11-2-11

AFI FEST 2011: Surprises, Departures,

and Then Some…

Oslo, August 31st by Joachim Trier

The AFI FEST 2011 Presented by Audi offers ten days (November 3-10) of new films at the Mann’s Chinese and the Egyptian theaters, two of the most glamorous iconic settings of old Hollywood and also two of its best venues for viewing. With proper ticketing (at http://www.afi.com/afifest/), audiences can access the programs for free and see, beyond the star-studded galas each evening, the work of some of the most renowned auteurs of world cinema along with a few proclaimed new ones as well.

Except for Law of Desire, screened to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Pedro Almodóvar’s production company, his first film, and his attendance as guest Artistic Director of the festival this year, all other galas are primarily English-language films: Steve McQueen’s Shame (with Michael Fassbender and Carey Mulligan) and Simon Curtis’ My Week with Marilyn (with Michelle Williams and Kenneth Branagh), both from the UK, and even Roman Polanski’s French/German/Polish production, Carnage (with Jodie Foster, Kate Winslet, and John C. Riley). The Opening Night Gala is Clint Eastwood’s J. Edgar with Leonardo DiCaprio and Naomi Watts.

The Turin Horse by Bela Tarr

Befitting any film festival, especially one held smack in the center of Hollywood, are three astonishingly diverse works (for stark comparison with My Week with Marilyn) that showcase the daily motions of filmmakers and movie-making. In The Artist writer-director Michel Hazanavicius presents, sans dialogue, the black-and-white cinema of Hollywood’s silent era at the advent of “the talkies” in his playful and telling look back that highlights how sound both jarred and challenged viewing habits. The Day He Arrives adds to a chain of Hong Sang-soo’s light-hearted South Korean meditations on the life-of-the-artist-as-a-filmmaker, one who is either celebrated or not but is always walking and talking, smoking and drinking, dropping in at old haunts and haunted by dropped friends. This Is Not a Film, written and directed by Mojtaba Mirtahmasb and Jafar Panahi, is (ironically) not a film but more of a home video of the esteemed independent auteur of Iran, Jafar Panahi, whose films, from The White Balloon in 1995 to Offside (AFI FEST 2006) have both charmed and awakened audiences in Iran and abroad. A spotlight on the artist’s persistent imagination despite house arrest, passport denial, and a ban on filmmaking, this clever work delivers a day in the life of the cineaste fighting his oppression amidst the commotion of a human-size pet lizard inside the walls of his apartment and fireworks outside ushering in the New Year.

The actual “Spotlight Section” of the festival features a trilogy of works by American Joe Swanberg all made in 2011 — Silver Bullets, Art History, and The Zone — each nesting films within films. In the latter two of the three, Swanberg is virtually in front of the camera himself as he explores the relation between art and reality, sometimes with dire consequences.

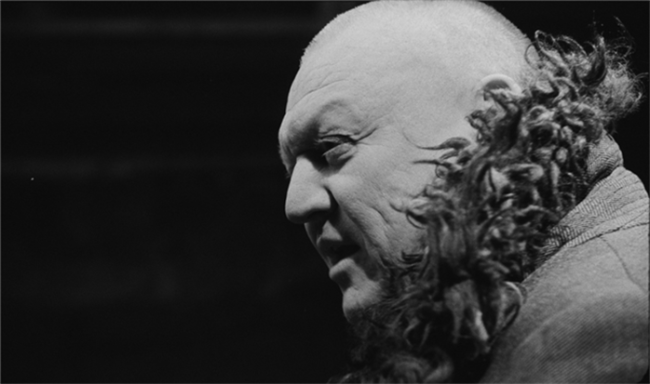

Faust by Alexander Sokurov

In three other sections of the program — “Special Screenings,” “World Cinema,” and “New Auteurs” — at least four recent films by powerhouse directors in terms of international reputation, career longevity, and artistic merit pack surprises for the viewer in their latest approaches to cinema. Prolific as these writer-directors are (some of whom produce or edit their own films as well), they have departed notably from their own canons as auteurs, sometimes with startling effect. Alexander Sokurov, Chantal Akerman, Wim Wenders, and the Dardenne brothers Jean-Pierre and Luc have all ventured out-of-bounds with regard to their own oeuvres, experimenting with aesthetic or technical leaps of faith that may land them wider audiences at the same time that they lose some of their long-time devotees.

