4-3-20

When Bacurau Descends:

The Past and the Future Look at Each Other in the Mirror

By Diane Sippl

A feast of fear and terror

Phantoms haunt the wake

Punching holes in the trunk of night, The woodpecker’s beak.

— Dirge chanted by Bacurauans

In research, sometimes very late at night, you are beset with fortuitous encounters, and depending on the topic and tone of your project at hand, such serendipity can be either laughably or frighteningly congruent with what you’re writing. When the undertaking is a discussion of the recent film, Bacurau—the name used by residents of Brazil’s hot and dry Northeast for an angry nocturnal bird—and you are in the process of reflecting on the meaning of the old Portuguese label for the region, “sertão” (i.e., “backcountry”), as you Google a map of Brazil, a startling paradox can jump onto your screen in the form of “breaking news”: it is not the rural poor in the hinterlands who are “infecting” the comfortable well-to-do of Rio’s Copacabana with the “ignorant backwardness” of their poverty and the diseases it breeds, but it’s the idle rich returning from resorts in Europe and the U.S. who are contaminating the country clubs, garden parties, estate weddings of Rio de Janeiro with the world’s deadly virus, and they may well be the first to fall. Yet you continue your research with the sure bet that soon enough, it could be the remote villagers of states like Pernambuco, descendants of runaway slaves from the sugar cane fields and cotton plantations, to bear the brunt of the pandemic as it mows them down in the absence of medical care.

And so the stage is set for the recent Brazilian film, Bacurau, as a woman anxiously makes a trip home to bring medicine to the inhabitants of this imaginary lone outpost even as its matriarch lies there dying. The unanimous participation of the community in Carmelita’s burial is staggering, and we get a taste of the ways in which ritual and necessity deeply bond the Bacurauans, young and old, black and white, indigenous or immigrant, male and female, and everyone happily in-between.

With the ubiquitous “social distancing” brought about by the coronavirus—not to mention the anonymity behind masks, the shuttering, quarantines, self-isolation, and actual deaths from the pandemic—all the while the buzz words “unity,” “togetherness,” and “connectedness” fly through the virtual air (along with nightly clap-fests with everything from bull horns to fireworks cheering front-line COVID-19 workers), what an uncanny moment for us to take stock of the notion of community! It’s certainly an idea we don’t so often see portrayed on the cinema screen these days, which is both shrinking and spreading by the minute to home streaming platforms far and wide as we go into hibernation.

And for that matter, what a moment to consider the concept of “global community,” an idea so against the grain of neoconservative campaigns around the world to shut down passage and relocation to safer ground—politically and economically, let alone medically—of peoples displaced by famine, war, and, lest we forget, foreign intervention. COVID-19 may be regarded as a force of nature, but there is a history to the social relations that host it, sometimes taught in school under the small headings of “neocolonialism” or “imperialism” when it doesn’t fit under the broader headings of “civilization” or “development” or is simply omitted altogether.

What many moviegoers may not know is that there is a history to these themes in cinema as well, not only in story content but also in film form, in structure and style, in the “language” of cinema that’s not the one spoken on the screen that has to be subtitled. It’s the one—really many—developed in leaps and bounds for more than a hundred years in places far from Hollywood, not just through film theory but also through experimentation and practice in nearly all the regions of the world. Narrative cinema sometimes bypasses movie stars and escapes genres or bends, blurs, and mixes them; the use of the camera and its relation to the mise en scène, the approach to editing, the use of music can all vary radically from one film culture to another, yet across Latin America, some home-grown styles have fused the tenets of key schools of thought—magical realism perhaps the most widely known, but also “imperfect cinema” and cinema novo, fundamental movements over half a century old.

