3-30-21

Buladó: A Legend that Lives

By Diane Sippl

“Every feeling waits upon its gesture. Then when it does come, how unpredictable it turns out to be, after all…. Insight…comes in its own time, and…slowly and from nowhere but within. The sharpest recognition is surely that which is charged with sympathy as well as with shock—it is a form of human vision. And that is of course a gift. We struggle through any pain or darkness in nothing but the hope that we may receive it, and through any term of work in the prayer to keep it.

…my wish, indeed my continuing passion, would be…to part a curtain, that invisible shadow that falls between people, the veil of indifference to each other’s presence, each other’s wonder, each other’s human plight.”

— Eudora Welty, One Time, One Place

“As a filmmaker, I am aiming to show the elusive, something that allows people’s differences to disappear; be it love, mysticism, or an existential dilemma. By bringing this story to the big screen, I hope to open eyes to the beauty and power of the underexposed stories of our Dutch colonial history.”

— Eché Janga, Writer-Director, Buladó

She’s always with me. The wind. She caresses my face when I’m lonely. And blows tears from my eyes. She makes tangible what I can’t understand. Like death.

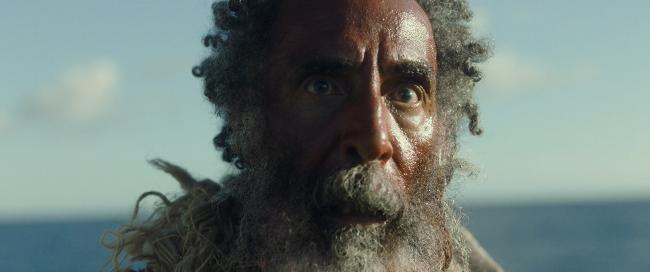

In a pre-credit sequence that begins with gray clouds swelling across the frame, the off-screen voice of a girl whispers her own sensations. Golden dust whips up shadows from the land—then a close-up of a horse and the torso of its dark, bare-chested rider, a man in a feather headdress and necklace, galloping along the green hills on the horizon as the crow flies, thunder rumbling under the low chimes of an organ—a dirge, and the title: Buladó.

Can it be possible to express the history of colonization for over half a millennium through the eyes and heart of a single girl? Could one effectively use the art of cinema to let us experience this tragedy, as the writer Eudora Welty speaks of her photographs, “so widely and yet close at hand?” Eché Janga’s film is the story of one child, on one tiny island, at one moment in her life—her emergence as a woman. Two men strive to show her the way, her father, and his father. And not far out of the picture are those who have died before her.

By many standards, Kenza is different, but “different” is itself a relative word—different from…? Whites? Blacks? Continental girls? Island girls? More to the point, Kenza is her own person. We first meet her close-up, the camera angle on her amber face depicting her cheeks as a cross between mumps and baby fat. She’s eleven, and her deep-set eyes peer off into the distance in our wide frame. What could she be surveying, contemplating? Her first action is to pull out her slingshot on an iguana, slay it, and pitch it for sale to a pack of post-pubescent males riding their dirt buggies in crazy circles on the desert sands of Curaçao. But before she can get her price, a cop car turns up and she’s “busted,” until after the officer throws her bicycle into the back of his station wagon, and she takes the front seat beside him, and he tells her to “buckle up,” at which point he himself takes her for a whirlwind ride, spinning circles, kicking up the dust, as she begs him to stop through screeching giggles.

It’s as if Ouiro, this man who is her father, is competing with the boys for her respect and attraction. Likewise, she herself competes for his attention while he admonishes a pretty worker for blocking the road with her catering truck. Indignant about this show of disrespect for her mother, Kenza blasts the car horn and gets him back behind the wheel. Moments later at home in the bathroom Kenza discovers that she herself has become a woman now even though, childishly uncomfortable, she hides her blood-stained underpants inside a big sock and tosses it into the wash basket. At the check stand in the supermarket when the cashier asks her who will use the sanitary napkins she’s buying, she replies, “My mother.” The lady isn’t satisfied and tells the girl she’s rude.

At school Kenza eats her lunch alone, and when a wimpy boy on the playground calls her a tramp with a cop dad and a crazy grandpa, she charges into him and pushes him over. “Who else wants a piece?” she cries out to the gathering crowd before she’s dragged off to the Principal’s office. In general, Kenza has no qualms about showing up without her uniform or simply ditching school altogether.

“Could this be because she’s missing a mother figure?” asks the Head Mistress.