Other highlights of the fest (not available for preview) promise to stick to the paths of their makers, pushing forward what they have always done best: Nuri Bilge Ceylan, his singular cinematography proffering a Chekhovian atmosphere and world view even in the steppes of Turkey in Once Upon a Time in Anatolia; Asghar Farhadi, his keen sense of ensemble acting to present human foibles, social contradictions, and moral vision in A Separation from Iran; and Hungarian Béla Tarr, his trance-like rhythms drenched in ominous light/shadow, sound, and texture in The Turin Horse. Meanwhile, in Oslo, August 31st, his second feature, Norwegian Joachim Trier appears solidly launched in his own new insignia of introspective characters who demand acting both intensely rigorous and spontaneously natural. Reviews by this author will follow upon screenings of the films.

Faust by Alexander Sokurov

First, the departures. Alexander Sokurov, who as early as 1996 was dwelling on the human body per se to show the profound emotions his esoteric film language could elicit through it in Mother and Son, has now created his own version of Goethe’s Faust for the screen, replete with a “Moneylender” devil incarnate in an unforgettably grotesque body revealed in a community bathing scene that is perhaps the most beautiful this side of Raphael in the history of art. Other sequences and set-pieces are equally astounding — mesmerizing and eye-closing at once — in a work of fantasy that is a cross between opera and painting, always cinematic with Bruno Delbonnel’s fluidly moving camera and Jörg Hauschild’s seamless editing but often distractingly, or at least distortedly so, with bizarre angles and tilted frames, seeming to suggest Faust’s deranged character point of view.

Producer Andrey Sigle’s original music might have been the perfect match for Sokurov’s last film, the boldly original Alexandra starring opera legend Galina Vishnevskaya investigating the life of Russian soldiers at the Chechen front, but it’s a mismatch in tone for this freakish, out-of-time “tall tale” with a dream-like resolution. Faust’s muted palette is often pastel-pretty compared to the sobering, de-saturated beiges and grays of earlier films, although Sokurov is here, as usual, at his best with a tactile atmosphere.

Faust by Alexander Sokurov

Yet Faust is sometimes too palpable. Moneylender’s bumpy body looks like a peeled pear whose surface has puckered into sagging mole hills from banki treatments gone bad. He’s as unsightly as the leper in the passing carriage or the warts on the penis of the cadaver as the film opens. And while Margarete’s frocks and cloaks are as exquisitely refined as any in Russian Ark, the gown and headdress of another local villager (the strangely familiar Hanna Schygulla) look like a costume for the Mad Hatter’s tea party. The film is less impressionistic than Sokurov’s other features: its first half is too talky and its second half too picaresque, so little emotional pull emanates from the hunger, greed, and lust that are said to reside in this gentle Faust, much as there is a sensual impact in his adventures, with continual reference to foul body odors. Finally, the doctor-scholar-philosopher who has “lost the meaning of life” is benignly insignificant beside Hitler, Lenin, and Hirohito as portrayed, respectively, in Moloch, Taurus and The Sun, the first three installments in Sokurov’s tetralogy on power and its abuses. As for Goethe, if his poetic sensibility is alive in this Faust, it has taken strange form.

