11-9-12

A Royal Affair: The Thinking Woman’s Way in Denmark

By Diane Sippl

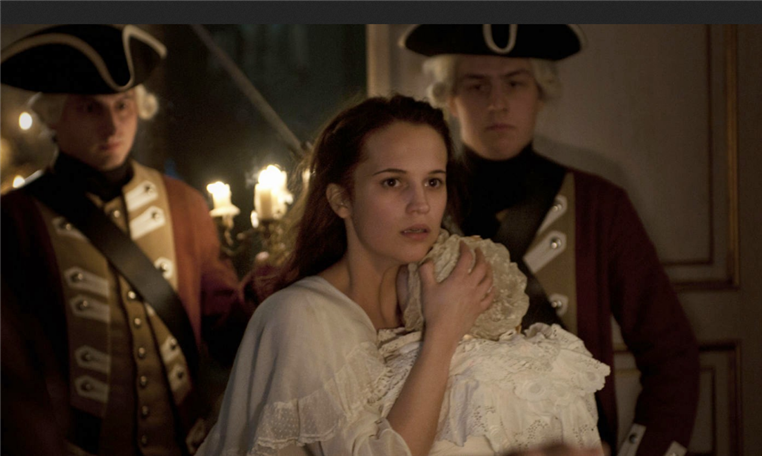

Queen Caroline Matilda (at her wedding banquet): And who are those people there?

Queen Caroline Matilda’s Lady-in-Waiting: Queen Dowager Juliane Marie and the Majesty’s half-brother. Neither she nor her son is popular with the people because the King doesn’t regard them as part of the family. The Danish people have always had a sixth sense about these things.

“Don’t steal my light…” a deranged king calmly threatens his new bride for her virtuoso palace performance of Bach upon his command. Yet what transpires that night in her private chambers shocks her out of submission to his highness’ authority, and it won’t be the last time. It’s one of the opening scenes of Nikolaj Arcel’s historical epic, A Royal Affair

Hot on the heels of its Audience

Award for World Cinema at the 2012 AFI FEST Presented by Audi and also its double

Silver Bear Awards at the Berlinale for Best Screenplay (Nikolaj Arcel and

Rasmus Heisterberg) and Best Actor (Mikkel Boe Følsgaard ) as well as its entry

from Denmark in the Oscar race for the year’s Best Foreign-Language Film, A Royal Affair looks like a real

crowd-pleaser. It’s been called a period

piece, a costume drama, a bodice-ripper, a romp in the castle, and more. Yet, why is it that this lush, stately,

bizarre concoction has so little to do with the eye candy and swashbuckling

adventures of other films of the genre — Bertrand Tavernier’s The Princess of Montpensier and Benoît

Jacquot’s Farewell My Queen, to name

just two recent works, along with Joe Wright’s Anna Karenina this season, in which Kitty is played by Alicia Vikander,

the leading lady of A Royal Affair? Curiously, this Danish drama has more in

common with Hollywood’s

version of the Swedish story of Queen Christina, that leading light played by

Greta Garbo at her height.

Who’s Courting Whom?

Based on the true story of three key players in history — Danish King Christian VII, Welsh Princess Caroline Matilda who becomes Christian’s wife and Denmark’s queen, and German Doctor Johann Friedrich Struensee who is recruited from a village in the Danish colony of Altona in Germany as Christian’s physician — A Royal Affair is, from the outset, never simply (or captivatingly, as it turns out) an international ménage à trois in the back rooms of the palace. On the contrary, it’s a strangely unpremeditated liaison that, despite itself and yet, amazingly, through itself, paves the way for a coup d’état — one unknowingly facilitated by the queen, unwittingly engineered by the doctor, and all but involuntarily enacted by the king, precisely against his own Council of Ministers.

And for a moment, what glory it brings! In 1769 in Copenhagen, Struensee’s anonymous freethinking ideas, banned as written documents and rejected by the country’s wigs at court, end up decreed by a king deemed a lunatic and signed into law by Struensee himself once he is appointed by Christian as the right-hand man in his cabinet of two. Smallpox inoculations for the people, orphanages for unwanted children, a reduction in peasants’ work hours by half, the abolition of corporal punishment of peasants, the outlaw of torture in the interrogation of prisoners and criminals, delimitations on the church’s influence on public matters, access to the university, a general license to publish, and the abolition of censorship — all of these acts of legislation are new to Denmark and make it a pioneer of the Enlightenment. And where will the money come from to implement such laws? Nobles who already earn income from their estates will give up their pensions.