“That’s not the issue,” insists Kenza’s father. “They never had the chance to look into each other’s eyes. You can’t miss what you never had.” It’s a remark Kenza overhears as she waits outside in the school hallway, but it’s one she’ll never forget. How can she not miss her mother?

Flying Fish Don’t Drown

Kenza may be the only girl on the island who knows how to repair cars (and does so, in her own front yard), and she might behave like a thoughtless boy when she pulls off her school T-shirt to wipe the debris from her mother’s tomb, but the gesture launches a series of actions for mourning her mother as a girl: insisting that her father style her hair by using her mother’s comb (now a precious heirloom), secretly donning her mother’s red earring, and finally stealing into her deceased mother’s closet for the woman’s white lace gown—not to wear it but to blot the bloody wound of a dead dog that had become Kenza’s only real friend. She hauls the dog on a blanket from the road into her house, lies down beside it, drapes the dress over the dog, and embraces it—one of the most heartbreaking scenes in the film.

The earlier scene at the cemetery, the first time we see Kenza lying down prone, links other deaths to her mother’s. A medium shot of her body stretched over the tomb as her mother’s body would have been laid to rest, and gazing up at the clouds, pulls back from the girl to a wide shot revealing hundreds of adjacent tombs covering the land, the moaning of the oil refinery on the horizon. When she returns “home” we see how three separate dwellings really make up the space—the house that belongs to the patriarch, Ouiro; the old, defunct family car amidst the vast wrecking yard that is her turf, Kenza’s hide-out where she communes with her mother via a cameo photo hung from the rear-view mirror; and the tent that her grandfather, Weljo, has built for himself, from which he can easily shoot any “trespasser” who wants to buy the property his son would sell to a foreign developer. Weljo doesn’t tolerate strangers on his territory. “Tears of slaves, their sweat and blood, inhabit this soil,” he scowls at his son. Weljo is building a tree to the spirits, and “when the wind turns, something magical will happen.”

Yet what that magic portends is the second family death, and Kenza is more acutely aware of it than her father. Weljo takes her to the museum to encounter the world of their ancestors, and he insists on breaking the padlock at the back door instead of entering through the front. “As if I’m going to pay for my own culture…” he quips. He refers to the ritual clothing of the Caquetios mounted on the wall, the garb they wore for their “long journey” …the one when the tree starts singing and the horse whinnies and the bird of prey leads the way through the air. Weljo begs Kenza to help him die in this way, for only then can his spirit return young and strong. Not only that, but he enlists her in his ancient rituals, taking her into the seaside caves inscribed by indigenous Curaçaons and teaching her the chants. But Ouira, a rational man, sees his father’s Spirit Tree as just another piece of wreckage that needs to be cleared for him to sell the land, so he tears it down.

That’s a turning point for young Kenza, who has come to feel more empathy from her grandfather than her father as she senses the loss of her mother. And yet, it’s hard not to see the pain that Kenza’s gestures of mourning bring to Ouira, for he, too, suffers the loss of his beloved wife, and unconsciously, the loss of his father soon to come. Yet all he can do is mock them in their mysticism. (“We are all the breakers of our own hearts,” Eudora Welty tells us.) Can Ouiro learn to understand the values of his father and daughter? More than once, the camera frames doubles of Ouira and also Kenza, who has now “turned” to Weljo’s spirituality, just as the wind will soon “turn” for him. That night, out of compassion, wearing goggles and work gloves, Kenza builds a metal scaffold platform, hauls long pipes, hoists them up on a chain pulley along with old hubcaps, carburetors, and oil cans, and welds them all together. She erects her own Spirit Tree for her grandfather, and will call out their ritual chant, repeatedly, rhythmically, “Piská buladó. Piská buladó…” (“Flying fish don’t drown. Flying fish don’t drown…”)

The film’s foregrounding of the oral tradition as the legacy of Curaçao, the omnipresent wind that Weljo endows with supernatural powers in the land-sea-skyscape of Bandabou (a barely developed region of the island), the alternating saturation of red, gold, orange, green, and blue lighting of chiaroscuro faces against the black of night, the haunting song-without-words of the bowed vibraphone on the soundtrack, and the dynamic play between close-ups and wide shots—a place in the heart and a place in the world—that become the same in the sprawling space of the cinemascope frame, might suggest the familiar genre of magical realism so prevalent in the Caribbean and neighboring Colombia; however, in particular the white lace dress dancing on the clothesline signals a mythopoetic language that takes on another dimension accentuated by silences enlisting reflection.

