9-27-09

Thomas Mann Yesterday and Today: Buddenbrooks:

The Decline of a Family

By Diane Sippl

“A real book is not one that’s read, but one that reads us.”

W. H. Auden

It’s a witty expression of a keen observation by the poet who, for all practical purposes, married the daughter of the author Thomas Mann. Of course this was after both Erika Mann and her father were to see their citizenship revoked in Nazi Germany and Mann fled to the United States, first to Princeton University to teach, but ultimately to Pacific Palisades, California, in 1941, to set up a family dwelling and write, just a couple of miles down the street from where the American Cinematheque’s Aero Theater now stands in Santa Monica, where from September 30th through October 4th (and at the REDCAT on October 5th) the Goethe Institut Los Angeles is showing the “German Currents” series of recent films. Writer-director Heinrich Breloer, producer Matthias Esche, and actor Armin Mueller-Stahl will be on hand for the screening of their 2008 film, Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family from the renowned novel by Thomas Mann.

The Pacific shores gave the sixty-six-year-old Thomas Mann safe haven to complete two novels and write a new one, Doctor Faustus. Until 1952, he would find productive peace in the Palisades, where he could say,

“I have what I wanted — the light; the dry, always refreshing warmth; the spaciousness compared to Princeton; the holm oak, eucalyptus, cedar, and palm vegetation; the walks by the ocean which we can reach by car in a few minutes.”

Yet he sometimes also experienced

an intemperate sensuality in the locale, writing to a friend, “Here everything

blooms in violet and grape colors that look rather made of paper. The oleander… blooms very beautifully. Only I have a suspicion that it may do so all

year round.” For this experienced

traveler, the

“Exile creates a special form of life, and the various reasons for banishment or flight make little difference, whether the cause is leftism or the opposite — the sharing of a common fate and class solidarity are more fundamental than nuances of opinion, and people find their way to one another.”

In a chapter of Joseph and His Brothers that he wrote in

A few years before he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929, he addressed the city of Lübeck, Germany, to let the citizens of his home town know exactly how his epic novel, bundled up and sent off to a publisher just after his 25th birthday — the 800-page Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family — was really a reading of them.

In a public lecture in 1926 that he called, “Lübeck as a Way of Life and Thought,” on the occasion of the 700th anniversary of the city’s founding, Thomas Mann spoke to the townspeople of the new psychological prose of the naturalistic novel that combined vital statistics of daily life (births, baptisms, weddings, deaths) with both “pessimistic metaphysics and satirical characterizations… seemingly the very opposite of love, sympathy, attachment (and more about) the bird that befouls its own nest.” He related how, beginning to write Buddenbrooks in his early twenties, he had injected into it his “un-Lübeckian” intellectual experiences, such as Schopenhauer’s dark philosophy and Nietzsche’s psychology of decadence. But after finding models in Scandinavian family novelists, who set their stories in trading cities, and in Turgenev, Goncharov, and Tolstoy as well as Wagner’s Ring cycle with its intricate fabric of leitmotifs, Mann then needed to research Lübeck’s own business history, municipal activities, economics and politics, so he sought out his father’s cousin who advised him “in a soldierly way.” Upon completion of the two volumes, the budding author then found a publisher who conceded that there were indeed books that amounted to nothing if they weren’t copious. But the critics jumped on him:

“What’s this? …Are bulky tomes to come into fashion again? Is this not the age of nervousness, impatience, brevity, a time for slashing and artistic sketches? Four generations of a bourgeois — what a bore!”

The critics compared the novel to a heavy dray grinding its way through sand. Yet in tracing the history of his own family in Lübeck, Mann had also rendered a fragment of cultural history, in particular, a psychological portrait of the German burghers that revealed the European patrician sector in general: the process of “the loss of bourgeois values, bourgeois competence, through differentiation, through the excessive development of sensibility.” It wasn’t just the hyper-sensitive musical prodigy Hanno and his uncle Christian, passionately drawn to the theatre, who were to drive the narrative with their oppositional force, but even Hanno’s father, Thomas Buddenbrook, proprietor of the Protestant business ethics of the North, and his sister Tony, who would aspire to these ruthlessly competitive values complacently. Thomas Mann was fascinated by the unconscious and the extent to which every significant action sprang from the “will” that was inadequately or belatedly informed by the intellect.