As political economies everywhere submit to global contingency even if bizarre instances of “populism” sprout up as if they were urforms of folk wisdom, we also see more and more transcontinental inspiration among cineastes, co-productions among filmmakers across oceans and generations. Well-heeled festivals have something to do with it, offering grants, labs, and markets for promising artists and higher visibility through awards. It’s interesting that two films that shared the Jury Award at the 2019 Cannes International Film Festival—Les Miserables and Bacurau— both look like violent works of resistance stemming from historically displaced Africans; both anchor their narratives in the dispossessed forging their own communities, and both, amazingly, employ drones flying through the skies as key technologies of espionage and local warfare. But Les Miserables, staging a Parisian riot that one astute critic, Dennis Lim, noted evolves as “a paint-by-numbers policier,” is a far cry from Bacurau, a work so crammed with references and allusions and evocations that it has viewers inventing new hybrid labels for it all the while they make up their own minds about the mayhem, both on the screen and off.

A national culture is the whole body of efforts made by a people in the sphere of thought to describe, justify, and praise the action through which that people has created itself and keeps itself in existence. A national culture in underdeveloped countries should therefore take its place at the very heart of the struggle for freedom which these countries are carrying on.

Frantz Fanon

When one talks of cinema, one talks of American cinema. The influence of cinema is the influence of American cinema, which is the most aggressive and widespread aspect of American culture throughout the world.... For this reason, every discussion of cinema made outside Hollywood must begin with Hollywood.

Glauber Rocha

Brazilian films inevitably reflect the real social and political situation in Brazil. The lack of rigid racial segregation, the fact of a truly mestiço population, and the reality of political oppression of blacks all leave traces in the films. At the same time, the films do not reflect in an unmediated way; the films also inflect, refract, distort, caricature, allegorize. The notion that films reflect social reality should not lead to a naïve mimeticism.

Robert Stam

UFOs precipitating a violent Western shoot-out? A sci-fi survival thriller that’s a Sergio-Leone-style epic? A town that goes missing yet unleashes its mythic power on deadly invaders? Razor-sharp political filmmaking in the style of widescreen Panavision? How could one work of cinema be all of these? It’s possible, given the ways the seemingly contradictory claims above coincide with each other, though they only hint at the paradoxes in and around the captivating new film by Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles.

Kleber Mendonça Filho began his career as a film critic and journalist in Pernambuco, Brazil before he and his production designer, Juliano Dornelles, both from the capital of the state, Recife, turned to writing and directing Bacurau, a word that is said to derive from the language of the Tupi people, indigenous to Brazil from the Amazon region to the coast of the Northeast. Pronounced more like wakura’wa, it referred to a night bird that flies low with its beak open to catch insects, hence the later translation, “night jar” from the Portuguese word.

In a daring pastiche of popular film aesthetics and avant garde cinema practices, Bacurau’s camera “zooms” (with the help of CGI) from the outer cosmos to the one dirt road leading a water tanker to a secluded settlement. Along the way, coffins—rudimentary pine boxes—have spilled into the ditches from an overturned truck, and stray passersby are scooping them up, which stands to reason soon enough when the tanker arrives in Bacurau ridden with bullet holes, its contents pouring out into the dirt as if from so many spigots. The tone is sober, the desert drenched in myth and mystery. A feud is brewing between the townspeople, led by an unseen heroic “bandit”-rebel, Lunga, hiding out at the region’s dam, and a cocky bow-legged cowboy of a mayor everyone dodges with contempt. In suspended disbelief, we peel away the history of the town, but quietly and with some trepidation, because the motley crowd emerges as a core of citizens to be reckoned with, a brigade of solidarity bolstered by psychotropic seeds the members swallow as if simultaneously purging themselves of toxic outsiders.

The film takes its comic turn as a brothel-on-wheels rolls into town. The prostitutes shower outdoors, in front of God and everyone, and to conserve water, it then filters into a makeshift greenhouse set up in a one-time school bus. But there is no way to economize on the goods Tony, Jr., the mayor, delivers—food past its safety dates, street drugs, and so-called schoolbooks dropped from his dump-truck with his campaign posters smeared across its sides.