Once Kenza has “made contact” (as Weljo puts it) with her deceased mother, her watch stops. The past, present, and future (Curaçao’s conquest and slavery, its status as a crown colony, and its development in the global economy) merge. And as time stands still as if to take stock of the moment, the bodies double, Kenza’s, Ouiro’s, and Weljo’s each taking on two forms even if in subtle and realistic ways. The doubling is, then, not only representation, but a force of presentation. This blurring of entities is symbolic of the occasion for self-creation, for each to engender another self. Out of the lamentation of loss (relating to race, tradition, power), a surplus of language emerges so that the reality we experience is not simply what can be figured on the screen but also what covers it, surrounds it, and exceeds it—a breeding ground for self-renewal. Curiously, though he discusses this process in music and literature (and also includes religion, dance, and theatre), Achilles Mbembe portrays it in cinematic terms:

“…the question is no longer knowing the essence of loss—it is knowing how to create new forms of the real, floating and mobile forms. It is no longer a matter of returning to some primal scene at all costs, or of re-creating the gestures of the past in the present. Though the past has disappeared, it is nevertheless not off-screen (hors champ). It is still there, in the form of a mental image. One crosses out, erases, replaces, effaces, and re-creates both forms and contents. One proceeds by jump-cuts (faux raccords), discordances, substitutions, and assemblages—the condition for achieving a new aesthetic force.”

Yet, of what use is this aesthetics in the history of colonization and the world to come? Again in the same source, Out of the Dark Night, as he discusses his term, “Afropolitanism,” Mbembe speaks with a filmic imagination:

“The goal of artistic creation is no longer to describe a situation in which one has become a walking spectator of one’s own life because one has been reduced to impotence as a consequence of historical accidents. To the contrary, it is a matter of bearing witness to the broken man who slowly gets up again and frees himself of his origins…. In the age of dispersion and circulation, creation is more concerned with the relation to an interval than to oneself or another… (one) open to many forms of combination and composition.”

Janga builds his film through an imbrication of images that continually overlap as layers of meaning. Near the end of Buladó is a scene in which Kenza once more “lies down” at a key moment. This time it’s not with her mother (above her grave) or her dog (beside the corpse) but next to her father, just as, inevitably, “the wind turns.” She senses it, knows it, and moves—takes off—to enact all that the film is about. The sequence of events is key: the interval has come—for the movement of life in death, the future in the past, the world as a home. Movement, no longer frozen in time and place—an allegory of cinema and an allegory of Curaçao, from colony to territory to country.

Buladó: An Old Flight, a New Path

On the island, there is a mountain around which a legend has emerged. The slaves who had fled the salt mines and had not eaten the salt of the mines could fly from there back to Africa, to their freedom. Close to this mountain are caves where part of the indigenous population lived that helped to free the enslaved from their chains. They could jump off the mountain at night and the wind would take them back to the land from which they had been stolen.

— Eché Janga, Writer-Director, Buladó

Buladó is very much about death, loss, mourning, and yet, in this one place in the world, these few moments in time, these days in the life of an eleven-year-old girl lost in a liminal whirlwind, the soulful beauty of her convictions looks like the eye of the hurricane, not the storm. To be sure, Kenza is a force to be reckoned with. She can defiantly whip up anyone’s good day into an emotional disaster, but she is, for all her tempestuousness, rather the calm in the deep blue sea, the ray of light in the sky, and the more we follow her relentless rebellions, the more we understand the scope of her world. She (not the wind) makes tangible what we might never think to imagine.

It’s tempting to construe the word “buladó” as translated to mean “the wind” on the tiny, arid island of Curaçao, seemingly floating in the azure sea and sky of Antillean history and geography. Does the land belong to the South American coast, the Caribbean archipelago, or the Kingdom of the Netherlands? As part of the Leeward Antilles, Curaçao shares a political and economic legacy with each of these dominions, near and far, as well as with Spain, and England, and West African countries. Early on, in the days of the Spanish conquest of the Americas, Curaçao’s indigenous Arawaks and Caquetios were enslaved with the hope of harvesting the agricultural bounty as found on other islands of the region. Horses, cows, goats, pigs, and sheep were brought, but the land itself proved as useless for crops as for precious metals. The salt mines were an exploitable resource, and slave labor was deployed there, but once the Dutch freed themselves from the Spanish in 1634, these Northern Europeans expanded their shipping enterprise to the island to engage in the lucrative business of international trade, mostly of humans, establishing in Curaçao the auction blocks on which African slaves were bought and sold, and then providing the ships to transport them to other Caribbean islands and beyond. With slavery abolished in 1863, the Netherlands had to wait until the 20th century for a breakthrough in economic sustainability for its faraway outpost, and it came with the discovery of oil.