What goes around comes around. Lust for the throne, for the customary favors of the court and the privileges that propriety ensures a closed circle of ministers, cloaks itself conveniently in an attack on the moral “disorder” at court, and those who hold that “the world was created in six days” seek to restore their place in the scheme of things. It is at this point that the romantic and sexual affairs at court are held in contempt by its enemies and manipulated against the royalty. And it is in this context that the film’s most moving scenes are written, staged, and acted.

Doctor Johann Friedrich Struensee: (Rousseau) has a point, that the way we have structured society makes it difficult for people to live their lives. Religion, marriage, anything that takes away our personal freedom…

Queen Caroline Matilda: Don’t have children, Struensee.

One simply must see the film to enjoy the innocence, beauty, and inspiration of its three central characters as they come together in the most socially and emotionally awkward of circumstances and yet manage to find themselves, each of them, in his or her proper calling, through each other. A rebellious 17-year-old who would rather be acting on the stage than sitting on his throne, an intellectually precocious 15-year-old who would rather be burying her nose in banned books than watching her debauched husband’s carousing, and a humble country doctor who would rather be liberating his patients than sending them to their death — these three frail, flawed, erring humans find strength and power in each other and launch no less than a revolution (one captured cinematically on the ballroom floor, by the way, as the camera follows two of these partners in a series of heady, slow-motion revolutions amidst a minuet). It’s a rather blessed way to discover “all that’s (not) rotten in the state of Denmark”… and all that the country might be.

“Light” is a telling motif in A Royal Affair. Yes, it sets the palette of the film’s frames, from pastel strolls in dappled gardens to weak winter shadows through a window in a lonely room. But it also means the limelight of the King that brings his happy moods, and for his Queen and their trusted confidant, the Enlightenment itself.

“They Have Their Exits and Their Entrances, and One Man in His Life Plays Many Parts”

Mads Mikkelsen in the role of Struensee discloses his character’s gift of seduction in one of his earliest scenes as he wins the king’s infinite trust with their exchange of lines from Shakespeare. Charming, sensitive, shrewd, even conniving, Mikkelsen displays the storehouse of emotions expected of his soulful heart and freethinking mind. Alicia Vikander as Queen Caroline Mathilda brings her youthful elegance to a complex woman who is centuries ahead of her time. The point of view on the story is hers, rightly and refreshingly so; the upshot of it all is the legacy for her children, who finish the job she has started after the film ends. Meanwhile onscreen, Vikander’s throaty voice-over narration adds a somber note to her dewy countenance that spawns a dimple when she smiles. Her teen body glows with the self-consciousness of Shakespeare’s Juliet, while her brain ticks away with her vision of work to be done.

Maybe the biggest surprise in this ingeniously written and superbly acted production is Mikkel Boe Følsgaard’s King Christian VII, a performance that never ceases to amaze. How he can hold us in suspense during moments of Christian’s uncanny mental clarity, when the King is utterly beside himself with the “brilliance” of his small victories, despite his outrageous indifference, mockery, effrontery and buffoonery, are the actor’s secret — in this case an actor playing a character who lives for acting, and not simply on the stage. Much is made of Christian’s spotlight, from the opening scene to the last, and it takes someone with the humility, vanity, and sheer imagination that Mikkel Boe Følsgaard has on tap to persuade us that Christian, as gullible and vulnerable as he is appalling, is entirely deserving of compassion.

In a post-screening discussion in Los Angeles, A Royal Affair director-writer Nikolaj Arcel and lead actress Alicia Vikander responded to the following questions:

In Denmark everyone knows the story of this famous trio; children grow up with it in their schoolbooks. But the rest of the world?

“Even in neighboring Scandinavian countries like Sweden, where I grew up, people don’t know about it,” responded Alicia Vikander. “Yet in Denmark there has been both an opera and a ballet about these events.”

“In 1954 we had a very bad German film made of it, but that version was not historically correct,” claimed writer-director Nikolaj Arcel. “For 35 years Danes have been trying to bring the story to the screen, but I think the budget kept it back — the expense of recreating all the period details.”

