9-18-09

“Writ in Water”— Bathed in Light: Campion Shows Us Keats in Bright Star

By Diane Sippl

How do we learn about poetry? Through

the verses themselves, written and spoken, or possibly through the personal

correspondence of the poets or their published discourse on the art? How do we come to understand the wrestling of

a poet’s conscience, or to enjoy the beauty of the words? In Bright

Star Jane Campion shows us how John Keats felt and lived and captured the timeless

in a moment, and how he was able to share his gift with those he loved.

Bright Star might look like a costume drama, which it is, with great success, especially given that its narrative point of view is that of a dress designer and seamstress; but this stunningly visual romance is also to be listened to, and therein lies the trick in Jane Campion’s inspiring feat as writer/director: how to bring the lofty, heady, piercing verse of one of the world’s youngest yet most prodigious poets to the light of the screen.

“(She is) beautiful, and elegant, graceful, silly, fashionable and strange… ignorant — monstrous in her behaviour flying out in all directions, calling people such names — that I was forced lately to make use of the term Minx— this is I think no(t) from any innate vice but from a penchant she has for acting stylishly. I am however tired of such style and shall decline any more of it — ”

John Keats in a letter to George Keats

December 16, 1818

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness; but still will keep

A bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet

breathing.

Therefore, on every morrow, are we wreathing

A flowery band to bind us to the earth,

Spite of despondence, of the human dearth

Of noble natures, of the gloomy days,

Of all the unhealthy and o’er-darkened ways

Made for our searching: yes, in spite of all,

Some shape of beauty moves away the pall

From our dark spirits…

From Endymion

In history, both John Keats and

Fanny Brawne each saw tuberculosis claim the lives of three in their families; each

of them lost a parent and at least one brother to the illness and each came of

age with a single mother. Mrs. Brawne’s

brother died in 1816, and Fanny had seen her own brother and sister die in infancy

as well. Both Fanny Brawne and John

Keats also lived with precarious financial legacies. While George Keats’ departure to

Bright Star takes us to twenty-seven months between late 1818 and early 1821, to Hampstead Heath, England — more precisely, to the parlors, kitchens, and chambers of three households, Elm Cottage (where the Brawnes lived), Well Walk (where Tom and John Keats lived), and Wentworth Place (where Charles Brown lived, soon to be joined by all the others but Tom) and the meadows and woods of their immediate environs. Within this space we share the conversations and strolls, needlework and musing, creations and misgivings of those who come to dwell under a common roof. Considering the life and work of someone like John Keats, who died at the age of twenty-five and in the two years prior had written some of the most esteemed poetry in the English language, Campion chooses the optimal depth of field for her focus. How many angels can dance on the head of a pin? In Keats’ imagination they are infinite, and Bright Star focuses on a few to suggest the many.

And dance, they do, both

literally and figuratively, in this strikingly sensual film that speaks with

direct simplicity counter-poised with Keats’ complex inner world. We join them for their socials where we meet

Keats’ circle — poets such as John Hamilton Reynolds and Leigh Hunt, painters

such as Charles Severn, and patrons such as Charles and Maria Dilke. Intellectual banter quickly yields to song in

a luscious choral recital in which Keats and Brown participate. Rehearsals of ballroom dancing, a Christmas

meal at the Brawnes where Keats orchestrates a Scottish tea ritual at the table

and flings himself into a jig, and impromptu waltzes in the garden are always a

measure of Keats’ physical joie de vivre. These scenes move the film forward brightly

beside abruptly static frames that arrest the eye in quiet contemplation and

still other sequences that are harrowing in their startling commotion.