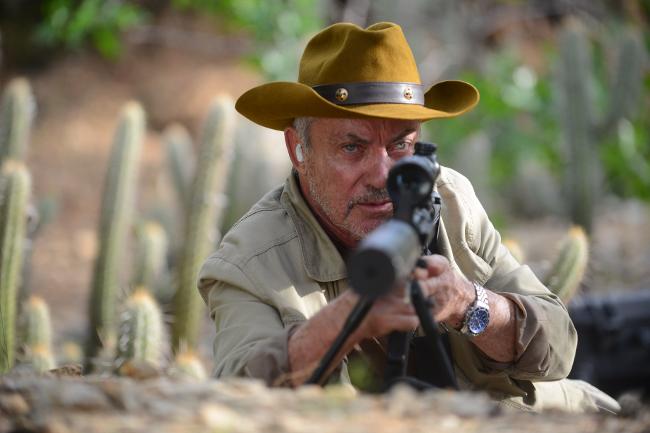

Then commences a sci-fi interlude of flying-saucer-like drone surveillance as local inhabitants are picked off like birds in a hunt by visiting tourists playing a “kill” game, first by Brazil’s own gallivanters from the urban South and then by a pack of hyper-enraged, demented pleasure-seekers from the imperialist North. Except for their quasi-futuristic technology (which also includes vintage-craft machine guns) and their distinctly low-brow mentalities, their vapid, arbitrary behavior recalls the surreal vignettes in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. The attackers are sex-crazed (“Let’s fuck!” caps off an exhilarating murder), psychologically deranged (a bad divorce produces a shopping-mall slayer), and violence-addicted (“I say we go in now and kill ‘em off”). They are an infighting clique of back-stabbers, to boot (“You Nazi! accuses one, with the proud response from the leader of the pack, a glassy-eyed Udo Kier, “...I’m more American than you are. Next time... don’t use such a cliché.”) Heads roll in Bacurau, literally, across the desert sand, not unlike the way they are rolled over the dirt for bocce in Sicily in the Tavianis’ film, Kaos from Pirandello; the gory impact is the same.

A lot is made of the trope (really a structured absence) of “disappearance” in the film: when the despised mayor rides into town with his loudspeaker campaign van, every last Bacurauan has disappeared behind closed doors, which happens again when the foreign invaders, his accomplices, arrive to attack the village. Like much in the film, it’s an inverted trope, a play on all the regimes “south of the border” (Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, El Salvador, to name a few) whose dictators “disappeared” any resisters. The fact is that in an outdoor school scene, the teacher finds that he can’t show the students where Bacurau is because it no longer exists in Google’s GPS on his iPad; it’s been wiped off the map. The grand irony comes when the trope gets flipped again. In post-screening Q&As, Udo Kier points out to audiences, “I don’t die in the end, I disappear.” The translation of the movie’s title, “night jar,” works well here, as the Bacarauans en masse gaze down—way down—upon their prey in the final scene.

The directors continually appropriate and re-contextualize stand-out lines, scenes, and motifs from Hollywood blockbusters and cult movies across genres and generations, playing them for irony as they upset the prevailing ways that people in their home, Brazil’s Northeast, are depicted. “I would emphasize the use of 1970s American Panavision C-series anamorphic prime lenses. In Bacurau, they give the North-East an industrial aspect that is uncommon in Brazilian cinema. The optical distortions of these particular lenses bring to mind a strain of American cinema that is very familiar but also quite foreign...” says Mendonça Filho. The eerie allusions and filmic quotations get mixed with the directors’ own memories and local lore passed down orally and even spoken today among the actors, most of them cast directly from the region and free to impart their ideas. In fact, in the Northeast, “bacurau” has appeared on bus signs as the name of the last bus home and evokes the feeling of “nighttime adventures” and “the mystery of something that is there, in the darkness, alive but unseen.”

Beyond these local legends, the film draws from a potpourri of North American pop cinema—Star Wars, Escape from New York, Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Die Hard, The Magnificent Seven, The Wild Bunch, and John Carpenter horror film music (Bacurau’s school is named after him!)—let alone war films from the ‘70s (Apocalypse Now is merely one). There are also spaghetti westerns such as Sergio Corbucci’s Companeros and “Death in Timbuktu,” the film-inside-a-film in Abderrahmane Sissako’s Bamako, where gunslinger Danny Glover shoots up women, children, and teachers, the symbolic prey of global capitalism. Still, Bacurau also owes a debt to Brazil’s own home-grown cinema novo movement of the 1960s.