So in the end, what kind of high-level technology was used to present this very low-tech era for moviegoers today?

“Well we, also, had a limited budget,” explained Arcel, “so we used CGI (computer-generated images) for the castle, which doesn’t even exist any more as it was. For one shot we used 189 different versions to get it right!”

And what about the authenticity of the story? How long did it take to get that right?

“I spent a whole year for research alone, at the National Archives, reading witness accounts, books on the Enlightenment, especially Rousseau,” Arcel recounted. “There are so many stories of these characters, this moment in our history. We didn’t use any of the fiction works that have been published, or even the other books (at least 15) — only direct, primary sources.”

What dramatic license was taken?

“Mainly what was going on in the bedroom,” Arcel smiled. “There are no accounts of what was said behind closed doors, so we had to write that dialogue ourselves. But the rest is an accurate depiction of history. The only other difference is compression. In telling the story we had to condense time a bit and also leave out a few characters. We worked with three historians throughout the writing who were specialists on the topic, and they read many stages of the script and gave us feedback each time.”

I’ve read criticism that in reality, Caroline was neither an intellectual nor a political activist. Is that correct?

“That’s old-school thinking,” shrugged Arcel. “If you actually go and read her letters, it’s in them from the very beginning. Early on in her trip from England to Denmark, her political awareness already comes out. She was always an avid reader, and her acute social sensitivity was clear from what she read and also what she wrote in her letters.”

Was it difficult to write the role of the king, to discern exactly what accounted for Christian’s instability?

“For me that part was easy. From the beginning, I felt I knew that he was a child, someone who hadn’t grown up. And he didn’t want to be a king.”

You so craftily weave the theatre motif through the entire film in developing Christian’s character. Each of the scenes and lines is so cleverly inserted, with so much resonance. If I’m not mistaken, all the lines are from Shakespeare.

“Yes. And there is one scene from Ludwig Hohlberg, a great comedian.”

How is it that you came to cast a Swedish actress, Alicia Vikander, in the role of Queen Caroline Mathilda?

“I looked at many Danish actresses, but when I saw the regal way in which Alicia presented herself, I knew she

was just right. She’s a classically trained dancer with nine years at the Royal Swedish Ballet School before productions at the Stockholm Opera and the Gothenburg Opera,” Arcel explained. “With no previous command of the Danish language, she took eight weeks to learn it, just for the film.

“Yet if we were really to be accurate,” Akicia Vikander added, “they didn’t speak Danish at the court. They spoke French and German. But speaking Danish in my role did let me feel more like the outsider I was. And then we found the letters of Carolina, and that made the difference.”

Did wearing all those lavish costumes enable you to “feel” the role?

“The gowns were so tight,” reported Alicia Vikander, “that I literally couldn’t breathe, and I fainted for the first time in my life. Mikkel was there and kind of picked me up again.”

What about casting Mikkel Boe Følsgaard, though he had never acted in a single film yet, as King Christian VII?

“He actually hadn’t done any acting yet — he was in drama school (the Danish National School of Theatre),” added Arcel, “but I could immediately see his talent. He was very brave. He has guts.”

The film and its progressive spirit, on a collision course with those who “believe the world was created in six days,” seems so in-step with issues today, right down to those of the recent presidential election in the U.S.

“Yes,” replied Arcel. “I guess I would say that even the most right-wing parties in Denmark supported Obama, health care being the biggest issue.”

Has the film opened in Denmark yet?

“It opened in March in Denmark with much success, and it was also very well received in England and Australia. A Royal Affair has already sold to 70 countries, and it’s an honor to see it find distribution here.

A Royal Affair

Director: Nikolaj Arcel; Producers: Louise Vesth, Sisse Graum Jørgensen, Meta Foldager; Screenplay: Rasmus Heisterberg, Nikolaj Arcel; Cinematographer: Rasmus Videbaek; Editors: Mikkel E.G. Nielsen, Kasper Leick; Production Designer: Niels Sejer; Music: Gabriel Yared, Cyrille Aufort; Costume Designer: Manon Rasmussen.

Cast: Mads Mikkelsen, Alicia Vikander, Mikkel Boe Følsgaard, Trine Dyrholm, David Denick.

Color, 35mm, 138 min. In Danish with English subtitles.