4-16-17

Half a Century of Ousmane Sembène’s Black Girl

By Diane Sippl

Ever since they left Thies, the women had not stopped singing. As soon as one group allowed the refrain to die, another picked it up, and new verses were born at the hazard of chance or inspiration, one word leading to another, each finding, in its turn, its rhythm and its place. No one was very sure any longer where the song began, or if it had an ending. It rolled out over its own length, like the movement of a serpent. It was as long as a life.

Ousmane Sembène, God’s Bits of Wood, 1960

There can be no development in Africa if women are left out of account.

Ousmane Sembène

Is there any young African who doesn’t long to go to France? Alas, the youngsters don’t know the difference between living in France and being a servant there. We come from neighboring villages in Upper Casamance, Diouna and me. There, we don’t say as you do that the light attracts moths; where I live in the Casamance country we say that it’s the darkness that drives the moths away.

Tive Correa in “The Promised Land,” Tribal Scars by Ousmane Sembène

Black Girl turned 50 last year, even though its protagonist died by her own hand in 1966 at the end of the film, as she did in life according to a brief report in a French newspaper at the time. But novelist/filmmaker Ousmane Sembène saw to it that she was resurrected, in nearly every work he created, and now, in her original good form, we can see her in a newly restored print as strikingly beautiful in Blu-ray and DVD as on the big theater screen.

Black Girl played the opening weekend at the UCLA Film and Television Archive’s deeply impressive and timely series, “In Transit: Refugees on Screen” (April 7 - May 5, www.cinema.ucl.edu) and can be purchased online from the Criterion Collection complete with short videos of the filmmaker and the actress as well as other supporting materials.

In 1975 Ousmane Sembène told a class of graduate students taking “Film and Social Change” in UCLA’s Department of Cinema-Television that Africa was the last continent to get cinema. In reference to black sub-Saharan Africa, he said, “Africans had to wait seventy-five years after the birth of cinema in the world to have an African making a film.” That was Sembène. Prior to Senegal's independence in 1960, blacks were effectively not allowed to hold a camera. (The same has been said by Carlton Moss of black filmmakers in Hollywood, such as himself, prior to World War II.) In the early 1960s Senegal had only seventy film theaters for a population of three and a half million, and their screens showed Africans through others' eyes. There were neither film processing laboratories nor editing facilities in the country. Yet in 1966 Sembène made Black Girl (La noire de…), black Africa’s first feature-length film.

In his day many a filmmaker – men, and later even women – shunned the label “feminist,” but Ousmane Sembène had no problem being known as such. You could bet that when a new work by Sembène came out, in literature or cinema, you would find at least one female protagonist and usually many. French by birth (in Senegal, 1927), he saw women as agents of social change in colonial and postcolonial Africa and therefore as vehicles for showing it and inspiring it through cinema. To act for Sembène meant not simply to play a role on the screen but to be a bigger player in history; thus many of his characters, and not just “extras,” were portrayed by lay actors who added a convincing layer of authenticity to his stories. That he shot on location in regions much of the world had never before seen – the Casamance district of Senegal where he was born, the streets of the capital in Dakar or its nearby villages in the countryside – and that he used indigenous music (if at all) – the xalam and the djembe – only added to the world’s new orientation to history and culture. Primarily, he brought a new point of view, a bold, singular voice and an adamant vision: that Africa could develop and advance without external manipulation and internal corruption, but equally important, that cinema could serve, rather than exploit, its viewers.

Sembène spent a good four decades pursuing this mission across genres. In the next generation, Cheick Oumar Sissoko from Mali and Djibril Diop Mambéty from Senegal, and then in the generation after that, Moussa Touré from Senegal and Abderrahmane Sissako from Mauritania, are but a few West African filmmakers who, one way or another, followed in Sembène’s tracks.

It’s one thing that he created a new cinematic language (Teshome Gabriel called it, variously, a “cinema of silence” and a “cinema of wax and gold”) but perhaps Sembène himself didn’t realize what a champion of women he was to become in the process. Women filmmakers were nearly unheard of and feminist cinema had yet to bloom at the time of Black Girl, even in Western countries.

