8-28-10

To and From La Scala: Carmen on the Screen

By Diane Sippl

Georges Bizet’s Carmen as performed at Teatro alla Scala, Milano, December 7, 2009

Thank God for mediated sounds and images, I am thinking at just this one moment, because these days, most any time, I would kill for a live performance of music or song, theatre or dance. But who would imagine that it would come to the point of audiences preferring to look at a giant screen image of the conductor waving his wand at the orchestra for opera music rather than at the singers themselves, their voices ringing from their demonstrative bodies and faces? When Gustavo Dudamel conducts Carmen at a 17,374-seat outdoor venue in Hollywood, it’s a whole new “Bowl” game. Opera for the masses? Conducting as “dance-theatre”? Video-mania? Or simply music incarnate?

The hallowed triptych of virgin/madonna/temptress, along with a soldier’s possessiveness, a matador’s machismo, and tarot cards thrown in for good measure, may seem as senseless to today’s educated audiences as fate and religion were to Marx and Freud in the heyday of opera (or as Marx and Freud are to students today), but at least in Carmen, the archetypes are not likely to die off any time soon, even if Bizet himself did, before he saw his opera thrive on the stage. On the contrary, as I write this article I am listening to Natascha Petrinsky speak in the intermission of a live radio broadcast of Gustavo Dudamel’s August 1st concert presentation of Carmen at the Hollywood Bowl and discovering that yes, in fact he is due to conduct the opera, within two months, in the very hall, Teatro alla Scala, where the film I am reviewing here was made from Daniel Barenboim’s rendition last December. Prior to this version, the one I viewed most recently was Carlos Saura’s 1983 dramatized dance version for the screen, so I cannot help but note that in 2004 Saura directed Erwin Schrott as Escamillo in his Valencia staging of Carmen as an opera, and that this very same Uruguayan bass-baritone will play the role in Dudamel’s upcoming production at La Scala, fresh from his concert performance of the bullfighter for Dudamel in Caracas a year ago. And who is slated to play the title role? None other than Anita Rachvelishvili, the Carmen of La Scala’s December, 2009 production, presented in movie houses in the U.S. through the “Opera in Cinema” series offered by Emerging Pictures, and the subject of this discussion.

Anita Rachvelishvili as Carmen

If it’s any consolation for the fact that the archetypal femme fatale is so alive and well in Carmen, the lyrics about smoking (of tobacco or any other intoxicant, such as l’amour) in Bizet’s libretto make for a far more seductive cautionary than any of today’s campaigns by the American Heart Association. The brigade of smugglers is right out of today’s headlines as well, and for that matter, so is a resonant image of their “earnings” — paper money they toss into the air in a burst of hedonistic exhilaration. More to the point, Carmen always was a pastiche: for Prosper Mérimée, in his novella published serially in France that read like a travel letter of exotic escapades in Spain; for Georges Bizet, who read those pages with a tantalizing barrage of dance music from Parisian cabarets buzzing in his ears; and for most others who would interpret the opera over the decades to come. (This is setting aside Francesco Rosi and his utterly organic 1984 screen adaptation of the opera per se, shot on-location in Andalucía, as stunningly persuasive as it is astutely interpreted.)

Flirting with very real issues of nationality and ethnicity, gender, social hierarchies and economic disenfranchisement, military occupation, and language, but sexualizing and romanticizing them within emerging codes of realism in late nineteenth-century literature, music, and theatre, Carmen is ironically anchored in no pretense of authentic representation, much as Bizet and others suffered for such charges. And it is exactly for this reason — vivid and colorful as the opera is in its contagious energy of music, lyrics, and libretto, and precise as it is in melodies, harmonies, and rhythms — that Carmen can be inscribed in endless ways. Carmen herself is one person’s black widow spider, another person’s free spirit; one’s selfish, guileless, depraved criminal, and another’s uniquely self-possessed, ingenious, delectably sensual survivor. Despised and deplored by many, admired and envied by others, and privately feared by all, her one indisputable trait is her magnetic attraction. In opera, this requires a voice, but it demands much more than that, a point well taken in considering La Scala’s recent production.

