subtitles.