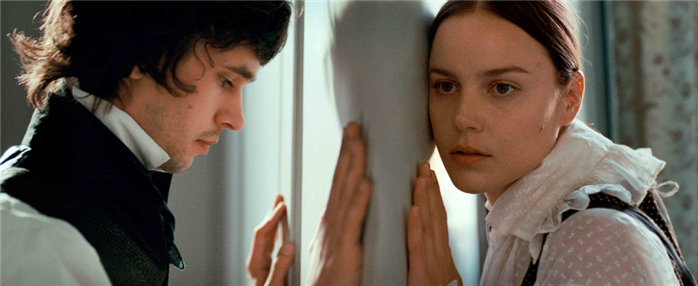

If one of the tasks of Bright Star is to put a face to the man — to give flesh, movement, and manner to someone who sought to enlist truth and beauty in serving his world through words — then both Fanny (Abbie Cornish) and Brown (Paul Schneider) are etched in such a way as to allow the poet to emerge before our eyes. Fanny flaunts her flair for fashion: “I originated the pleats on my dress. I’m the only one in Hampstead wearing a triple-digit mushroom collar.” Keats (Ben Whishaw) is a charming sparring mate: “Isn’t that another one over there?” he nods toward the mirror. He entices her into a walk to the pond. “I’ve explored all these parts, which are more in number than your eyelashes.” Brown can only mock Fanny’s obsession with flounces and her pretense with literature. Both Fanny and Brown are as testy as Keats, yet they dish up a sarcasm (Fanny’s witty and snide, Brown’s ostentatious and scowling) that the discreet and loyal poet knows how to avoid. His claim is more righteous, and his pluck can betray him. In response to one of Brown’s numerous taunts to Fanny, one coyly mixed with a crude flirtation, Keats blows up at Brown, “There is a holiness to the heart’s affections! Know you nothing of that? Believe me, it’s not pride!” Yet at that moment, both Brown and Fanny go stomping off from Keats, in opposite directions.

“What shocks the virtuous philosopher delights the chameleon Poet…. A Poet is the most unpoetical of anything in existence; because he has no identity — he is continually in for — and filling some other Body — the Sun, the Moon, the Sea and Men and Women who are creatures of impulse are poetical and have about them an unchangeable attribute — the poet has none....

John Keats in a letter to Richard Wodehouse

October 27, 1818

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain,

Before high piled books, in charactry

Hold like rich garners the full ripen’d grain;

When I behold upon the night’s starr’d face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance…

From “When I have fears that I may cease to be”

…sure a poet is a sage;

A humanist, physician to all men.

That I am none I feel, as vultures feel

They are no birds when eagles are abroad.

From “The Fall of Hyperion: A Dream”

CANTO I

Here we are reminded of the many occasions in which we see the poet adamantly chasing after his desire. High-spirited Miss Brawne is forever removing herself from dour Mr. Brown’s direct insults, and even from Mr. Keats’ ill-chosen or outspoken words. Self-conscious of the literary knowledge she lacks, Fanny often unconsciously flags it as an open wound, and thus an open gate through which Brown pounces on her, if only because she is his true rival for Keats’ attention and affection. Keats has a way of getting low with Fanny — on bended knee or sitting at her feet, begging forgiveness, pointing out his dire contradictions, cautioning her as to impossibilities.

He also has a way of teaching Fanny the delights of his profession. “I’m not clever with poetry,” she confesses. “Well, neither, it seems, am I,” he replies, acknowledging his critics. In looking at poetry as she might look at stitching, except that she has trouble “working it out,” she asks him for lessons to learn the craft. His reply:

“Poetic ‘craft’ is a carcass, a sham. If poetry does not come as naturally as leaves to a tree, then it’d better not come at all…” (And once he settles down — ) “A poem needs understanding through the senses. The point of diving into the lake is not immediately to swim to the shore; it’s to be in the lake, to luxuriate in the sensation of water. You do not ‘work the lake out’. It is an experience beyond thought. Poetry soothes and emboldens the soul to accept mystery.”

Toots (Edie Martin) is at once a foil for Fanny and her mouthpiece-in-miniature, speaking her elder sister’s alter-ego lines and frocked in fabric that could be remnants of Fanny’s dresses. Visiting Tom’s sickbed with Fanny, she utters that she wants to leave — it smells bad. “Shhhh!” gasps Fanny. “I’ll cut your hair in the night!” Shadowing Fanny as a younger chaperone, Toots’ voyeuristic role is at once a family duty and a touch of pure cinema. When she steals looks over her shoulder at Fanny and John as they stroll back from a kiss in the woods, the two lovers tease her with a game of “freeze.” We often see Toots lead Keats to Fanny (as when he returns from London toward their house, giggling at the little girl’s joy to see him) or lead Fanny to Keats (as when Toots, picking flowers, stumbles on him collapsed in the bushes). This is one little sprite who is clearly enamored with her big sister and who lives for the fringe benefits of the romance, among them an astonishing venture with butterflies that brings Keats’ fantasies directly down to earth.