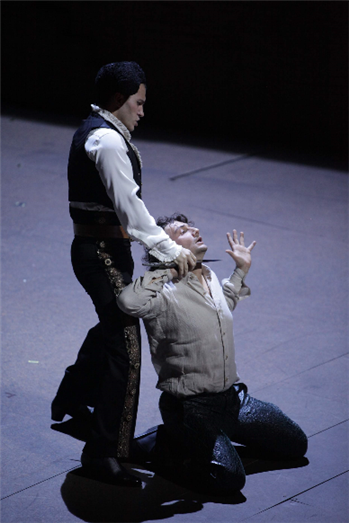

Jonas Kaufmann, center left, as Don José

Following that opening night performance, the director, Emma Dante, was greeted with mixed reactions at the curtain call, including enough boos to drown out the applause. The conductor, Daniel Barenboim, clasping her hand, brought her back out again, teary-eyed, through the closed curtain. The lead, Anita Rachvelishvili, received a rain of flowers; yet curiously, one bopped her in the face. Nonplused, she brushed her cheek, bent over to pick it up, and smiled — with a more radiant expression on her face than we tended to see during the performance. Of course, traditionally, the flower-bopping is her move: Carmen is supposed to throw a flower tauntingly at her love-object, Don José, upon their first encounter. In this performance, she does not; instead she whispers into the ear of a young girl next to her to do it, in essence keeping herself at one remove from any chemistry between herself and her man. That flower in her face at the curtain call was too ironic, and it was tempting to read it as an affront, or at least witty playfulness, or at the very least, unwitting fatefulness in response to an opera purportedly about fate.

Let’s start by saying that Carmen should have thrown that flower at Don José herself. That gesture, one of the most symbolic in the entire opera, is not only the basis for Don José’s “Flower Song,” (which turned out to be the most compelling performance of this production despite its detached set-up) but also the foundation from which Carmen sinks her hooks into her conquest. Hers is a carnal game; it plays upon physical sensations to elicit emotions. This chain of events never quite transpired in the Carmen I saw on the screen. Instead I saw another chain reaction: a Carmen that was very French, very dark, and very much Don José’s story. Bizet might have considered it just that, but I think that, like his rapturously pathetic soldier, he also fell for all the “Carmens” he knew and imagined.

Georges Bizet’s Carmen

as performed at Teatro alla Scala, Milano, December 7, 2009

The problem in Emma Dante’s version, as staged and directed, is that Carmen is so self-contained and Don José so sweetly tender, she so un-moving and he so moving, that it’s impossible to imagine a vile muscle in his body, let alone one aimed at her. And this matters as the story comes to an end. By then I could only pity José’s capacity for fantasy, and it left a bad taste in my mouth to realize that I was ready to condone and even empathize with a murderer for constructing some kind of goddess and punishing her for his fantasy. He is a jealous, possessive, powerful, and destructive force. It might appear that he has abandoned his fiancée, gone to prison, lost his military rank, joined a band of outlaws, become a murderer (in Dante’s version, a would-be rapist as well), and faces execution all in Carmen’s name; but also in this version, it’s hard to say that she’s the cause of his actions, or that she even seduces him to perform them. Could this be deliberate? In the end he looks like a misogynist lunatic — or simply an ill-conceived character. In either case, his final action is then baffling, and since it culminates the opera, the whole experience might seem for naught.

At this point it’s worth explaining that so much else happens upon the stage: for starters, the music, perhaps the strongest asset of the production. Daniel Barenboim’s orchestration is elegant, paced so as to offer nuance and depth to a performance more pensive than other lighter, brighter, faster Carmens. (So it’s disconcerting to see him successively springing from his perch like a slow-motion jack-in-the-box when his coat tails get stuck on the conductor’s seat, one of the “high-definition” treats a video camera can provide.)