“How often in my life have I not

observed with a smile that the personality of my deceased father was governing

my acts and omissions, was serving as the secret model for them?” Mann wryly

asked himself. And there was his mother, with her “blithe southern

disposition,” of Portuguese Creole descent from her father’s days of doing

business in

Mann felt that Lübeck as a city, as an urban scene with its own urban character, “as a landscape, language, and architectural complex,” not only played a role in Buddenbrooks but also stamped his entire literary output. Yet what was that “landscape”? The author acknowledged critiques of his work that claimed his descriptions of landscape, or the lack thereof, were his weak point, but he countered them. First, such critics were ignoring the significance of the sea, in this case the Baltic Sea, which Mann first experienced as a boy in Travemünde:

“That was the Travemünde of forty years ago, with the old Kurhaus in Biedermeier style, the Swiss chalets and the concert hall in which little Kapellmeister Hess, with flowing hair and gypsy-like demeanor, conducted his crew. I would crouch on the steps in the summery fragrance of the beech tree insatiably drawing into my soul music, my first orchestral music. It did not matter what was being played. There in Travemünde, the holiday paradise, I spent what were undoubtedly the happiest days of my life, days of profound contentment, of wishing for nothing at all…. There music and the sea merged into one within my head and heart. And from this emotional and ideational conjunction something new was born: namely, narrative epic prose. Ever since, for me the idea of epic has been linked with the sea and with music.”

Regarding the images he painted, he claimed to make use of the palette of the sea: “If my colors have been found subdued, not luminous, the reason may be certain glimpses through silvery beech-wood trunks of a pastel sea and pallid sky, upon which my eye rested when I was a child and happy.” Referring to Lübeck’s “natural frame” in addition to the Baltic Sea, Mann insisted that none of the “excessive azures of the gracious South” could diminish the “pure, fresh, and idyllic impact” of his impressions of the district of Eutin, Mölln, and Ukleisee that were in his books, but not as overt word-paintings.

Thomas Mann encouraged his readers to consider various “modes of being”: for example, the atmospheric as opposed to the physical, or the acoustic instead of the visual. People, especially artists, he maintained, have been classified as either aural or visual, some experiencing the world chiefly through their eyes and others, mainly through their ears. He even went so far as to attach the latter sensibility to the North. He perceived its landscape acoustically.

For Mann, if the landscape of a city was not only its architecture (such as Lübeck Gothic) and the rhythms and musical transcendence of the nearby sea, it was also the spoken language — “its mood, tonal quality, intonation, dialect; as the very sound of home, the music of home.”

Mann described his writing

process as one in which the book “swelled under (his) hands… hibernated during

the winter, awoke again, proved to be as absorbent as a sponge, grew by

accretion like a crystal, (and) drew all the elements of the times to itself” —

an organic growth and refinement to allow the scale of the project its own cadences

and time frame.

“My style has been characterized as cool, unemotional, restrained. It has been said — in praise or blame — that it lacks grand gestures, passion; that it is the instrument of a rather slow-moving, sardonic, and conscientious mind rather than that of a tempestuous genius. Well, I have always been cognizant that the literary landscape which can be described in such terms is Low German, Hanseatic, Lübeckian.”

In 1926 at age 51 Thomas Mann closed this talk by referring to himself as a “bourgeois storyteller who all his life has actually told only one single story: the story of the burgher who sloughs off the burgher’s skin. Not in order to become a capitalist or a Marxist, but to become an artist; to achieve the irony and freedom of art, and art’s capacity to flee and to fly.”

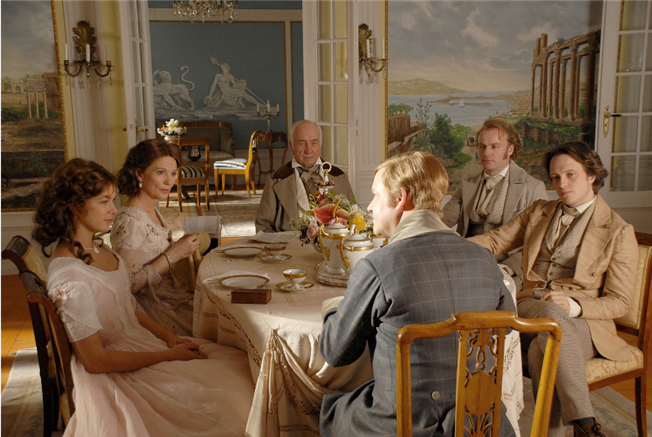

Flee he did, within seven years’ time, landing in Pacific Palisades sooner than later and flying through the autobiographical fictions that continued to fill his pages. Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family had already been adapted to the silent screen and was to see four other incarnations for film and television. They tend to be longer than the latest, by Heinrich Breloer, even up to ten hours, pointing to one of the challenges in preparing visual media from a novel of this scope. But as is suggested in the above introduction, other questions arise: how to convey Mann’s meticulous detail, his sense of impending fate over prolonged time, the non-theatricality of the family’s cool, middle-ground ethics, a temperate palette and lighting register that still save the novel from becoming a sentimental romance. Locations, sets, and costumes are another matter, commanding a budget.

Selection and omission, condensation and expansion are always at issue in adapting literature to the screen. Thematic focus and tone are concerns; yet they can vary from one medium to the next without sacrificing artistic merit for fidelity to the source and vice versa. Heinrich Breloer lavishes 152 minutes on Mann’s four generations of his mercantile family between 1835 and 1877, years that saw the 1848 Revolutions and the North German Confederation on the way to the establishment of the German Empire.