Emitai (1972), Xala (1974), Ceddo (1977), Faat-Kiné (2001), Moolaadé (2004). Whether the women are resisting the French colonizers in World War II, polygamy and the black bourgeoisie in neocolonial Africa, priests and imams in the 18th century, patriarchal abuse in present-day Dakar, or female circumcision in village life today, Sembène shows that the society cannot progress without them. A rice-growing peasant, a middle-class city wife, a legendary princess, a single-mother entrepreneur, a bearer of “magical protection” for girls reaching puberty – these are but some of the characters in Sembène’s films, whether works of historical realism, allegory, or social satire. And it all began with the quiet lament of Black Girl, which already established a variety of motifs that would ribbon their way through Sembène’s oeuvre (for example, he makes a cameo appearance as a school teacher here). Cheick Oumar Sissoko’s ode to the power of women in Mali in Finzan, particularly the boys “vexing” the elders who hold court at a sacred tree invested with animist powers, echoes both Emitai and Xala but derives directly from the use of the mask in the ending of Black Girl. The stowaway in La Pirogue who is the lone female passenger on the boat in Moussa Touré’s film from Senegal may well be another homage (one of so many) to “the Father of African Cinema.”

Sembène himself, once a stowaway, was an émigré who, after his military service for the French, worked first at a car factory in Paris and then for a good decade on the docks of Marseilles, which inspired his first novel, The Black Docker. He wrote it following a workplace accident that crushed several of his vertebrae; while convalescing he became an avid reader and then a self-taught writer. Yet he managed to return to Dakar for the railway strike of 1947, which inspired another novel, God’s Bits of Wood (1960), in which he saluted the power of women. But it was a news report in the Nice Matin that gave Sembene the idea for a short story he would call, “The Promised Land,” which would appear in his collection, Tribal Scars. That story became the basis for Black Girl, his debut feature film.

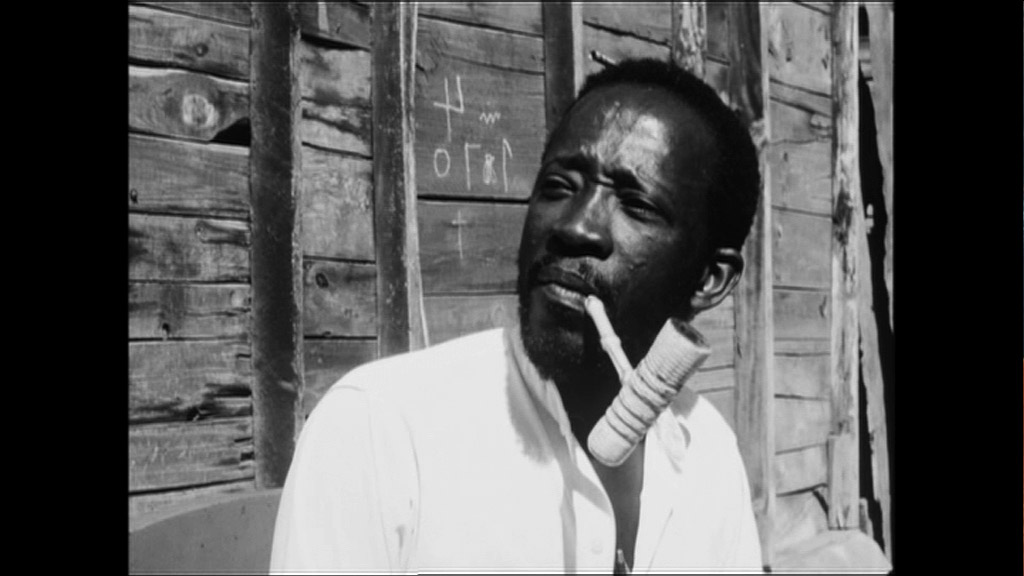

In the story a minor character, a town drunkard named Tive Correa, warns a young laundress for a wealthy French couple against traveling with them from Dakar to live in France. He is described as such:

Tive Correa was an old sailor who had returned from Europe after being away for twenty years. He had sailed away in the fullness of his youth, bursting with ambition, and had returned a wreck of a man. He had wanted all that life could offer, and had brought back nothing but an immoderate love of the bottle. He prophesied nothing but woe.

It’s this character (we could replace his liquor with a pipe) who carries the voice of the author, the prototype of the so-called “outcasts” in Sembène’s films – cripples or crazies or village fools – who pass on the wisdom (for those who can hear the news). Throughout his life Ousmane Sembène himself took on the role of the griot, the walking archive of the culture and its wisdom who tells the stories that stir the conscience of the people. With Black Girl he began to do it through cinema, and he even made a cameo appearance in one of the flashbacks his protagonist experiences in her stream-of-consciousness longing for Dakar. There, in a fleeting moment, we see him as a school master.