Erwin Schrott , on the table, as Escamillo

Twenty-five-year-old Georgian mezzo soprano Anita Rachvelishvili, making her opera debut just out of La Scala’s own vocal academy, gives a confident and remarkably even performance. With more sonority than color, her voice is rich, deep, grounded, strong, and not capricious nor even lusty when it might be. Husky, yes. She is neither lithe nor vivacious, but planted in her stances, even in her spirit. More sumptuous than vibrant, she is sensuous in a latent, hidden, and so rather sinister way, given the lyrics of fancy and freedom she unleashes in song.

Jonas Kaufmann’s creamy vanilla lirico spinto tenor distinguishes his delivery. Such a voice alone might do the job, but Don José oozes from every move the German Kaufmann makes, from every look in his eyes, and he is therefore a perfect lure for the camera, which carries us straight to his heart. If Anita Rachvelishvili’s Carmen is without whim, fantasy, and play, Jonas Kaufmann’s Don José is almost loving enough to give her womanly wiles — just about. That being said, in this production Kaufmann is more discreet than visceral, more mannered than devouring. For a comparison, take a look at his 2006 performance in London as Don José, when at the end of his “Flower Song” he is so deranged and beside himself, he bursts into tears. If Don José is said to have no signature theme in the opera, Kaufmann makes one of his “Flower Song.” And even in the “Seguidilla,” the dance by which Carmen wins him over, it is he who seduces us, by one simple gesture, his hand on Carmen’s abdomen. It’s a humble, instinctive embrace he repeats elsewhere, and it lets us see him as the most — perhaps the only — sexual being in the show.

Erwin Schrott plays Escamillo as if machismo were just now born and went to heaven. His face is also made for the screen. While he struts his slick matador amply across the stage, never losing the posture that puffs him up mile-high, his cocked eyebrow and sugary smile let us see that it’s more vanity than pride pulling him along. He duels with Don José in the way he would with his bull, dancing his “Toreador” footwork as upon the table at Lillas Pastia’s tavern. Schrott’s singing can be both exciting and enticing, faltering only in the lowest range.

Jonas Kaufmann as Don José and Anita Rachvelishvili as Carmen

In 1894, shortly after he first rattled the theatre circuit with Mrs. Warren’s Profession, the drama of a high-class brothel magnate and her prudish businesswoman daughter that was then banned until 1902 in London and well after that in New York, George Bernard Shaw, a prolific music critic for The World as well as one of the best realist playwrights of the time, rationalized Carmen as follows:

“the success of Bizet’s opera is altogether due to the attraction, such as it is, of seeing a pretty and respectable middle-class young lady, expensively dressed, harmlessly pretending to be a wicked person, and… anything like a successful attempt to play the part realistically by a powerful actress must not only at once betray the thinness and unreality of prosper Mérimée’s romance, but must leave anything but a pleasant taste on the palate of the audience.”

In the same review of the performance by Emma Calvé, his personal matinée idol, he went on to describe Carmen herself as

“a superstitious, pleasure-loving good-for-nothing, caught by the outside of anything glittering, with no power but the power of seduction, which she exercises without sense or decency. There is no suggestion of any fine quality about her, not a spark of honesty, courage, or even of that sort of honor supposed to prevail among thieves. All this is conveyed by Calvé with a positively frightful artistic power of divesting her beauty and grace of the nobility — I had almost written the sanctity — which seems inseparable from them in other parts.”

Bedecked in shimmering, layered dresses of rose and plum, her golden face glowing without noticeable make-up, is Anita Rachvelishvili overly possessed of nobility and grace? Hardly. We get to see her plant a cigar between her lips and poke it in Don José’s face or throw him down onto the floor when need be. But in general she is withholding: a passive aggression simmers inside her just waiting to be plucked by the devil-may-care, free-wheeling flirt, Escamillo. Even he is more finesse than flair when it comes to the two people who matter, Carmen and Don José. He is insouciant with the woman, cagey with the man, and saves his panache for the table-top at Lilla Pastia’s.