Mann allows these events to intervene, giving them their space although in perspective, foregrounding the daily pressures of the Buddenbrooks’ buying and shipping and selling, the precise and concrete details of the family’s Protestant and patrician rituals and civic duties, and their financial threats and responses, all of which make up their “ethics” and therefore their cumulative “destiny.” Thomas Mann uses a symbolic aesthetic to express the interior and exterior tensions between the worlds of art and commerce, a dynamic that appears to compel screenwriter/director Breloer, but differently.

Having previously worked in television (presenting the Mann family, no less), Heinrich Breloer here brings a steadicam world to Lübeck’s way of life, through our own century’s lens. His camera roves and zooms as if Scorsese’s in The Age of Innocence, and Armin Mueller-Stahl whispers as softly as Brando in The Godfather, even if more eloquently. The film opens with the Hagerströms and the Buddenbrooks taunting each other, as children racing each other in wagons and doing damage, kissing each other and slapping for it. Half a minute later, they are adults. To boot, we’ve skipped the whole first generation.

The old families and the new ones,

the established and the upstarts, look voyeuristically at each other through

windows and curtains, eavesdropping and exchanging looks, and the frame is used

to enclose choice cinematic spectacles: from the street theatre of the tiny

tots to the grown Buddenbrooks lined up and primping in the mirror at the ball,

or waltzing and talking of dowry sums and their dark counterpart, illicit sex. The pace and thrill of the fast and furious

camera are matched with rapid editing and theme music that swells between the

scenes. “Buddenbrooks — polished on the

outside, black on the inside,” shouts Christian on the street to Tom when he

detects the smell of roses and warm, damp soil on his older brother. “Countenance — Discipline — Balance — the

Company Requirement,” they chant as they brace themselves to return home

following their private “after-parties.”

Tony, their sister, about to be financially negotiated into a marriage, is robust and defiant, nearly altogether devoid of restraint and possessed of 21st-century manners and mannerisms that would be highly uncouth and unacceptable in her day and social order. She is a storm of refusal (like the rainstorm that follows her home in departing from her new-found lover): “Nein, nein, nein!” she cries regarding a forced engagement to Herr Grünlich, her heart consumed with the harbor pilot’s son she met a minute ago, who stripped to the waist before her on the beach to go charging into the waves for a swim and shouted from the water his secret — he’s a “Dangerous Democrat!” It’s about all we hear of his politics, but the chemistry is there, which seems to be what counts in the film, setting all improprieties aside (he proposes to her through her bedroom window, Tony in a delicate white nightgown).

“You were born a Buddenbrook,” her father tells her before he soon dies. “We are not born to pursue our own small personal happiness, with our own short-sighted eyes. We are links in a chain. It is inconceivable that we would be what we are without those who have preceded us.” And in Mann’s book, those very people, over generations, have persuaded Tony, with all proper decorum, to choose willfully to enter the prescribed marriage contract between the families and fortunes. She herself subscribes to an “exile within walls.”

In the film, within moments of Jean Buddenbrooks teaching Tom, “We only know the worth of a shipment when the goods have been sold for a profit,” Grünlich is garnering an extra ten thousand marks above the seventy thousand set aside for a Buddenbrook dowry and the wedding is on. Tom is sent off to Amsterdam to extend the firm’s interests and his own, and Christian is headed to London to do the same. It is precisely the matters of the heart (and the flesh) and the sibling rivalries that will prevail to tell the balance of the story.

To his credit, Breloer has chosen a superb cast and they take full command of their roles. The three siblings of the one generation — Jessica Schwartz as Tony, Mark Waschke a Tom, and August Diehl as Christian — carry the film with panache. Their work is well complemented by that of Léa Bosco as Gerda Arnoldsen and Raban Bieling as Hanno, who are married into and born into the family, respectively, and join its demise.

Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family

Director: Heinrich Breloer and Horst Koenigstein; Producers: Matthias Esche, Michael Hilde, Jan S. Kaiser, Uschi Reich, Winka Wulff, and Burkhard von Schenk; Screenplay: Heinrich Breloer from the novel by Thomas Mann; Cinematography: Gernot Roll; Sound: Wolfgang Wirtz; Editing: Barbara von Weitershausen; Production Design: Goetz Weidner; Costume Design: Barbara Baum, and Sibyll Moebius; Music: Hans P. Stroeer

Cast: Armin Mueller-Stahl, Iris Berben, Jessica Schwartz, August Diehl, Mark Waschke, Raban Bieling, Léa Bosco, Maja Schöne, Nina Proll, Justus Von Dohnanyi, Martin Feifel, Alexander Fehling, Fedja van Huêt.

Color, 35mm-to-HD, widescreen, 151 minutes. In German with English subtitles.