Sembène’s literature was written in French; Wolof (spoken in Senegal) was not yet a written language, so his script likewise was put down in French as he articulated his heroine’s emotions through internal monologues. Her voice-over is actually dubbed by another actress, since there was no synchronous sound recording equipment. Yet the relation between aural and visual language in the film becomes increasingly enticing. We come to inhabit the young woman’s psychic space within a verbal language she can hardly speak.

Cast in the lead role as Diouana, Mbissine Thérèse Diop was actually not yet an actress but a seamstress, and she sewed her own wardrobe for the film. Diouana’s costumes – fashionable and elegant dresses and accessories – catch the eye right off. When Josef von Sternberg dressed Marlene Dietrich in dichotomous black and white costumes for Blonde Venus, critics talked about their symbolic use in his melodrama. When Diouana’s costumes change in Black Girl, critics talk about how they become more “African” as the story goes on. In fact the black polka dots on a white background do get traded for a tropical pattern, but we can also see how the black and white scheme reflects the contradictions in Diouana’s life – as an émigré who is settled in neither culture, neither in France nor in Senegal, who has succumbed to false promises in the bargain, and who has neither voice nor listener where she now lives.

The film’s French title, La noire de…, evokes the colonial habit of not bothering to mention the country or to distinguish one colony from another in Africa (or on any continent, for that matter). The title also plays on the word “de” as meaning both “from,” as in a certain place, and “of,” as in belonging to her French “masters,” including her abusive mistress, the woman’s nonchalant and oblivious husband, and the presumptuous, self-entitled male party guest who kisses Diouana without her permission and without even “stealing a kiss” as can be conventional in “the movies.” He simply, arrogantly declares, “I’ve never kissed a Negress!” and exercises his postcolonial privilege and masculine prerogative accordingly. It’s a prelude to psychosexual anxiety in the household where Diouana lives and works.

Such behavior surely registers on the hostess, Diouana’s employer, who becomes more shrewish as she turns more defensive and jealous. She had hired Diouana as a nanny for her children in Dakar. When the family decided to return to France, the woman extended the employment to the new location, and Diouana was jubilant, but after her arrival the work role shifted to domestic servant and cook without ever so much as asking for Diouana’s consent. The woman becomes more brittle and repressive, and Diouana more isolated and depressed. They dwell on the Côte d'Azur, and the husband points out the view to Diouana – Nice, Cannes, St. Tropez, and of course, Antibes where they live. “Lovely country,” he sighs. Meanwhile his visitors remark, “…with independence, the natives have lost a natural quality,” as if the French would know what that was, or as if there even were such a thing. No matter that Diouana is at their side. They still carry on, “While Senghor’s there, we have nothing to worry about.”

But perhaps the self-righteous banter is the least of it. The fact is Diouana is isolated, not only exploited but alienated, uprooted, debased, humiliated. On her tragically stoic, stately body is inscribed the oppression of her era, as a migrant, as a woman, and as a servant of the global economy. Black Girl becomes more allegorical and lyrical as Diouana’s state waxes trancelike and dreamlike; a traditional mask she had purchased in Dakar and given to her employers comes alive with mythic meaning, as an African presence that both links her to her homeland and haunts her in her absence from it, just as it haunts her employers after her death. The husband returns the mask to Dakar, but it propels him away from Diouana’s family as if it were an animated god of vengeance or the embodiment of Diouana’s own comeuppance. In the last shot it looms large as held up to a boy’s face, a symbolic and elliptical ending that frames the film with the French title that opened it, La noire de… .

Black Girl (La noire de…)

Director: Ousmane Sembène; Producer: André Zwoboda; Screenplay: Ousmane Sembène; based on a novella by: Ousmane Sembène; Cinematographer: Christian Lacoste; Editor: André Gaudier.

Cast: Mbissine Thérèse Diop, Anne-Marie Jelinek, Robert Fontaine, Momar Nar Sene, Bernard Delbard, Nicole Donati, Raymond Lemery, Suzanne Lemery, Ibrahima Boy, Toto Bissainthe (voice-over of Diouana)

B/W, 65 min. In French and Wolof with English subtitles.

Get the DVD at: https://www.criterion.com/films/28849-black-girl