Anita Rachvelishvili as Carmen

Is this coy, cat-and-mouse, “class” act, why is it that La Scala’s 2009 production strikes me as particularly “French”? The editor of Bizet’s Carmen, Burton D. Fisher, begins to capture my inkling:

“…Carmen became the great French connection in opera. French opera, like Italian opera, derives from the same Latin roots and origins. Both are mired in basic emotions and passions, and both usually deal with those same great primal conflicts of the spirit and the flesh, be it love, lust, greed, betrayal, jealousy, hate, or revenge.

Italian opera can be more direct, more declamatory, and much more naked in its passions, and most of the time, is intensely sizzling, as it goes right for the jugular and brings us right into the fray. But French opera, even though it presents those same Latin emotions and passions, generally can be more oblique, more subtle, even at times, overly refined and sophisticated, but not withstanding style and traditions, French opera, and particularly Carmen, delivers the same dramatic and emotional intensity as Italian opera.”

In A Short History of Opera Donald J. Grout summed up the reasons why Carmen is often considered “the perfect opera,” and he somewhat accounts for my sense of this production as “French”:

“Fundamental… is the firm, concise, and exact musical expression of every situation in terms of which only a French composer would be capable: the typical Gallic union of economy of material, perfect grasp of means, vivid orchestral color, and an electric vitality and rhythmic verve, together with an objective, cool, yet passionate sensualism.”

Bizet’s gifts as a Parisian composer are evident in Emma Dante’s Carmen. Dante shows her wish to highlight, upon a nearly black stage, the conceptual codes within which this lawless gypsy woman is threatening: faith and fate, Orientalism, music and dance as languages, all establishing femininity as mysterious and even inscrutable. These sites, when figured in the staging, point to the lofts of privilege from which José sinks into the alluring excess of Carmen’s song and charms. He surrenders his status to her on many fronts, yet as Susan McClary notes in Georges Bizet: Carmen, “it is ultimately Carmen who pays — with her life — for José’s identity crisis and Bizet’s fantasies of alterity.”

Erwin Schrott as Escamillo attacks Jonas Kaufmann as Don José

McClary reminds us how we dodge and brush out of mind the “lurid” context in which Carmen was composed:

“…we may no longer link the opera’s exotic elements with the colonized ‘Orient’ (in this case, Africa, the Middle East, and Moorish Spain), insubordination with the (Paris) Commune or female sexuality with syphilitic infection (through the engagement of prostitutes who have been infected). And we do not like to remember the enterprises — colonial wars, genocidal purges of European ethnic minorities, massacres of striking laborers, increased regulation of women’s bodies — that arose to counter nineteenth-century destabilization…. Whatever else it is, Carmen is emphatically not about fate.” (parentheses mine)

McClary, a musicologist, points out that in history, Austro-German audiences favored in Carmen what they noted as “French lucidity,” but that French critics at Carmen’s premiere in 1875 sensed an overwhelming influence of German music on Bizet’s composition.

By his training and mentoring, Bizet was steeped in Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Schumann, and he said of Wagner in 1867, “The charm of his music is unutterable, inexpressible. It is voluptuousness, tenderness, love!” At some cost to his reputation in a France suffering the Franco-Prussian War, Bizet was clear about his disposition. Biographer Winton Dean, in Bizet: His Life and Work, quotes the composer in a letter to Mme. Halévy in 1871:

“I am German by conviction, heart and soul, but I sometimes get lost in artistic houses of ill-fame. And I confess to you under my breath, I find infinite pleasure there. I love Italian music as one loves a courtesan…”

It has been said that Don José’s relation with Carmen is “endless melody.” In this sense the appeal of Kaufmann for me might be better suggested by Ernest Newman in More Opera Nights, who writes that Carmen is:

“the most Mozartian opera since Mozart, the one in which enchanting musical invention goes hand in hand, almost without a break, with dramatic veracity and psychological characterization… This is indeed music muscled in the Mozartian way, the fascinating way of the cat-tribe, the maximum of power being combined with the maximum of speed and grace and minimum of visible effort.”

