5-11-18

Offspring of Earth and Sun: Bashu, the Little Stranger

By Diane Sippl

Once when I was a child I was playing on a street corner, as children often do. Suddenly I saw a group of children coming toward me. I was startled by the way they had come together. I approached them and asked where they were going. They said they were going to school to gain knowledge. I asked, “What is knowledge?” They said, “We have no idea. This we will have to ask our teacher.” This they said to me and then left.

Shahab al-DinYahya Suhrawardi (1154-91), “Treatise on the Condition of Childhood”

in Hamid Dabashi, Masters & Masterpieces of Iranian Cinema

For the nobility of your own soul, if you ever run into Bahram Beizai, if you are walking, stand respectfully still until he passes; if you are standing, give the right of way to him; and if you are sitting, get up and give him your seat, for no one in Iranian cinema has more right to your highest respect and has earned your most sincere expression of humility than Bahram Beizai. Love and honor him, as he so richly deserves it. Some people in our old and enduring culture assume iconic significance, for reasons far beyond our crooked measures. Beizai is one of them.

Hamid Dabashi, Masters & Masterpieces of Iranian Cinema

The UCLA Celebration of Iranian Cinema will soon have spread over three decades of presentations by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, now showcasing recent and classic works, both theatrical and documentary features, from May 6th-19th at the Billy Wilder Theater at the Hammer Museum in Westwood. Thanks to funding by Farhang Foundation, the Archive’s partner and sponsor for the series, more than ever, directors, actors, and producers of the films are attending to speak with audiences in post-screening Q&A sessions, where it can also be the chance in a lifetime both to see the films and to meet the artists. The culmination of this year’s series on Saturday, May 19th at 7:30 is the screening of Bashu, the Little Stranger (1986). Calling it a “classic” almost strips this favorite of critics and crowds alike of its uniquely spellbinding power. With esteemed writer/director Bahram Beizai in attendance, the word-to-the-wise is “Stop—whatever you’re doing—Go, look, and listen.”

Depending upon your own familiarity with the culture(s) in Bashu, the Little Stranger, you may, in the beginning, feel that you, yourself, are the stranger. Perhaps that’s how Beizai would have it, but not just because those of us with Hollywood habits are used to reducing a movie to its plot points and action—even to its themes—which here display themselves easily enough as war and displacement, work and acceptance, family and community. Then those of us looking for hefty and relevant content can also find satisfaction in the issues of race, class, culture, and gender as presented in the film. With this much alone, Bashu makes for a compelling textbook in world studies of the 1980s and since then.

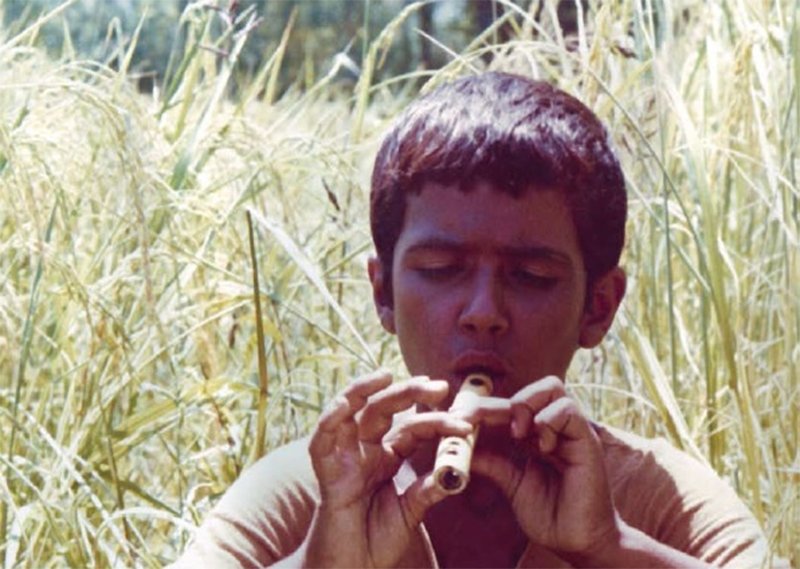

Yet, not just for this reason, I have taught Bashu in the classroom, on multiple and diverse campuses, over the years, and to my dismay, it escapes many a student. Granted, the film is subtitled (in fact, it doesn’t even use just Farsi, as might be expected); it is historical—actually, history-in-the-making, amidst the Iran-Iraq War that officially lasted nearly a decade; and its locations are not declared by inter-titles printed on the screen. Yet despite the lush settings and phenomenal actors, captivating performances of improvised music and traditional dance, and suspenseful editing that always brings a surprise, young people (not far removed in age from the characters) and sophisticates alike can be apathetic. Today when every country (even this one) hosts refugees from somewhere or everywhere, often from wars and physical devastation, I might like to explain my teaching predicament within the premises that Susan Sontag develops in Regarding the Pain of Others, her treatise on viewing images of war, leaving her pages for readers to discover on their own terms. Still, with (or because of) all the films that stream through our screens with the plight of refugees, I believe it is something else—the inventive genius of Beizai as an artist—that defies the lackadaisical minds of many just as it dazzles the imaginations of others.