At that time Curaçao’s closest neighbor, Venezuela, needed a large-scale refinery for its leading export, crude oil, and by 1918 Royal Dutch Shell built Isla, the largest oil refinery in the world, on this small island, taking advantage of its natural deep-water harbors for shipping it as well. Operated by Petróleos of Venezuela on a long-term lease from 1985 to 2019, despite an unsafe level of carbon emissions, Isla managed to produce 90% of Curaçao’s exports—refined oil; but the island became its own “country” in 2010 (while remaining within the Kingdom of the Netherlands), and beginning in 2017, negotiations by its state-owned RdK to restart Isla have passed from China to Germany to Egypt (through the Dutch contractor from the former Shell). Tourism has long served Curaçao’s economy, but a year of the COVID-19 pandemic crushed it. Elections in March, 2021 have brought a new administration seeking a new economic relation to the Netherlands. At the same time, the young country is striving to diversify its economy through its Open Arms policy, pursuing foreign investment, especially with information technology companies, that can enhance its already strong presence as a financial services center (its Central Bank, established in 1828, is the oldest in the Western Hemisphere).

Yet back to buladó, which means not “the wind” (in fact a rather passive metaphor if it implies casting one’s fate to it, or being blown wherever it carries one); on the contrary, buladó means “taking off”—a willful, deliberate leap (of faith, commitment, or sheer imagination). In fact, Kenza herself is a product of Curaçaon buladó by the mere fact of her birth. Her mother died in 2010, the year the old regime of the island died, and the “offspring” Kenza, now 11 years old, is the progeny who will pilot the new country. Kenza is a grand negotiator— between life and death, between spirituality and reason, and between cultures. Her father wants her to become fluent in Dutch so that she can study in the Netherlands and prosper amidst multiple opportunities. But at one point she calls him as a makamba (a curse word for “white man”) and tells him to just go to Holland where he belongs. She speaks the island’s native tongue and official language, Papiamento, itself a Creole mixture of Caquetios, African, Portuguese, and Spanish, while a smattering of English and Dutch come up intermittently in the dialogue.

Yet the métissage of speech, organic as it is in the syncretism that makes up the history of Curaçao, is only one form of mixture the film plays up. The two men, Weljo as the diviner of native spirits and Ouiro as the enforcer of imperial law, embody more than ancient and Old-World regimes; they tug at Kenza and leave her no choice but to create her own New World order, one that demands interrelationships, fluidity, and change.

Bricolage is Kenza’s language, less spoken than enacted, such as her re-purposing of parts and labor as a car mechanic to show honor and respect for Weljo’s vision. Unspoken gesture is more often her tool as she either slugs her dad in the gut or literally reaches out to him, which she does several times, be it with her mother’s comb or a fossil of calcified coral, an endangered species of Curaçao, that she begs him to place on her mother’s grave; with her outstretched arm, she entreats him each time to redeem and renew himself by acknowledging loss—not only of his wife and his father but also his ancestors, natives and slaves alike—and sharing it.

Ouiro is one anchor of the bridge Kenza builds of innovative relations between old and new in structuring the solidarity and conviviality necessary for humanity. Out of the very créolité into which she was born, Kenza, through her own personal technology of the self, embraces her elders near and far as a newly formed woman, an independent being however much she is their progeny, and shows them an alternative way. In Janga’s mythopoetic tale of coming of age, Kenza learns to build her own “ship” of seemingly contradictory shards of culture and navigate waters that were always her “own”—but seas that, by their very evolution, require new navigation. “My mother is white and Dutch, and my father is Black Curaçaon. For me, it’s always normal to have these two cultures in one house. But my house is a small piece of Curaçao,” Eché Janga tells us. Yet his film is a big piece of the world today.

Buladó

Director: Eché Janga; Screenplay: Eché Janga, Esther Duysker; Producers: Keplerfilm, Derk-Jan Warrink, Koji Nelissen; Cinematographer: Gregg Telussa; Editor: Pelle Asselbergs; Music: Christiaan Verbeek; Production Design: Robert van der Hoop; Sound Design: Mark Glynne, Tom Bijnen; Costume Design: Josine Immoos

Cast: Tiara Richards, Everon Jackson Hooi, Felix de Rooy

Color, Widescreen, 86 minutes, in Papiamento and Dutch with English subtitles.