A look at some key scenes reveals the choices for staging this production that define Emma Dante’s concept. Early in Act I, in the square in Seville between the tobacco factory where women work and the building that houses the dragoons of Almanza, a kind of national guard that “protects” the women all the while it surveys and polices them, a parade of relief soldiers is followed by a band of street boys who march behind, repeating the proud song of the military as if to mock its prowess. While the replacements, mere adolescents, are being trained, the urchins in the mock parade march as if crippled and saddled with burdens on their backs. Despite the high-pitched woodwinds and the brisk, merry tempo of the music with a boys’ chorus chirping, “Avec la garde montante,” the square is gray and bleak, and the humps on the urchins’ backs suddenly dismount as bare-chested tots, all in the same white underpants, like so many ghosts of war or poverty, conscripted youth brigades of today’s Middle East or Africa, haunting the stage with their cartwheels and tumbling disarray. The atmosphere and the attitude is already dark and dreary, the tone wry, in case we needed a hint that the visuals will work as symbolic (even sardonic) counterpoint in this production after we already saw Micaëla, Carmen’s antithesis, appear in a black coat covering her white lace dress that could only mean a virgin’s wedding.

Jonas Kaufmann and Anita Rachvelishvili

Chiaroscuro lighting, casting

shadows from above, carries along related motifs. The “cigarette girls” file out of the factory

in simple charcoal-colored coats over white or cream-colored knee-length slips,

all the same sleek contemporary cut, and wearing white cloths that double as

nun-like veils and bathing towels when they are flipped. It’s an austere, blatantly oppressive costume

choice for factory girls who are free-spirited enough to exit their work place

smoking and flirting as they head for the town fountain. It’s

the prelude to the “Habañera,” which Carmen sings in her straight and narrow

gray silk chemise for what is generally the opera’s most carefree, playful

song, teasing and taunting that it is. The

“Habañera” rests on Carmen’s possession of her own body and the flower of its

appeal; it speaks for freedom. Yet Anita

Rachvelishvili’s body language is as minimal as her dress and relies upon two

gestures, the incessant pulling up of the sides of her dress with her hands and

the occasional head jerks of her gorgeous lion’s mane of hair. Out of fondling solidarity, the other girls

lift Carmen’s body with much waving of bright flowers.

But what is surprising is that her seduction song for Don José, the “Seguidilla” to follow, is played in the same space with the same dreary lighting on an even emptier stage, save the draping of enough rope to figure a tug-of-war between Carmen and the man she would seduce. It’s dramatic, and in the end it becomes interesting to see her target, José, empowered to keep her captive, tethered just as she is — the result of a split second of snuggling between them — but this is still a very lean, mean, modern, and minimal way of performing the seduction that is the key to the opera’s conflict. Especially because the Habañera and the seguidilla are originally dance songs lifted from the streets of Paris because they dazzled Bizet, it hasn’t been unusual to see more beguiling performances of these songs and scenes in the opera’s history. Anyone who has ever seen Antonio Gades dance or choreograph Carmen (as in both Carlos Saura’s and Francesco Rosi’s films) might find the pelvic thrusts of the “Gypsy Dance” scene in this production equally curious.

Emma Dante, Director of of the opera Carmen, Teatro alla Scala, Milano, Decemebr 7, 2009

The rope dance, if we could call it that, sees a bit of a refrain in a “twirl-of-the-toreador’s-sash dance at Lilla Pastia’s tavern, where, fittingly, much is made of the ritualistic dressing of the matador. Here my best comparison is simply Sergei Eisenstein’s film, Que Viva Mexico, in which he ever-so-lyrically documents that country’s legacy from Spain by showing us all that it means to be a bullfighter. Catholicism is a key factor in the traditional ritual, and the Sicilian director of this Carmen, Emma Dante, peppers her stage with crosses big and little, black and white, intact and shattered, to this effect.