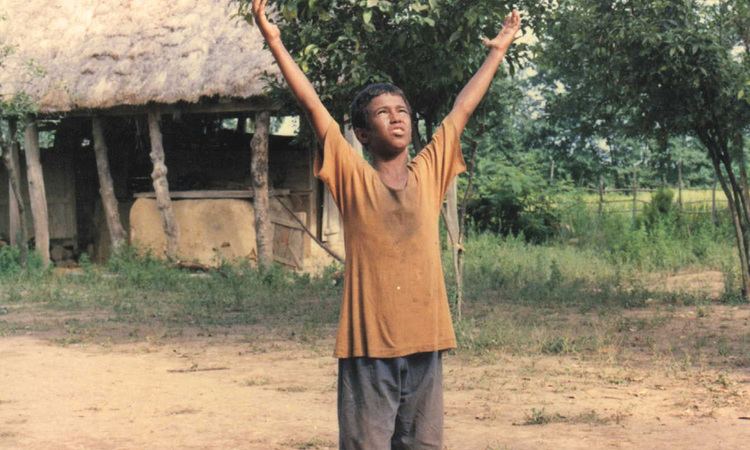

Drawing from a wellspring of philosophical/literary knowledge and experience writing and directing for the live stage, Beizai has cultivated his own language of sounds, images, and movement. Facing the encroaching era of computer-generated images in the 1980s, his creativity had as little to do with digital experiments as with conventional realism. Sound often plays a bigger role than words. The thunder of bombs in the South becomes the roar of a truck through mountain tunnels in the North and carries on as the blasts of local dynamite engineers, all the while the persistent rhythm delivers Bashu, asleep on the truck and unaware, from a desert of dates and palms to the spring green of rice paddies in a place he never knew or imagined. Yet his family follows him, his mother and sister veiled in black from head to toe—the girl we saw go up in flames and the woman who was sucked into the earth by an explosion—only to reappear time after time as he struggles to navigate life without them, God-knows-where.

We’re inside Bashu’s head and heart, and he is not the only one who sees these figures, but eventually also Nai, whose fields Bashu has invaded; at least she treats him as such, poking at him with a stick when her children bring her to him, as if he’s some kind of dark-skinned wild animal, a danger to her small, fair son and daughter. One of her first instincts is to “wash” Bashu “clean” with soap in the river. We find humor in the absurdity, but it’s not funny, unless we call nervous laughter a release of all that we ourselves have repressed. Nai herself is arresting, the way she shoots up from below to fill the screen, stares with alarm right at us, whipping her scarf across her face for protection. And she herself seems really to be an animal, conversing with the crows in their own language, shrieking to the wild boars, carrying on with the countryside fauna of the North, close to the Caspian Sea, it turns out. There in Mazandaran the dialect is Gilaki, but no matter, because for the longest time since the film opened, there has been no dialogue, and the first words come only when Nai feels the need to know who this “creature” is, a boy who, barely older than her own son, appears to have no home but hers. When they try spoken language, each one’s word (for “tomato”)—pomodore or tamata—carries the history of the colonial and commercial interests of its respective region. Gradually we discover that their exchange of new verbal language is reciprocal; Nai, who in fact possesses the mother wit of the ages and pluck to boot, is illiterate and relies on Bashu to write a letter to her absent husband. And Bashu humbles the terrorizing schoolboys of the village in an unforgettable sequence in which he desperately fights for acceptance by grabbing their textbook and reading aloud in the country’s elevated language of Arabic. They bond through a shared dance in a mesmerizing scene that once again requires no dialogue.

“We are all children of Iran,” Bashu recites. And we in the audience almost dare to include ourselves by this point, so engulfed are we by their sounds and images. We have become so immersed in their bizarre world of primeval instincts and rituals that when neighbors or relatives arrive from the village to curse Nai for housing Bashu, ignoring all of his labor on the farm Nai sustains and condemning him as a freak of nature, they embarrass us by displaying all the “isms” we conveniently forgot we ever held. We simply drop our jaws at the irony of Nai’s husband returning home across the rice paddies; missing an arm, he is as disfigured as the scarecrow Bashu built, and juxtaposed with it in the frame. At that moment, he, not the teenage Bashu, is the odd-man-out.

The way that Beizai turns our deepest myths inside out to glare at us through the film’s theatricality is astounding, for he allows us, as participants in the ritual that is cinema, not only to recognize our beliefs but also to construct them anew, in a visceral language dependent not on words but on feelings, on a tactile world of sounds and images that stem from a less mediated, more direct, and perhaps more universal code of shared values.

Bashu, the Little Stranger

Director: Bahram Beizai; Producer: Ali Reza Zarrin; Screenplay: Bahram Beizai; Cinematographer: Firooz Malekzadeh; Editor: Bahram Beizai; Production Design: Bahram Beizei, Iraj Raminfar, Costumes: Bahram Beizei, Iraj Raminfar.

Cast: Susan Taslimi, Parviz Poorhosseini, Adnan Afravian, Akbar Doodkar, Farokhlagha Hushmand.

Color, 35 mm, 120 min., in Gilaki and Arabic with English subtitles.