“This living hand, now warm and capable”

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou would wish thine own heart dry of blood,

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calm’d. See, here it is —

I hold it towards you.

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

‘Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,—

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees,

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease...

From “Ode to a Nightingale”

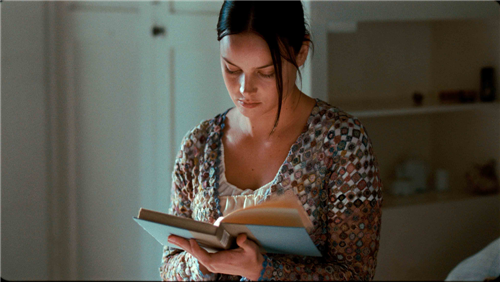

The film’s narrative might proceed through Fanny’s point of view, its intermittent scenes like stanzas in the epic ballad that is her love for Keats, and she may appear to us as the enigma who manages to shine for him in his deepest moments of grief, yet it is nonetheless the poet that Bright Star discloses. Fanny Brawne and Charles Brown are enthralling vehicles to the heart and soul of Keats — for youths who have not yet read Keats’ immortal verses, for avid fans who relish discovering the man in the poet, for long-time critics (such as those I overheard in the audience) who are “rusty” regarding his genius. Brown is continually flabbergasted at Keats’ imagination and his way with words: “Did these little hands do this?!” he remarks at their writer’s table as he takes the poet’s hand in his own. Unwittingly, he is acknowledging not only Keats’ literary gift but also his integrity as a human being.

The substance of the film — its rising joy and sinking sorrow — transpires precisely through Campion’s composition of scenes and dialogue that pulse with the music of Keats’ words, Fanny reciting lines from Endymion to Keats to win his admiration, or exchanging rounds of “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” with him after their two hearts have commingled, or speaking the lines of “Bright Star,” the sonnet Keats told her was “hers,” as she walks over the heath in the night. Pre-figured voluptuously in one of several keen high-angle shots — this one of Keats floating on a “cloud” of treetop blossoms — “Ode to a Nightingale” ultimately falls from the poet’s (Ben Whishaw’s) own lips as if posthumously, as the final credits roll on the screen. This recitation is not to be missed.

Before he died in 1821, Keats modestly

asked for the following to be inscribed on his gravestone, and it was: “Here

lies one whose name was writ in water.”

For all his mythic images and majestic turns of phrase, Keats wrote from

life, from his own excruciatingly inspired, numbered days and nights. Campion’s film deeply honors him by

meticulously recreating tangible evidence that he used his life to live up to

the vision of his verses. Beyond this —

which would be enough — her gift is to enrapture us with poetry and guide us in

grasping its rewards. Bright Star whets the appetite for an understanding

of ourselves and our world, the calling of true poetry and the art of cinema

alike.

“Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art”

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art —

Not in lone spendour hung aloft the night,

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors;

No — yet still stedfast, still unchangeable,

Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast,

To feel for ever its soft swell and fall,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever — or else swoon to death.

Bright Star

Director: Jane Campion; Producers: Jan Chapman and Caroline Hewitt; Screenplay: Jane Campion; Cinematography: Greig Fraser; Sound: John Midgley; Editing: Alexandre de Franceschi A.S.E.; Production and Costume Design: Janet Patterson; Music: Mark Bradshaw.

Cast: Abbie Cornish,

Ben Whishaw, Paul Schneider, Kerry Fox, Edie Martin, Thomas Brodie Sangster,

Antonia Campbell-Hughes, Claudie Blakley, Gerard Monaco, Samuel Roukin, Amanda Hale, Lucinda Raikis

Color, 35mm, 119 minutes. In English.