This legacy, which permeates and arguably instigates Mendonça Filho and Dornelles’ film, is a matter of two forces—history and politics—both inside and outside of the films, both then and now. The “then” began in 1962-64 when a number of first-feature films emerged, in fact by directors from the Northeast (Barravento/The Turning Wind by Glauber Rocha from Bahia and Ganga Zumba by Carlos Diegues from Alagoas) and when others were made in the Northeast (Barren Lives/Vidas secas by Nelson Pereira Dos Santos, Black God, White Devil/Deus e o diabo na terra do sol by Glauber Rocha, and The Guns/Os fuzis by Ruy Guerra. These diverse filmic studies of slavery, poverty, banditry and myths, starvation, and political oppression were directly followed by the 1964 military coup that overthrew President Goulart’s democracy in Brazil. By 1968 a coup-within-a-coup ultimately drove some of these filmmakers into exile along with singer-songwriters such as Geraldo Vandré whose music is mixed into the soundtrack of Bacurau. Meanwhile a few, such as Nelson Pereira dos Santos, continued to make films under “internal” exile, such as How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (1970), employing the collaged perspectives and hybrid discourses of cinema novo as contemporary political allegory under the banner of Tropicalism, and Glauber Rocha completed Antonia das Mortes (1969), another uproarious epic of myth and legend, music and dance, referencing historic uprisings of Brazil’s Northeast.

While neorealism from Italy influenced Dos Santos early on, for example in Río 40 Degrees, and the French nouvelle vague inspired Ruy Guerra, there were others—Eisenstein and Brecht, for example—who also played a role in guiding a politics of cinema that would challenge the burgeoning commercial enterprise in Brazil’s film studios: new forms, styles, and also ways of approaching production meant that Black God, White Devil would prompt Ismael Xavier fifteen years later to write:

The film’s densely metaphorical style virtually pleads for allegorical interpretation even while its internal organization frustrates and defies the interpreter searching for a unifying ‘key’ or implicit ‘vision of the world’. And this resistance to interpretation is by no means incidental: it structures the film and constitutes its meaning.

How was it, exactly, that form and meaning could coalesce to subvert the given paradigm of the commercial filmmaking tradition of 124 years, and in the case of Bacurau, show a collective reminiscent of the quilombos (isolated settlements of escaped slaves in the Northeast) who thrived in resistance? In the epic style of Cinema-Scope photography with iconic scenes, the use of wide shots or extreme close-ups or split diopter shots that trade psychological depth for symbolic reference in the characters, a defiance of the shot/reverse shot suturing of the narrative and instead, long takes with the use of vintage dissolves or lateral wipes to change the sequence or even the tone or genre, with an oblique exposition of the situation that reveals it mostly through intermittent rituals (a funeral procession led by a guitar-playing griot, a spontaneous capoeira sequence in which John Carpenter’s “Night” fades into the sounds of bare feet on the ground), the film manages to build a mesmerizing suspense. The violence comes—we can be sure of it—with mystery as well, and parody—but no subtlety lost in its critique.

It’s a band of outsiders against a band of outsiders. Which is which? Identities are scrambled as the Brazilian “foragers” from Sao Paulo lord it over Northeasterners until these tourist-invaders from the South are picked off by the very foreigners who deployed them—after being mistaken as “ugly Americans” by Bacurauans, who in any event know exactly who they themselves are and what they stand for. In fact, one aspect of their identity remains impressively clear: that of the women, including the polymorphous, flamboyantly mythic Lunga (Silvero Pereira), part hero and part outlaw (the vestige of childhood stories in the popular culture of the cangaço), who half the time seems in a trance-like state, though s/he will save the day and put Bacurau back on the map. The exotic novelty of Lunga, a re-mixed throwback to such ‘50s films as The Bandit/O cangaciero by Lima Barreto, draws the spectator in as this iconic figure hides out in a dam-fortress over an empty reservoir. The women are key—the deceased “mother” of the collective , black as night, who still casts spells (water seeps out of her coffin in a hallucinatory mirage across the burial ground); her granddaughter Teresa (Bárbara Colen), who returns to grieve and save the health of her people; the town doctor and eccentric strong-arm Domingas (Sonia Braga), who dryly informs the arch-enemy, “I’ll feed your cock to the hens”; the prostitute, who draws empathy and comeuppance when she’s taken by the mayor; the potent Easter eggs of the town museum, symbolic of female fertility and also physically explosive, a stockpile of arms.