To better effect is the broad swing of an incense carrier smack toward the audience in a dynamic bit of stage business; equally unforgettable and theatrical are the unremitting appearances of what I can only call “masked maidens of death” (or are they “the five fates”?) virtually every time the death motif or the Toreador theme is reiterated by the orchestra. These white-robed, nun-like creatures in masquerade and sometimes pontiff-like headdress are a cross between popes and KKK riders except that they are ubiquitous on the stage, often perched like birds on a wire that might really be a balcony or high bridge but looks like the heavens on a dark set. These death maids are more conspicuous in the tavern in Escamillo’s “Toast” scene where they, too, lift their skirts, though counter-poised with Carmen. Their long, flared, stiff white skirts are so wide that when they lift the hems, their arms extended out to the sides, they can tip and tilt and twirl these skirts like ladies’ Spanish fans (think Manet), appearing even more flirtatious than Carmen, masks and all.

Then, reversing the motions of the coiling of the torero’s sash, these ladies unscroll not one but two giant photographs of slain bulls, blood and all, up against the edge of the long feast table covered with white lace, as if to torment human carnivores, or at least beef-eaters. This extreme verisimilitude, surrounded by highly symbolic sets and costumes, is glaring and shocking. We feel sorrier for the bulls than for the human victims of the patriarchy and Catholicism that the entire ritual serves to reinforce, yes, symbolically, but physically as well. And by the end of this Carmen, we are likely to ask, “Who is the bull being tortured and killed?”

This time, for all the ethnocentrism, sexism, and class antagonism the opera might take on, it’s too easy to answer, “Carmen.” The little crosses planted on the dark stage where the gypsies sleep on the ground in their camp symbolize a cemetery, but so does the bed in the background where a now black-and-white-stripe-haired Micaëla sleeps, suddenly doubling for José’s mother (and resembling Emma Dante!) as Micaëla is bringing news of her death to José in the mountains.

Daniel Barenboim, Conductor of Carmen, Teatro alla Scala, Milano, December 7, 2009

By now it’s clear enough that this production, rife with repetition, doubling (in sets, actors, and costumes), simulacra, embossed or brocade leather pants for men along with military-chic 21st-century jackets and caps, and baroquely dyed and printed organzas for women’s dresses and skirts, transpires in almost any time and place. Sets are mobile; costumes are convertible; hair is natural; make-up is negligible. In many ways this is not a fussy production. Most likely when it comes to Carmen — perhaps the most popular of operas across social classes, genders, and cultures — one person’s opéra-comique has always been another person’s kitsch, one’s avant-garde realism another’s cliché “easy sell.” Like the big screen on which I saw this production, Carmen itself has been a screen for the projections of everyone from Georges Bizet to Emma Dante.

As the filming of a live performance of an opera — “la prima” in Milano’s Teatro alla Scala, which emphatically opens the opera season every year on December 7th in honor of the city’s patron saint, Ambrose — this cinema rendition offers none of the pre-event hoopla that TV fans might expect, such as limos delivering cultural icons, business moguls, and international officials who all attend. Nor does it allow for the instant re-play feature that remotes make possible in home theaters where Europeans might be viewing the same event. Not even the intermission, behind-the-scenes interviews that radio emcees produce are on tap here. It’s opera. Pure and simple, minus a few instances of amplified booing from the upper balconies at the curtain call. But choice camera angles and distances can deliver a wondrous, seemingly un-mediated human experience: the voice of a young man singing of a flower presented to him. “From that moment I was yours!” José sings. Yet we might continue to ask, when that flower bonked “Carmen” on the face in front of the curtain, was she ours?

Carmen

Music: Georges Bizet; Libretto: Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy (after the novella by Prosper Mérimée).

Performed at Teatro alla Scala, Milano, Italy, December 7, 2009.

Conductor: Daniel Barenboim; Staging and Costumes: Emma Dante; Sets: Richard Peduzzi; Lights: Dominique Bruguière; Film Producer: Emerging Pictures, “Opera in Cinema” Series.

Cast: Jonas Kaufmann, Erwin Schrott, Anita Rachvelishvili, Adriana Damato, Francis Dudziak, Rodolphe Briand, Mathias Hausmann, Gabor Bretz, Adriana Kučerová, Michèle Losier.

Color, 172 min. In French with English subtitles.

All photographs courtesy of Emerging Pictures for the “Opera in Cinema” series.