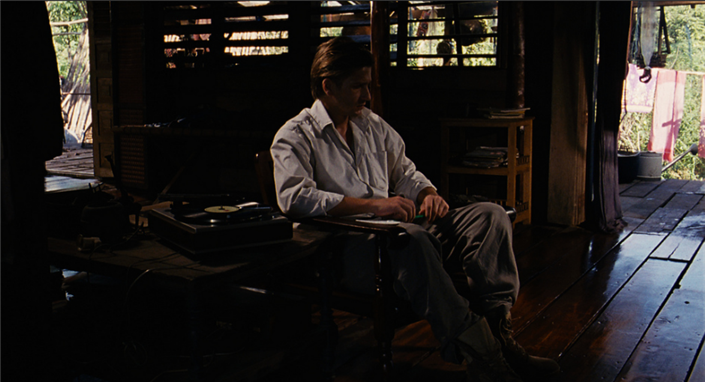

Almayer's Folly by Chantal Akerman

Quasi-experimentalist Chantal Akerman, whose 1975 film, Jeanne Dielman… tested the tenet of screen-time-as-real-time and whose work since then has set precedents for postmodernist probes of the relation between fiction and documentary, established herself in Brussels and then Paris as an independent making personal cinema. In the last two decades she has made both a well-reputed travelogue, From the East, and a literary adaptation, of Proust’s La Captive. Now she has written, directed, and co-produced Almayer’s Folly by freely adapting it from an 1895 novel by Joseph Conrad, his first and not his best. Akerman, as usual, endows it with her signature concerns and high style.

The first sequences already yield her trademark framing with head-on angles from a fixed camera in real time. A young woman swirls her body hypnotically (one could hardly call it dancing) on an outdoor stage along with several other amateur performers at an Asian honky-tonk while a male singer lip-syncs a routine to Dean Martin’s 1963 song, “Sway.” In a moment he is killed, and as the others run from the violence, the young woman is transfixed. Staring straight at the camera, motionless, she sings Mozart’s “Ave Verum Corpus,” a stunning tour-de-force by the actress, Aurora Marion, in her own voice. It’s a key element in Akerman’s version of the story. The film then flashes back to (as an inter-title on the screen informs) “somewhere else, before,” where this woman as a girl, Nina, is pursued through a long stretch of jungle along a river where her father, Almayer, lives until he finds the treasure he came to seek.

Almayer's Folly by Chantal Akerman

As in the novel, his real treasure is his daughter, whom he obsessively “adores” without imagining how to give her the everyday attention she craves and needs. Like many a Conradian colonialist, he lives in his dreams, lost, stuck, drowning himself in his passion as he treads a path into madness. Akerman transplants the setting from Borneo to Phnom Penh, and from the nineteenth century to some time not so far from today. Does it matter? Not if the only concern is the trance-like state of Almayer’s sinking existence.

But Akerman creates significant roles for the daughter, Nina, and her mother, a native from the region. While the narrative hinges on Nina’s half-caste status, playing it out as the fate of a mixed-breed tragic figure who has no place, Nina has her moments, verbal and physical stand-offs with her father. Her speech as she appeals to him arrives as if a monologue (for who could communicate with his forsaken, detached being?). Another time her words emerge as a voice-over, entering a larger pattern of repetitions with his voice-over reflections. In general the dialogue is minimal and stylized in its delivery. And interestingly, the filmmaker gives Nina’s mother, labeled “crazy” by Almayer who married her as part of a bargain for riches, a moment of narrative space in the film’s climax. Yet this is no Wide Sargasso Sea, at least not as Jean Rhys wrote the back-story to Jane Eyre in the “suffocating” jungles of the Caribbean. As Almayer reaches madness his wife waxes in rationality, but all too abruptly and simplistically.

Almayer's Folly by Chantal Akerman

What is more complex, and quite striking, is the lateral tracking shots through the jungle, moving endlessly from darkness to light and vice versa, and the ominous night scenes upon the moonless river. When Nina finally leaves upon that river, the fixed lens that follows her body into the shallow water and peers at her all the distance out to the large boat she boards begins to feel precisely like the father’s longing gaze, his wounded heart, his deranged mind. It’s a visceral shot, a long take — but nothing compared to the eight-minute-long close-up on Almayer at home, his shifting facial expressions as his loss takes its toll on him, with only three short phrases uttered, repeated somewhat, minutes apart.

Akerman employs Stanislas

Merhar’s acting to the utmost as Almayer, but gone is her keen sensitivity to

the patterns and textures of ordinary life.

While the long duration of her shot-sequences can have a kinesthetic impact

upon the spectator, imposing its own rhythms for viewing, the new relation that

comes with that impact is between the exoticism of nature — the encroaching

jungle, the eternal force of the river — and the mysticism of a pipe dream (in

this case, Almayer’s opium cloud), and not one of curiosity or understanding

between a filmgoer and a real girl. So

all the princes and rebels and traders, and for that matter, the knives or

bullets, feel more like window dressing in an adventure tale as Nina comes of

age in a place we know not where and a time we know not when….