...it was happening and still happens: Brazil and the world are providing us with weekly “teasers” of the film.

Juliano Dornelles

Brazilians, among others, have often observed that history moves in waves, and while it took Bacurau’s filmmakers the good part of a decade to imagine, write, and shoot their film, once post-production was complete and it began its festival tour in competition at Cannes, they began to see it in the mirror in the form of real life. The museum in the film is a source of pride and joy (let alone armed defense) for Bacurauans, and it gets set on fire in the end. On September 3, 2018, long after Bacurau had been scripted, the National Museum of Brazil was destroyed by a fire that many say was part of a larger campaign of disinvestment aimed at the country’s history and culture. The museum, overseen by the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, held a vast trove of more than 20 million items—Latin America’s largest anthropology and natural history collection.

Not unrelated is the fact that in March, 2019 while mixing their completed film in France, the directors discovered that government agencies of environmental preservation were erasing grids within a protected Brazilian indigenous zone that had been deforested, so as not to include the information in official statistics; the reserves were simply deleted from the map. It’s an eerie feeling when you’ve just made a film in which the imaginary refuge of Bacurau gets “disappeared” from Google maps by foreign intruders in cooperation with the local coronel.

At the 2019 Cannes International Film Festival, Brazil saw more of its films accepted than any other country in the world did outside of France, Belgium, and the U.S., and a record-breaking 19 films from Brazil played at the Berlinale. These were among what is arguably the strongest crop of Brazilian films in the last half a century. They come from a labor force of 300,000 people employed in the production of cinema, a bigger sector of the society than those working in the pharmaceutical industry, but they may well be the last crop of film artists and technicians to be funded. In January, President Jair Bolsonaro dissolved Brazil’s Ministry of Culture, and since then he has frozen all funding for ANCINE, the national agency of film and television. These days he is seen out and about, unmasked, frequenting supermarkets and bakeries, posing for photographs with his fans. While the entourage that accompanied him to the U.S. is testing positive for the coronavirus, he’s “getting out to hug people.” Looking at both the past and the future in the mirror—call it now—it’s a mighty dark picture. But as this article gets posted, there are the chants, clapping, banging, cheering, and yes, even the civil disobedience of fireworks, to salute those fighting the virus at the front lines.

Filmic political imagination is a spark which can smolder in its audiences over long periods, which can carry across nations, continents, even class-experiences. It can serve to ignite debate, self-understanding, solidarity, within and on the edges of political movements. It offers a recolorization of the scenery, a pulse in the memory.

John D. H. Downing

Bacurau

Director: Kleber Mendonça Filho, Juliano Dornelles; Producer: Emilie Lesclaux, Saïd Ben Saïd, Michel Merkt; Screenplay: Kleber Mendonça Filho, Juliano Dornelles; Cinematographer: Pedro Sotero; Editor: Eduardo Serrano; Sound: Nicolas Hallet; Original Score: Mateus Alves and Tomaz Alves Souza; Production Design: Thales Junqueira; Costumes: Rita Azevedo.

Cast: Sonia Braga, Udo Kier, Bárbara Colen, Thomas Aquino, Silvero Pereira, Thardelly Lima, Rubens Santos, Wilson Rabelo, Carlos Francisco, Luciana Souza, Karine Teles, Antonio Saboia.

Color, Panavision DCP, 131 min., Portuguese with English subtitles